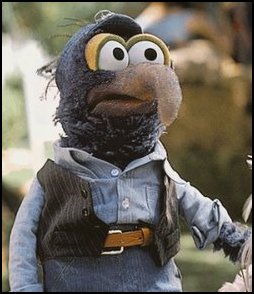

Gonzo: I’m going to Bombay, India, to become a movie star!

Fozzie Bear: You don’t go to Bombay to become a movie star. You go where we’re going: Hollywood!

Gonzo: Sure, if you want to do it the easy way!—The Muppet Movie ((Bombay seems like an odd choice for this joke. Wasn’t there a sizable movie industry in Bombay in the 1970s? Or am I confused?))

On twitter last month (I think it was last month; I find twitter-time difficult to reconcile with meatworld time), my friend Kip had an argument about art, effort, and transparency. Or that’s how I remember it, anyway; no doubt that’s all been filtered through my own biases.

On twitter last month (I think it was last month; I find twitter-time difficult to reconcile with meatworld time), my friend Kip had an argument about art, effort, and transparency. Or that’s how I remember it, anyway; no doubt that’s all been filtered through my own biases.

Many — most — cartoonists and writers work hard to make their storytelling as transparent and effortless for the reader as they can. This is where “transparency” comes in: the prose (or cartooning) is a clear glass through which the reader observes the story. The clearer the glass, the better.

But what about people who make stained glass windows?

The folks Kip was arguing with — also friends of mine — argued that making readers work hard is pretentious bullshit. Kip agreed, I think, that clarity can be a virtue, but that a creator could reasonably decide to focus on other virtues as well.

There was an elephant in the room, which I can’t recall if anyone mentioned: Kip is the author of City of Roses, a wonderful, web-serialized urban fantasy novel. Kip’s writing emphasizes character, mood, freedom for Kip to explore his own considerable quirkiness, subjective perceptions, and setting. But transparent prose really isn’t what Kip’s about. Kip’s prose could, I think, fairly be described as stained glass. Here, for example, is Kip’s self-described “elevator pitch” for City of Roses:

Violence; violence, and power, in the context of yet somebody else walking up to the groaning boards of fantasy’s eternal wedding feast, still laden with the cold meats from Tolkien’s funeral, and cheekily joining everyone who’s trying to send the whole thing smashing to the ground just to hear the noise all that crockery will make. —But! Also: genderfuck, hearts broken cleanly and otherwise, the City of Portland, Spenser, those moments in pop songs when the bass and all of the drums except maybe a handclap suddenly drop out of the bridge leaving you hanging from a slender aching thread of melody waiting almost dreading the moment when the beat comes back, and the occasional bit of swordplay.

On the one hand, as a reader I gravitate towards clear-as-glass writers (for many years Anne Tyler was my favorite novelist; nowadays I might say Connie Willis.). If I can’t effortlessly understand the prose in a novel, there’s a good chance I’ll put it down.

But (otherhandwise), sometimes what you work for is more rewarding than what’s offered on a platter. There are cartoonists and writers you slow down for; you have to be attentive. It takes a lot more effort to read Dave McKean’s Cages than to read Y: The Last Man. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed reading Y — a funny adventure with cliffhanger endings like clockwork at the end of every chapter — but if you read it at all, you’re appreciating it as much as you ever will. Putting more effort than that into reading it won’t bring any reward and is probably missing the point. In contrast, Cages is a thicker, richer and more nourishing meal. More like a bunch of meals, because it’s worth going back and rereading a bunch of times. If you pay attention, it’ll be worth it, because there’s so much there.

I’ve reread episodes of City of Roses a bunch of times. I’d highly recommend it (first chapter starts here). But it’s not “relax, turn your brain off, and be entertained” urban fantasy. It’s very rewarding, but readers have to put in a bit of work and pay attention. Which means — like Gonzo becoming a movie star — it’s going to have a hard time finding the readership it deserves.

Of course, writing this has made me think of my own work, which falls very much on the “transparent” side of the divide. But, to tell you the truth, I sometimes feel guilty about that. My favorite comics often aren’t as transparent, or as easy reading, as my own comics tend to be. For now, I’m enjoying what I’m doing too much to change it; but someday I hope to experiment with making some stained glass.

— Larry Niven

A few months ago I read House of Leaves, which is a wonderful and thoroughly opaque book, and a pretty good example of a case where obfuscation is a feature, not a bug.

Can’t remember where I heard this (National Public Radio’s Fresh Air?), but there’s some stock advice for professors advising students who aspire to become writers. If the student wants to become a writer because he “has something to say,” the professor should gently discourage him. If the student wants to become a writer because she likes to play with language, the professor should consider this matter more positively. So scores one for the stained glass lovers.

Perhaps apropos, a publisher is coming out with a new edition of Finnegan’s Wake, that famously opaque novel (?) from the famously opaque James Joyce. No need to rush to Amazon.com to reserve a copy; at $1000+ (or $300+ for the paperback), I don’t expect there’ll be a stampede.

I don’t know if this is a helpful way of thinking about either fiction or comics. One cannot make either form actually like “glass”; the conventions that readers are trained to ignore (or see as transparent) are historically and socially contingent, and presume a certain audience. Anyone who is expecting to have further reach, in time or space, must expect that “transparency” will ultimately disappear. The attempt to assign moral primacy to one convention or the other (and that’s what words like ‘pretentious’ are trying to do)… is irritating at best.

Your Muppet Movie quote: I always figured it was because he couldn’t speak the language; therefore, much harder to become a star there!

Just chiming in to say that Sailorman is right about “House of Leaves,” and it was immediately what I thought of when I read this article.

Personally, I think the “stained glass” approach and the transparency approach are each more appropriate for different contexts. In a political cartoon, you want clarity. There can be some meanings that are not at first apparent, but the main point needs to be hammered home. For a novel, which people have more patience with, I prefer a bit more stained glass. I do not, however, tend to like works that are almost completely stained glass and have almost no transparency, such as Danielewski’s followup to “House of Leaves,” called “Only Revolutions.”

@nobody.really – That was Maureen Corrigan in a Fresh Air review of a recent novel. I heard that and thought, “Really?!” Discourage people with something important to say? Or at least they feel is important? I wouldn’t want to be the one to judge what is important and not important to write about — at least, not until I have to lay my money down on a book — but Corrigan’s rule of thumb boils down to its own pretentious nonsense*. Every writer has something to say, whether it’s about a lived experience or the playfulness of language itself. An artistic statement, a critique of language, a juxtaposition of forms, a subversion of expectations — they all say something and rely upon the reader’s familiarity with forms, with literary history and with the nuances of language.

*Not referring to Mandolyn’s take on the “pretentiousness charge” — which I agree with. Often can be just another way of saying, “I don’t get it, so it must be snobby bullshit.” Granted, there are times when such a charge has merit. My point about Corrigan’s dictum is that it presents a simple-minded approach with an air of authority. Perhaps she grew weary of too many Grand Themes and Great American Novels — that is, exercises in “pretentiousness.” But if you can’t pretend, you can’t make good art.

BTW — nice write-up about Kip’s work. He must be all verklempft now.

I thought that House of Leaves was far more promising in the beginning than it was at the end; I hated the ending. Without giving anything away, I felt that it failed to, as Greg Egan would say, burn the motherhood statement. But that’s more about content than form. I suppose I was looking for too much by expecting to enjoy both aspects.

I wonder if you’re familiar with Douglas Hofstadter’s Le Ton Beau de Marot, which is all about the interplay of form and content in writing. (His earlier and more famous Gödel, Escher, Bach contains a lot of very dense content which is inextricably tied to its form; LTBdM has a lot about how and why this was done.) I know not everyone enjoys his writing style (I personally can’t get enough of it), but he’s amazing when it comes to ideas about self-reference, recursion and the balance between translation and what he calls “transculturation”.

Alix: sure, knowing Hindi would help one function in Bombay; but also, Gonzo’s hitchhiking.

Although Larry Niven’s a wingnut whose prose can be pretty awful, “use the simplest language possible” is good advice: I would say that Kant and Derrida used the simplest language possible to convey their ideas, and their language is difficult because of the intricacy of the thinking in it. But does that kind of argument really apply to literary genres? If you’re writing fiction or drama, the “something to say” and the “how it’s said” are not easily separable, even for writers whose prose is utterly flat.

First, what Mandolin said, with bells and an extremely cunning pair of trousers on.

And no insult or animosity or offense intended, but fuck a bunch of Larry Niven; it was a thick-headed short-sighted dim-witted patently untrue and worse unreflective statement just like that which set me off in the first place. (Note how easily, by the way, the concerns of others are set aside: “exotic or genderless pronouns,” he says, as part of his litany of stylistic nothings that are just not important enough; not worth “the simplest language possible.” —See Larry Niven. See Larry Niven obfuscate.)

—The thick-headed short-sighted dim-witted patently untrue and worse unreflective stimulus that provoked the series of disconnected, interlocking rants Amp so charitably refers to as “an argument” above was probably the Guardian’s “Ten rules for writing fiction,” which, at least, in all their self-contradictory glory, make it clear the only real rule is “Do what works and avoid what don’t.” —Gosh, thanks. —And while there’s some good humor and even a modicum of wisdom to be gleaned, there’s a lot more crap like Elmore Leonard’s Eleventh Commandment: “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

And I likes me some Elmore Leonard. (I’ve liked me some Larry Niven, too. But.)

The trouble with the prose-as-glass theory is that it supposes the prose, the words, are a thing that’s between you, the reader, and—what? What, exactly? What else is there, but the words? —Well, the thing you build in your head when you read, but that’s not something you see through the words, it’s something you build from the words; the words, and the stuff that’s already in your head that rings off and is suggested by and finds comity with those words, and that is why the intentional fallacy is a goddamn fallacy.

I don’t know why prose fiction alone has such an overwhelmingly popular dominant critical response of such misplaced faux-Zen asceticism. —No one says that to draw comics you should seek the limpid clarity of Don Heck; that if it looks like cartooning, you must redraw it. Everyone understands that Dogme 95 was just another genre of film, not the be-all and end-all One True Way to shoot movies qua movies. And as for music—well, yes, there’s always going to be some asshole who says Pulp’s appearance at Glastonbury in 1995 was the pinnacle and why the fuck has anyone bothered since and anyway what is up with hiphop that isn’t music there’s no goddamn melody, but people like that are rightly recognized as cranks and morons and at best they’re tolerated, not lionized, fêted, sought out and supplicated.

But prose has a thousand thousand voices out there all ready to cry out in unison that one must cut and cut and cut, excise, strip, remove and remove until nothing but clarity is left; clear clean glass ground smooth and featureless. Which is fine if you want to write a thriller that zips along its third-person limited-omniscient linear-past-tense track from set-piece to page-turning set-piece until you finally polish it off and put it down beside you on the beach towel and roll over to nap some more in the sun. But there are so many more things to be built with words! Machines that mimic thought, whole worlds that can’t be seen, great dizzying soaring ringing music, all of it from nothing more than one right word set after another. —What if what I want to do is “paint scenes with language”? Telling me not to do it unless I’m Margaret Atwood isn’t a lesson or an epigram or advice, it’s a goddamn dodge.

—Amp says I’d admit clarity’s a virtue; clarity isn’t the point, says I. You can make beautiful things with simple and clean and, yes, clear prose, prose that is easily and effortlessly read by them what has the correct reading protocols under their belts, but there’s nothing to see through it. It isn’t the clarity we prize, not really.

Though I must admit I’m amused that a cartoonist whose forte is such fecund and lurid and ribald grotesquerie should feel he’s ever let the stained-glass side down.

But oh hell here’s me ranting in a corner again, appearing to disagree quite loudly with a host who’s said such lovely things. All I can offer in my defense is yes, I’m verklempt. Also excitable. I do go on. And I’m yelling at the ground-glass ilk, who insist there’s only the one way to do it and that’s to throw out nine-tenths of your glorious toolkit because how else will you move units; Amp, of course, does nothing of the sort. No matter how churlishly I discount the very premise of his praise.

(And yes, there was a thriving movie industry in Bombay at the time, but who here knew about it? “Movie star” was a much smaller and more localized phenomenon in those days.)

I think Niven’s point on the subject of genderless pronouns is that, regardless of whether they’re a good idea, they’re going to confuse the reader and trip-up their reading.

Now, if that’s your goal, if you want the reader to feel their eyeballs turn into boiled eggs while they slog through your fiction, go for it. If you want them to go through the process of it feeling utterly alien at first and then possibly natural by the end, then do it. But don’t be surprised if the reader has trouble keeping up with what’s going on while this happens. Deciphering the language becomes a distraction from the underlying communication.

There are no genderless third-person singular pronouns in English other than perverting “they” (a practice I’m fond of). Introducing one means forcing your reader to learn a new language. Also, remember that Niven is a grumpy old semi-conservative (as much as one can be as a nerdy Californian) white SF author. When Niven was talking about genderless pronouns, he was probably referring to genderless aliens… he’s used the phrase “women of both genders” when referring to the Chirpsithra, an alien race he frequently used to say very little as bizarrely as possible.

Even Ursula LeGuin avoided genderless pronouns in Left Hand of Darkness, which is a book all about using a hermaphroditic race of humans to explore gender roles… although the author has, in hindsight, regretted the practice of referring to all the people of Winter as “him”. Personally, I think that would’ve made the final blow of the novel much more challenging to deliver – (spoiler) by the end of the book, the “perverted” gendered humans look strange, even to the gendered protagonist (and, by extension, the reader). If unnatural language had been intruding throughout the book to remind us that genderless people are alien to us, the conclusion would have been far more difficult to deliver.

This is something I noticed in House of Leaves – the final sections of each exploration (and the entire final exploration) are very clear. Still bizarrely laid out, but clear. That’s because this is when stuff is really happening. When it’s all really hitting the fan, the screaming din of footnotes and voices and blotches and realignment shuts up and lets the story take the driver’s seat.

Obviously, different strokes for different folks. Niven was writing for a specific section of SF fandom, and obviously his advice was intended for people writing for the same audience. In general, though, I think the advice is sound in most cases. Either explore the medium of your communication, or communicate. Don’t try to do both at the same time, or they will interfere with each other. There is a very short list of readers who won’t find this too frustrating to bear.

Also, I’m not Sailorman.

“Now, if that’s your goal, if you want the reader to feel their eyeballs turn into boiled eggs while they slog through your fiction, go for it. ”

[Snark removed by Mandolin.] Marge Piercy’s “Woman on the Edge of Time?” NOT a slog.

Moving away from gendered pronouns…

Plenty of fiction is playful with language *and* a pleasure to read, swiftly and easily, which is one thing this “stained glass” thing obscures, I think. I work enormously hard to make fancy or self-conscious prose *also* read fluidly and intuitively. Sometimes the emphasis is on one thing (e.g. “Memory of Wind” is intentionally difficult in some places, to mimic the effect of the character’s mind dissolving) and sometimes it’s on another (e.g. I just sent out a story with terse language and no metaphors to attempt to reproduce an angry, unself-reflective consciousness). The medium *is* the communication.

But, you know, it’s not a slog to read Charles Stross’s “Palimpsest,” which was occasionally weird with language in ways that were pleasurable. See also: poetry. And you know, genres worth of people who are both exploring their medium *and* communicating, such as the new narrative poets.

Bleargh.

Kip – too embroidered and fancy to read, sorry. Could you boil down your statement into a few very transparent sentences without all the grammar and whatnot?

Well.

If the strict goal of the text is to communicate certain information, then clarity is paramount. This is especially the case if there are theoretically-competing facts, from which the information must be distinguished. In this model, not only should one communicate all relevant facts, but one should avoid communicating irrelevant facts.

but that’s usually the domain of technical writing.

If the goal of the text is anything else, it’s pretty much fair game.

And I might also note that too LITTLE clarity can be equally annoying. I love Cormack McCarthy, but there have been times when I really wish he would use “he said,” if you know what i mean.

Stories are stories. Some are written as if they are spoken. Some are not. But they’re all stories.

I think the kernel of truth is this: if you’re going to choose to write something that will be deliberately difficult to read, you had better make sure that it’s worth it, either in terms of the message or in terms of the beauty of the language.

In terms of sci-fi/fantasy stuff, I’ve encountered far too many authors who seem to think of difficulty as an end in itself. I’m reminded, Mandolin, of the author for PodCastle who gloated on his livejournal about how much people would be confused by and hate his story. I’m not sure why that’s a reasonable goal, you know?

It’s not that difficulty is bad. Pointless difficulty, though is awful.

—Myca

I have really, genuinely, never encountered this.

He was reacting specifically to the people who post on the forum, who he thinks are stupid, and who he thinks are threatened by any suggestion of communism. IIRC, he’s a Marxist.

Sure, but as someone who is 1) not stupid, and 2) not threatened by suggestions of communism, his story blew … and it blew specifically because it was confusingly complex without payoff.

From reading through the forum discussion of the story, Marxism wasn’t mentioned once, and, “I had no idea what the hell was going on, and finishing the story was painful,” was mentioned more than once.

My point is that once you’re reacting with glee to the idea that your audience will dislike your story … well, you can justify that with, “they’re all stupid capitalists,” but maybe it’s a beard for, “I wrote an overly confusing story.”

—Myca

Yeah, maybe. But whether or not one particular demographic is confused by a story is not always a good metric. I mean, it can be. But it isn’t always.

The writer in question is well-regarded by a number of very smart people who presumably don’t find his work confusing, or don’t find it confusing in ways they consider important. So I think it’s troubling to dismiss it as “overly confusing”–overly confusing to who?

Robert: FIRE BAD. TREE PRETTY.

Foo: “Either explore the medium of your communication, or communicate. ” Which, I’m sorry, is a false dichotomy, but: if you force me to choose, I’ll quote Samuel Goldwyn: “You want to send a message? Call Western Union!” —To communicate is to explore the medium of communication; Christ, I’m writing sentences here that have never before been written in the history of language! Right here! In this message box!

—Back to Niven, and zie, and hi, and peh: Leaving aside the long and storied history SF already has with pronouns-of-alternate-gender, and the utter inability of talking about such things without having words for them, and the fact that SF is (among other things) in the business of coining neologisms (so pronouns are tiny and unutterably useful words and hard to swap out without twitching. Doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try)—look to the thing Niven said, not what maybe he meant to say:

Nothing to say. That’s what’s reserved for anything but “the simplest language possible.” The converse is blisteringly clear: those who do not use the simplest language possible, who innovate stylistically, who contort storylines (or discard them), who indulge in exotic pronouns or internal inconsistencies, who in fact do anything but take the established reading protocols as they’ve received them for the genre in which they have chosen to work and write to fit their measure, not one jot more or less—why, they have nothing to say. And so we can dismiss them, pfft!

Which is why I get all up in his face, fists balled and spittle-flecked.

(If that wasn’t what he meant, well, hell. He shoulda been more clear.)

The other reason I get all red in the cheek and shaky of voice is frustration; these sorts of discussions always come down to fucking grammar, and shibboleth gaily around adjectives and adverbs and whether you say “said” or not and how long your paragraphs ought to be and yes, grammar’s important, Christ, it’s all about the words and how you put them together, but grammar’s also the least of what it is we’re really talking about here with our pontificating about clarity of this or that or whatever.

It’s all about those damn reading protocols. (Why else do so many literary writers write such bad books with such beautiful prose when they try to write mystery or pornography or SF or criticism?) —What does your likely reader expect from your story? (How about the reader you’d rather be reaching?) —What can you legitimately expect to already be in their heads, to be called up by the words you put down? What do they already know and what will they see coming a mile away and what might they be surprised and shocked and delighted by, what will piss them off and what will they put up with? —This is the shit we need to be talking about, not how many exclamation points you get per chapter. Instead of asking a dozen writers how to write (what, you think they know?), the Guardian shoulda sent its readers off to tvtropes.org for some serious schooling instead.

i enjoyed some of the guardian rules. Others I didn’t enjoy. But yeah, i do think writers know how to write, and imparting that knowledge is useful, even when you disagree with them.

Hell, otherwise how would you know to bring TWO pencils on the plane? I <3 U, Margaret!

Oh, sure, I I’ve read (or listened to, actually) some of his other stuff and enjoyed it. I’m not making a statement about him as a writer. I’m saying that he correctly predicted that that particular story would be disliked as confusing and rather than finding it a problem, he was gleeful at the suggestion.

I just have a hard time not seeing a connection between that and the story actually being unenjoyably confusing for me.

I’m certainly not saying that people ought to dumb down their stuff. I loved House of Leaves … but, then, I also doubt that Mark Z. Danielewski was giggling to himself about how people would hate it, either.

—Myca

Indulge in hyperbole, and hyperbole will—hmm. Not quite certain how to finish that.

The wonderfully mundane advice along the lines of “take long walks” and “keep the tea warm” and “bring two pencils on the plane” was indeed all terribly useful and some of my favorite stuff on those lists. The rest either proved the writer knew and had a sense of humor about the impossibility of setting down such sage proscriptions in the time and space allotted, or did not know and had no such sense of humor. And I have this notoriously jerky knee…

You need to know what your readers are expecting; what they are used to; what the conventions are. And you can diverge from those expectations all you want–but you should intend to do so, and be prepared to deal with the effects of the divergence.

So you can write runon sentences, and you can refrain from using punctuation, and you can make a story as difficult-to-read as you want. But that doesn’t make runon sentences or lack if punctuation or confusing stories “good writing….” unless, that is, you choose to do those things deliberately. And even then, the benefits of making it hard for the reader need to be balanced by some commensurate improvement in meaning or interest or delight or what have you, or it’s not “good writing” insofar as you made a bad choice.

FIRE BAD. TREE PRETTY.

I was with you until you started using big words.

Sorry. I’d seen that argument expressed without humor recently. ;-)

(Well, if you want to start a tussle about whether writers can meaningfully articulate how to write…)

Some of my favorite writing is done by Neil Gaiman, who seems to go through his prose, shake 85% of the adjectives out, and wind up with this lean, cunning thing that pulls you through his stories like greyhounds after the mechanical rabbit.

Another piece of my favorite writing was “The Child Garden” by Geoff Ryman, which is one of the few SF/F stories I’ve ever read that manages to pull off the “casually mentioning technology/social conventions/cultural norms without explaining them until 100 pages later” thing without ever getting annoyingly coy. A neat trick given that it’s about, among other things, interstellar opera-singing polar bears.

Yet another is “Perdido Street Station” by China Mieville. If Neil’s work is greyhounds, China’s is flourless chocolate cake.

And I made it through “House of Leaves” and felt quite satisfied with myself for having done so, and quite impressed with Danielzewski for not having put me off at any point, though it seemed like he was trying rather hard to. Possibly I was so dogged about it, though, because I had been told over and over by a number of friends how unnerving it was, and I spent most of the book thinking “well maybe the part that will really make the hair go up on my arms is in this next chapter?”

Still haven’t made it through “Cages” though, despite having a really gorgeous hardback copy.

Exactly. Exactly. I wouldn’t have bothered with it if I hadn’t been so intrigued by the Tropes page and some of the discussions about it I’d seen.