I don’t believe in “natural” rights. Rights are a human institution; those rights that aren’t institutionalized by humans don’t exist. The only rights I, or any of us, have, are the rights that are recognized by the society in which we live.

So I don’t think — for example — that same-sex couples have a right to equal treatment under the law when it comes to marriage, in most US states. They don’t. They should, and I think they will in my lifetime. But we’re not there yet.

When people speak of having rights that aren’t recognized by society, I can’t agree. Where would rights like that come from? From God, I suppose, but I don’t believe in God. From nature, one could say, if one has never ever watched a nature show in one’s life. If you have a right to live, and the government shoots you anyway, and there are no consequences for those who shot you, then in what meaningful sense did the right to live ever exist?

Of course, it can be powerful to speak as if there are rights that exist outside of human institutions. It’s a sort of self-fulfilling prophesy; if you say “I have a right to blah, and that right is being denied to me,” then that use of the rights rhetoric makes it more likely that someday you will have the right to blah. I acknowledge that speaking of rights that way can be useful. But I don’t think it’s accurate.

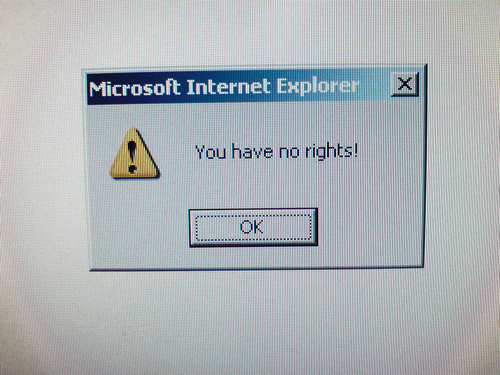

Illustration via TRG’s Flickr page.

When I first saw the picture, I thought this post would try to convince people to switch over to Linux.

If the only sense in which one can be said to have a right is that one makes a claim to such a right and that claim is recognized by others, then if I say that I have a right to something, I am saying that I claim such a right and hope that others will acknowledge that claim and act on it in support of my claimed right. If the law does not recognize my right, then it is less likely that others will recognize and act on my claim. To claim to have a right that is not generally acknowledged is to make a prescriptive statement rather than a descriptive statement.

The concept of natural rights is a good and important one — essentially, at its best, the idea that people have a fundamental right to be able to live their lives free of interference from others is a noble one, even if it can become impossibly utopian at its most rigid (although, to be fair, that’s true of almost every political system).

Are there literally natural rights, derived from a Just and Loving God? No. But the idea of natural rights doesn’t spring from God’s active interference in the world’s affairs. Rather, it’s the end result of the liberal philosophy; if one accepts the basic premise that each person should be able to live her life according to his or her ideals, so long as they don’t interfere with anyone else, then life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is the natural, obvious result of such a belief. And while it may not be literally true, framing basic human rights as the natural result of basic morality is a powerful thing. I shudder to think what would happen to free speech if we didn’t believe that the right to speak one’s mind is a fundamental right.

The problem with natural rights comes when they run up against society, which is by its very nature designed as a curb on pure individualism, no matter what the libertarians claim. You cited the right of gay and lesbian couples to marry, and that’s a great example. After all, one can argue strongly that nobody has the “right” to marriage, as marriage is a social construct. But this ignores the fact that the right to choose one’s mate has become a basic human right over the past century, at least in the west, and that marriage has become the default way in which two people declare that they have chosen to mate with each other. One can argue about whether marriage is the right vessel for that, but one can’t argue that it is the default one.

And so marriage becomes a basic good, like the right to speak one’s mind, subject only to laws regarding age, consanguinity, and number of partners — and gender. The last two are, of course, problematic, because they limit the right of someone to pursue happiness by choosing to declare that they and another willing person or persons wish to mate.

Now, one can take the position that all societal rules are arbitrary, and thus it doesn’t matter. But if one accepts the natural law framing, then one has to come up with a reason for the government and society to actively limit someone’s right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. One can find that in poly marriages — at least, the way they typically function now. But one struggles to find that in same-sex marriages, just as one struggles to find that in interracial marriages, another class of marriages that nobody has the “natural” right to.

Ultimately, while “natural rights” may not be the right term, it is the right concept. The idea that there are some basic rights that everyone is entitled to, rights that are fundamental to human life, the absence of which is directly injurious, is a powerful and, in my opinion, accurate one. No, it’s not granted by nature. And it’s not granted by God. It’s granted by the collective agreement of society — for this country was founded with that ideal baked in, and that ideal has, in fits and starts, worked throughout our nation’s history to slowly right the many wrongs we started with.

One of the reasons that I am so optimistic about the long-term struggle for marriage equality is that my fellow Americans ultimately always choose liberty. They may get it spectacularly wrong at first. They may fix things only grudgingly. They may fight for generations to avoid the consequences of the logic of liberty. But in the end, they give in, because ultimately, the American creed is that all are equal, and all have a natural right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It isn’t a natural law. It’s a societal law. Which makes it all the more powerful.

A very thoughtful post that does not advance the debate but does give it some additional dimensionality. And I’m with Mr. Fecke that Americans ultimately always choose liberty even if they do get it “spectacularly wrong” at first.

Unfortunately, according to your belief that “the only rights . . . are the rights that are recognized by the society in which we live,” minorities (people or beliefs) would never have any rights. “Majority rule” cannot be used as the basis for determining what is right or what is wrong. On the other hand, I agree that it is problematic for determining what the “natural” (or “universal”) rights are. If I were to list the rights that I think are natural, my list would obviously differ from lists drawn up by others. There will be fights about those, but that’s far different than letting it up to “majority rule.”

I also agree with you that “God” can never be looked on as a source of natural rights.

So I don’t think — for example — that same-sex couples have a right to equal treatment under the law when it comes to marriage, in most US states. They don’t. They should, and I think they will in my lifetime. But we’re not there yet.

“Should”. An interesting word to find in a post making this argument.

Why “should”?

In a natural rights framework, there’s an easy answer; Jeff touches on it, although he’s using natural rights as a convenient fiction that justifies a decent society and doesn’t actually believe in the concept on its own.

Without natural rights, why “should”? Why SHOULD there be a right, to anything?

Well, because you want it, of course. Nothing wrong with that – I want a BLT, myself!

But without some larger framing – without a natural right, or a right granted by God – there’s nothing other than desire. My desire to a BLT is outweighed by other people’s desire for the same; there are more of them and they are stronger, so they get the BLT and I get nothing. Sniff.

In your argument, you don’t have same sex marriage because a larger and stronger group says “no”. They want the BLT, so you don’t get it. Tough titties.

So how do we speak of “should”, in such a context, and have it mean anything more compelling than “but I really wanted it”?

If a right falls down in the woods and nobody complains about it, did it exist?

And yes, I agree that this shouting about “innate” or “natural” rights is absurd. It’s puddle-deep moral philosophy.

There are no natural rights. Zero. Nada. Nil. The only rights that exist are the ones that we, as a society, decide to protect.

Is there an absolute concept of right-and-wrong? Yes, I think there is – one that flows from how our actions help and harm other people. But I don’t think it falls along the arbitrary lines in the sand we call “rights”. Rights are a convenience concept for laws, because we can’t trust the lawmakers. They are a necessary device for a world of imperfect humans with incomplete knowledge. There are things that are wrong and in a fully just system would be punished… but we can’t make them illegal because it is too dangerous to let lawmakers wield that kind of power.

The Westboro baptist Church’s right to freedom of speech is protected not because we really believe that it’s okay that they do what they do, but because we don’t trust anybody with the power to stop them.

interesting discussion on where policy and metaphysics meet. i agree, some constructions of natural rights, like say “we hold these rights to be self-evident” are circular logic, attempts to avoid looking into the abyss where Nietzsche philosophised. justifying what is clearly a social construct in a world without god is not easy.

but i don’t think all constructions of natural rights are so circular or punt to theology. Locke saw natural ringts as more in tune with man’s nature, not unlike others saw communism as out of tune. he like Kant and later rand tried to derive rights from reason alone. its still messy, a priori justifications being hard to detach from the circulr. interstingly, the philosophical insight that there is no a priori principles is itself an a priori principle.

This position doesn’t follow from your earlier philosophical musings, because at this point we’ve already accepted the philosophical foundation of rights. The Bill of Rights isn’t just a hodgepodge of enumerated good things. in fact the document explicitly states that the rights don’t have to be enumerated.

That’s because the doc is protecting us from freedom from the initiation of force from government and ensuring these freedoms are equally protected, unless the state has some compelling interest, like national security. the right to gay marriage is already in the document because to say its not is philosophically inconsistent with the reasoning behind the bill or rights.

Rights seem to be a handy model for thinking about features in a society which should be hard to change. Can you suggest an alternative model?

I’m undecided on the concept of ‘natural rights’, but I do think that there’s a difference between “I have the legal ability to do X” and “I ought to have the legal ability to do X,” and I that the concept of ‘rights’ often encompasses the latter.

Additionally, if ‘rights’ just means ‘the stuff the government lets you do’, then why do we have the concept of ‘infringing on human rights’? Should that only apply in situations where the government is violating rights it has previously granted (like, say, freedom of speech in the USA) and not in situations where the government hasn’t granted those rights at all (like freedom of speech in the USSR)?

—Myca

“So I don’t think — for example — that same-sex couples have a right to equal treatment under the law when it comes to marriage, in most US states. They don’t. They should, and I think they will in my lifetime. But we’re not there yet.”

Like Robert, I don’t understand how you get the ‘should’ there without a concept of something like natural rights. On what basis do you judge that society should or shouldn’t do something if you aren’t comparing it to some ‘right’ or ‘value’ that is outside the society. If rights and values are just whatever the society does, should and shouldn’t doesn’t really come into the discussion.

I also think Myca formed a related question very well. To further that, even if rights were previously recognized why should that matter/help.

I think in the american context, both strict constructionists and living constitutionalists would agree that the bill of rights was never intended to be simply the stuff govt allows you to do. alexnder hamitlton explicitly stated that the bill of rights should not be interpreted to mean these are the only rights, ie that unenumerated rights would not be protected.

furthermore, the 10th ammendment makes explicit the notion that the federal government is limited only to the powers granted in the Constitution. so to say the people only have freedoms listed in the bill or f rights, is to flip the document on its head.

A moral or ethical code does not need to depend on a concept anything like natural rights. There are many ways to get there.

I think there are 4 general philosophical positions here:

1. absolutism/a priori : god grants these rights/ we hold these truths to be self-evident

2. rationalism: locke, kant, etc: reason dictates we should have these rights…theses rights are part of human nature.

3. utilitarianism to social constriction: all rights are a product of humanity but they have demonstrative utility (greatest good for greatest amount of people)

4. nietzsche: there is ultimately no basis, rational or otherwise, for any of this but if you want rights you simply must assert them as a will to power.

I think this is a debate you and I had 25 years ago, and as I recall the 80s both our positions have changed a great deal. Middle age and hardening arteries does that…

I agree, no one has any “inalienable right” that anyone else is under any obligation to respect 100% across the board. We have socially constructed “rights” that we give each other by mutual consent, but that’s a social construct. If someone says “I have a right to ______,” it’s like trying to claim a coupon in a store, they can choose to honor it or not.

I’ve developed into a fairly religious person in a rather eccentric “one man denomination” way. I believe God INTENDED for us to create rules for respect and mutual consideration for each other and abide by them. But I haven’t seen any pillars of fire from on high enforcing those.

We’re on our own to create the just, kind and loving society we were intended to live in, and then defend it from the barbarians that would cheerfully kill us for being different. (If anyone wishes to know how I think, watch the movie BILLY JACK followed by DAWN OF THE DEAD, and it’ll be just like being a house guest of mine for a weekend. Oh, and drink lots of beer, it helps when you’re around me for prolonged periods)

It’s why if I had ever managed to have kids of my own, I’d have given them both religious training and firearms training. One to show them how to treat others, the other to defend themselves from people who disagree on how people SHOULD treat each other. I may be the only left wing “bible and bullets” person most people will ever meet.

I might have also gotten them taught krav maga, just to be sure.

Whatever your issue folks, GLBT legal rights, fat acceptance, poverty rights, religious freedom/freedom FROM religion, what have you, just trust me. Charles Xavier is not your role model, Magneto is.

Actually, you’ve just summed up one of the best arguments for God. :)

Because I want it to.

I am a citizen of a government which presumably has as one of its principles the attempt to attain the goals of its citizens–even if those goals involve significantly changing the way that the government itself works (IOW, there is no inherent prohibition against changing the process entirely.) Another one of the government goals is presumably to objectively benefit its populace, which I also think would help for many of by preferences. I don’t have many goals which I believe to be anti-US or anti-government.

Obviously, my desire is also subject to the opposing desires of other parties. That is why the government doesn’t match my personal ideal. But I assure you that I don’t need natural rights to believe that I would like gay marriage, say; nor do need natural rights to believe that the government should adopt my position. All I need to do is to believe that I’m right.

Have to agree with Bob on this one: words like ‘should’ or ‘ought’ – in a categorical rather then a hypothetical sense – can receive no validation from feelings, desires or any other such phenomenona. Phenomena are, after all, facts of the natural world and cannot be made criteria of value (why should a natural-world fact be the criterion of other natural-world facts – what priority can be established between them without a reference to values beyond them?) You need something outside the natural world, something noumenal or at least numinal – Plato’s Good/Beauty or a God who is righteousness – as such a criterion. Without them you cannot say, ‘you ought to do this’, only, ‘various facts of biology, psychology and society induce to me to want you to do this’ – a statement which does not even pretend to moral force.

since we’re discussing first principles, can someone please explain to me what happened before the big bang. I mean, if nothing happened then how can something come out of nothing? if something did happen then the big bang isn’t the beginning, is it?

i don’t get it.

Why not? Life doesn’t need to mean anything for it to be or for it to be worthwhile. Any priority can be established between “natural-word facts” that we desire. Our desires are not beyond the “natural-world,” they’re part of the “natural-world.”

Comment # 18 is just the common argument for the supernatural that has no effect upon those who find no need for the supernatural. I must admit, however, that that argument seems to resonate for those who find a need for the supernatural.

I agree that there are no rights but what we choose, but I also believe there are natural consequences to every action that we do not choose. The actions we collectively demand and the actions we collectively forbid will always be based upon a desire to ensure beneficial natural consequences occur and to ensure harmful natural consequences do not occur.

The oldest and most pervasive rights and obligations in any culture will be those that were most effective at ensuring the continuation of those practicing them. The newest and least pervasive rights and obligations will be those that were least effective.

In the sense that some actions naturally move a culture toward extinction and some actions naturally move a culture toward continuation, some actions might be referred to as natural rights.

So how do these arguments influence the political process in a country that was founded on the very principles you deny exist (or consider fallacious) and that are believed in by the majority of the electorate?

As a reminder, from the Declaration of Independence (which has no legal force but explains the philosophy we were founded on):

My emphasis, obviously. The point being that your collective assertions regarding natural rights and their origins flies directly in the face of this – and while you all certainly have a right to believe as you do (thank God for the First Amendment) most people in the U.S. accept the above formulation and base their understanding of what’s a right and what isn’t at least in part accordingly.

i think ironically, for much of the left, there’s no point challenging the sweeping absolutist, a-priori, theological foundation of rights when it comes to Gay rights. this formulation only help the cause, since its plain meaning puts severe restrictions on government actions.

undermining the philosophical foundations of rights (usually by revealing their oppressive historical context–only protecting white males–and thus undermining their legitimacy by pointing out, like the founders did with “divine right of kings”, that they are actually a product of power relations not natural law,–as critical legal studies does) is helpful when the left is trying to go against the grain of limited govt: like regulating economic behaviour, taking private property, outlawing porn, establish hate speech laws. anti-discrimination laws, allowing the govt to take race into consideration, gun control, expanding govt beyond the powers enumerated, etc.

You’re wrong. Hilariously wrong. My assertions regarding “natural rights and their origins” are in no way contradicted by folks who believe those rights were imbued by the supernatural.

My nephews believe that their presents come from Santa. This in no way makes my assertion that their parents bought those gifts “fly directly in the face” of the facts. My nephews’ beliefs do not reflect the reality. Neither does that line from the Declaration of Independence.

Just because the author of the Declaration of Independence believed in the supernatural does not make our rights come from the supernatural. That’s a ridiculous assertion to make.

Jake, I think you’re misreading him.

I’m no fan of the supernatural, but I think he’s not asserting the D of I as proof of supernatural effect, he’s asserting it as proof of what the framers believed to underlie the rights enshrined in the Constitution. in other words, I think he is saying that it is appropriate to include natural rights discourse when discussing U.S. constitutional rights, because the Framers’ philosophy so dictates.

At least, I think so.

The Framers, as well as many millions of Americans today.

Sailorman,

But that has no bearing on whether or not natural rights exist. I thought we were discussing the existence of natural rights, not whether or not people believe in them. I also took exception to his words because they imply that somebody said that the framers didn’t believe in natural rights given by the supernatural. I can’t see how his “flies in the face” comment is related otherwise.

The framers first principles don’t really matter in this case. Whether they believe the rights we agree on come from some undetectable creator or they believe that the rights we agree on come from their cat doesn’t make a difference when it comes to US Constitutional rights. At least I can’t see how it does.

that famous line of the Dec of Ind was just a philosophical punt. what the framers were saying is ” look, we don’t have the time on our hands like Immanuel Kant does to to write a huge philosophical treatise, so we’re just going to start from this somewhat shallow premise but dress it up in fancy language so it sounds all profound and shit.”

the reference to god, which has resulted in many a conservative orgasm, was just a little deism: there is a God but he’s not too involved and you know his truth by using reason and observation of the natural world and natural world only.

from this premise we can derive s system of natural rights, which, imo, includes the right to same sex marriage b/c the entire system depends on govt not being able to treat their citizens differently under the law for specious reasons. thats why slavery almost undermined our entire regime.

the apt named loving precedent was a logical interpretation of the 14th and it naturally should apply to gays like the 1st naturally applies to the internet.

where the hell is PG? don’t tell me she got a day job.

I could write an essay on the topic of “rights”, but it would be easier to simply link to someone else who has already done the hard work.

http://atheistethicist.blogspot.com/2008/04/whats-important-about-rights.html

Jake:

True. Which is why I didn’t make it. And, frankly, after re-reading my post, I cannot see how you thought I did.

Sailorman had it right when he said

So, Jake, when you say

you are right. But this discussion has come about in the context of the example that Amp gave; that we are in a great debate on the right of same-sex couples to have a particular kind of bond between them framed as a civil right, a right that our Constitution says our government is bound to protect. On that basis, where people think rights come from is significant.

If they think our rights come solely from a societal consensus and are to be created and expressed in our laws then making the kind of change you want is essentially a procedural issue. It’s also close to saying that the government’s role is to create rights.

OTOH, if you think that rights come from our Creator (in whatever form you think that Creator takes) and that government’s role is to protect rights but not to create them, then you have to convince people that their interpretation of what God has given us as rights is incorrect. You have to understand that telling people that their rights are not God-given in the first place is in direct contradiction to what they were all taught in school and in church. As Robert states, a whole lot of Americans believe this. I certainly do. The arguments above are a good exploration of the consequences and effects of the idea that there is are no such things as natural rights, but you’re preaching to the choir (!) if you think that this is going to help you convince people of the un-Constitutionality of the present legal environment.

So my statement was not intended to prove the existence of natural rights, or natural law. It was intended to explore the consequences of what a belief that no such thing exists has for it’s proponents in America.

Manju:

The First Amendment applies to the Internet (at least, I hope it continues to do so) because it is perceived that there is a logical equivalence between a printing press and a blog (to oversimplify a bit). The Loving precedent only extends to gays if you believe that a desire to engage in homosexual behavior is equivalent to race.

ron, i think the burden of proof goes the other way. the state must demonstrate a compelling governmental interest in order to deny a person liberty. the 14th was written in the context of race, but it isn’t restricted to it.

similary, we don’t’ have to demonstrate that left handedness is similar to race in order to determine that the 14th prevents the govt from denying lefthanded people the right to vote.

Where does society get its rights? On what basis does society have the right to grant or to deprive an individual or a small group of individuals of life, freedom, property, happiness, or anything else? In your line of reasoning the only meaningful answer is power, a might makes right argument. We have rights because we have forced the main power center of society – regardless of social organization, we call it The State – to grant them. The means can vary: votes, bribes, guns, wars, revolutions, etc. But regardless of the means, the fundamental principle of rights you advance here is vulgar Machiavellianism. You’re not talking about “rights” — you’re talking about “privileges,” that which the paternal ruling powers will condescend to grant the people they oppress.

Yet it also rests on a simplistic view of “nature” – God or The Discovery Channel. As an atheist, I don’t ascribe to a divine sense of nature, nor a mystic notion of Nature, but the “nature show” sense of nature is pretty shallow, too. Nature shows rarely show groups of early humans collaborating, reasoning, making collective decisions – but they should. We used to be prey, but we banded together; and over a long process of evolution, interacting with our environment and changing with it, we developed brains capable of creativity, reflection, abstraction, projection, planning and experimentation. It didn’t happen over night, nor without fits and starts and lots of backtracking (because life is hard, and the powerful tend to be assholes), but we have used this intelligence to change society, to innovate its principles of organization and mechanics of member participation.

Democracy is one such innovation. It’s not monolithic, nor mystical, and we have a lot of different ways of putting it together. But the reason democracy is a preferable innovation compared to, say, feudalism, is that it relies upon dialog, conversation, debate, argument, appealing to one another’s reason and sense of “what is right” (morals, common decency, the “don’t be an asshole” rule); and even after a decision is made, often by majority rule (or as we so often see, by influence of powerful special interests — Halliburton, just to name one), the matter is never fully settled, it can be revisited and overridden. All of which requires things like freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, etc., because the democracy won’t function very well without them. Rights are derived in part from the systemic needs of democratic participation: individuals and minorities need protection from majority preferences to silence views they disagree with.

Yet rights are also derived from the dialog itself: “moral-suasion,” “enlightened self interest,” “giving a shit about someone other than yourself” — advances have been made in the areas of civil rights and human rights by virtue of appealing to not just “Reason” but to Empathy (not without a lot of struggle, of course.) You know, that thing Sotomayor got so much crap for. Are reason and empathy natural? Are they a part of human nature? I think so, and in this sense we might more coherently discuss natural rights. Whether we got reason and empathy from a divine creator or from a selfish gene or whatever origin you prefer, they are inherent parts of human nature. Rights that endure derive from these two basic aspects of our being.

I couldn’t disagree more. Where rights come from – God, Jefferson’s cat, Satan, Thor, Colonial society, modern society, the frozen foods section – doesn’t matter in determining who that right extends to. I think you’d have to agree to that where the right to freedom of speech is concerned. Freedom of speech (and of religion) is nowhere in the bible determined by the Christian god. Are you going to deny that freedom of speech is a right? You, and people like you, cherry pick from your religion to justify your position on particular rights. The lack of consistency shows beyond doubt that where rights come from, people or the supernatural, isn’t an important part of the debate.

i don’think the founders would agree with this formualtiion. their rationalist/deist outlook rejected the notion that something is rational or good because god says it is, in favor of the notion that god likes something because it is good or rational.

so the good can be known in this formulation. and its know thru reason and observation, not by miracles or revalations. there’s was a scientific outlook.

liberalism from its earliest beginnings was an open philosophy, profoundly aware of the limits of knowledge…and here’s where it probably diverges from the more doctrinaire libertarian constructions of rights. so if we hold the truth that all men are created equal to be self-evident, and that as a fundamental principle the govt should practice equal protection under the law and not deny the right to life liberty or property to any individual w/o a compelling interest or due process of law, it stands to reason, especially knowing now what we do about homosexuality, that the right to same sex marriage is protected in our liberal regime.

this is less of a creation of a right, than a natural extension of an already established fundamental right.

@Manju

The physicist says there was no “before the big bang”. Just like there was no “outside” the big bang. At the moment of the birth of the universe, there was no dimensionality, only a point in space and time.

The Big Bang is t=0, and there is no negative.

Likewise, if the universe were curved inwards, there would be no “after” the big crunch, or “outside” the big crunch – the universe is a closed cosmic egg. However, the universe is curved outwards, which means we go out by the slow death of galactic wasting away – the universe gets spread over an expanding infinite space until there is not enough entropically accessible energy at any point to sustain life, and spends all eternity being a vapourous pseudovoid with a few dead cinders in it.

At any rate, the only problem with cosmology is that the Dark Energy fudge factor means that our understanding of the universe is almost certainly wrong… but we have no idea what we’re getting wrong. But the big bang thing, yeah, everybody’s pretty sure that’s how it works.

Science.

But it does matter in determining what those rights are. If you think that rights come from a God that condemns homosexual behavior it’s pretty unlikely that you’ll accept the concept that homosexuality and heterosexuality are equivalent and that rights extended to the latter should logically extend to the other. You’ll say “Marriage is a bond between a man and a woman only – calling a homosexual couple’s bond marriage is absurd and a change in marriage’s definition and nature,” and “Homosexuals have as much right to marriage as heterosexuals do – they just don’t care to exercise it.”

This is where a lot of people come from in support for civil unions. They are willing to tolerate a de novo legislative construct to permit homosexuals to have some protection for their unions. But it’s a legislative grant – it’s not a right, like marriage is, because a homosexual bond simply cannot fit the definition of marriage as presented under the dominant religions in the U.S.

RonF,

First, thanks for admitting that there is no argument against marriage equality that isn’t based on religion. Then, let’s remember that we don’t generally consider “my religion says so” as a valid basis for forming public policy.

As for the larger argument you’re making, consider the implications. By that line of thinking, we should ban all non-monotheistic religions. You think our rights come from a God who condemns idolatry. We should also ban bacon. Our rights come from a God who told us not to eat that stuff.

It is one thing to say that our rights come from a divine source in the sense that every human being has value and worth as an individual, that that value comes from something outside of ourselves (a soul or whatever), and all our rights ultimately flow from protecting or respecting that value and worth. When you look at the rights considered “self-evident” in the Declaration of Independence – life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness – it is pretty hard to argue the Founders had more than that basic sense of value and worth in mind when they spoke of being endowed with rights by our Creator.

If you think that translates into policy prescriptions that conform to your understanding of Christianity, I think you need to think very carefully about what it means to go there.

Jake

I couldn’t agree more that our desires are part of the natural world, Jake (that was my point after all), and if Amp had said simply ‘They don’t. I want them to and think they will in my lifetime. But we’re not there yet,’ then his statement would have been completely unexceptionable from a scientific/rational/phenomenal point of view because such a statement does not invoke value, but merely describes a state of affairs. But that’s not what he said – which was:

Now, I don’t need to tell you, do I, that ‘I want such and such to happen’ has absolutely no moral force whatsoever? If it did, then all desires – all the way from wishing to indiscriminately murder passers-by on the street to wishing to establish universal peace, love and happiness – would be morally justified.

Do you believe that, or do you believe that desires themselves need to be subjected to some kind of adjudication, so that some can be said to be good and others evil?

RonF,

I hope you’re done editing your comment, because every time I read it, it gets worse. Under this terminology, marriage itself is a legislative construct, not a right. The right to marriage in Loving is that given that states have created legal constructs called marriages and given that we treat these constructs as fundamental to our lives, you cannot deny someone the right to marry based on race or ethnicity. Any state or all the states could wipe marriage from their statutes tomorrow, and it would violate nobody’s “right to marry.” Plenty of people on the left have suggested that the states only recognize civil unions for anyone – gay or straight – and leave marriage to the churches. Personally, I’d be fine with that, but I haven’t seen your side jumping on that bandwagon. Equality under the law is too much. You need to be privileged above other people (or, as the right likes to sneer “demand special rights”) or you’re not happy.

i thought that’s what you were getting at, ergo comment 37. while the founders did not speak of homosexuality their framework of thinking was not that we know homosexuality is evil because god says it is, but rather we know its nature thru reason.

theirs was an open philosophy, open especially to science, reason , and observation. after all, they insiturionalized the concept of separation of state and church knowing there is much we do not know. to read the reference to a creator as an acceptance of what is in scripture as the truth, is overreading it.

while they believed in god, they did not believe knowledge came from scripture, or at the very least it was trumped by observation and science. ie, the spirit of the enlightenment.

while their original intent may very well have been to exclude homosexuals— or for that matter blacks and women— from enjoying equal rights, the political philosophy they advocated is incompatible with this intent…which is the gist of MLK’s continual argument.

.

In The Postmodern Condition, Lyotard tackled this question because he saw that rejection of modernist rationalism led to place that seemed to have no grounding. His assertion was something he called “paralogy,” which I think could be offered as a 5th philosophical position.

Paralogy is about discourse — an ongoing conversation that can provide the basis for our collective understandings of what is “good” or “proper” and I think could be extended to what are our rights. Basically (and this is a major simplification), if we make sure that all voices are heard at the table, then the resulting discourse leads to the possibility of truth or goodness. The extent to which voices are silenced or some voices are heard at the expense of others is the extent to which we have no foundation. What he describes then becomes a process, not a premise. This rejects all premises in the sense that all things must be derived from some premise and suggests that humanity can create its own destiny.

This is not far from the “if I ask for it and can convince others to grant it, then it becomes a right” argument that was alluded to in some of the comments. For me personally, this felt quite scary at first because it is moving target and not solid a solid foundation upon which to stand. But the more I’ve contemplated in the past 15 years, the more I like it.

We are our own creators. Thus, the rights exist because we speak them and other people listen. We are the creator who endowed us our unalienable rights.

This, of course, is problematic in the practical world. In the practical world some voices are favored and often favored because of violence or threat of violence. But it is Lyotard’s point that we do not need moral grounding to understand that such displays of power are wrong because we need only understand that paralogy cannot be achieved under those conditions. Such violence and such refusal to hear others disrupts the conversation and taints the results of the discourse.

I will admit that I am not wholly satisfied with this but I like it better than the “natural” or “god-given” discourses. In the end, I believe we should hold ourselves accountable for how we treat others and Lyotard has provided a process by which we can come to that accountability without appealing to something beyond ourselves.

I’m one of these people. I still haven’t figured out why the government has any interest in marriage and it certainly isn’t a right in the legal sense because we are required to gain a license from the state to do it.

If we let go of the legal marriage and left it up to churches or whoever, then we would need to rethink a whole bunch of laws such as child welfare, inheritance, and taxation. But I think these laws need to be re-thunk anyway because as it stands right now, children are property, the state has it’s fingers in inheritance (which is double taxation in most cases) and the tax codes are extremely unfair to single-parent households, single people and so forth.

We should take a long look at how Scandinavian countries handle this question. For the most part, I think it is superior to the US system.

@Pattie – couldn’t a state government state that any and all existing and future laws, contracts, regulations, and by-laws respecting marriage shall immediately be applied to civil unions, and that all existing legal marriages shall be recognized as civil unions, and that from henceforth the state or municipal governments will wash their hands of “marriage”?

SiF – that’d be my approach. Make everyone equal before the state, and make “marriage” a religious concept between individuals and their church and God/s. Me and my wife have a civil union from the state which delivers to us our civil rights, and we also have a private religious santification, none of the state’s business. That would be fair to everyone.

@Robert – an interesting side effect of the “state out of marriage” is that it would actually allow gay folks to get married – married-married, not just civil unioned. I mean, if the state doesn’t have laws covering marriage anymore… then nobody can tell a United Church minister (or their buddy Joe) that he cannot, in fact, marry a couple of men. They signed the paperwork for the union, and they say they’re married.

Ultimately, it would make marriage just a word… which means polygamists could legally call their relationship a marriage. Yes, you would suddenly be able to “marry” your dog or your kid. You’d still be arrested for having sex with ’em, though.

But the only one of those that would actually have legal standings would be the ones backed by a civil union, which would exclude everything I listed in the second paragraph.

Interesting side note – most Latin American countries have this distinction between civil and religious marriage – though without any civil rights or recognition for gay relationships. It goes back to powerful anticlerical movements in the region after Church interference in state business became too much to tolerate. You have your civil marriage with a JP, and you’re legally married. Then, if you want to and the church will have you, you have your religious ceremony.

Lots of interesting stuff here — I’m sorry I haven’t been responding, I’ve just had too much work to do! But I am reading, fwiw….

Unless you claim that the right to free speech or the right to bear arms comes from some god or other I think that your argument is wrong.

I’m going to consider your comments to be desperate grasping at justification of your own prejudices unless you can point me to the religious texts that show that the following rights come from your god:

Free Speech

Freedom of Assembly

Freedom of Religion

Freedom from Unreasonable Search and Seizure

Right to Vote

Prohibition of Alcohol

Repeal of Prohibition of Alcohol

Due Process

Freedom from Cruel & Unusual Punishment

Freedom from Slavery

jake: the prohibition amendments aren’t considered part of the bill of rights.

That’s true, Manju, but I’m talking about Constitutional Rights and not just Bill of Rights rights. Amendments are part of the constitution whether or not such an amendment is part of the Bill of Rights, no?

(I’ll note that Women’s right to the vote is also not part of the Bill of Rights yet nobody can question that that is a constitutional right.)

And how weird is it that Manju and I are mostly in agreement? I’m not sure if that’s ever happened before. If you live long enough, you’ll see everything there is to see. I guess.

Is the “right” at issue in gay marriage, properly construed as “a right to marriage”? I thought it was “a right to equal access to institutions of the state, including the protections and advantages those institutions confer.”

yes, that the right way to say it though i think the constitution uses “privileges and immunities”. “right to gay marriage” is sloppy because it appears to read a new right into the doc which is not what we’re doing, even if we were to accept amp’s anti-natural rights postion.

rather we’re applying an existing right (to equal protection) consistently, imo.

Most of the ‘are no natural rights’ responses here have pretty much ignored the problem of ‘should’ in: “So I don’t think — for example — that same-sex couples have a right to equal treatment under the law when it comes to marriage, in most US states. They don’t. They should, and I think they will in my lifetime.”

I wrote

Myca also had helpful thoughts in that area.

Sailorman, you responded with:

But how does this get above “I want a piece of candy” or “I want to punch you in the face”?

What in the world does “objectively benefit its populace” mean in that kind of context?

How does “All I need to do is to believe that I’m right” help anything? Do you think that the Christian anti-homosexual marriage people don’t believe they are right? Do you want to appeal to something beyond which one of the two of you happens to hold more power?

If you want to say that descriptively, rights FUNCTION however the society lets them function, I guess you are right because it is effectively a tautology. But it is strange to hear people argue positions like

A) I don’t believe in rights

B) Homosexuals should be allowed to marry.

The ‘should’ is just a rights-based concept smuggled in the side.

Now the problem of what to do with people who have conflicting views about rights (i.e. lots of right-wing Christians and more pro-gay populations) is tough. Negotiating it is a problem. But it isn’t a problem that is avoided by denying the whole concept of rights–at least not without letting in a whole host of other problems.

Also, from a purely practical view, is anyone aware of major civil ‘rights’ progress (i.e. better treatment of minority groups) that has not been about applying more generally understood ‘rights’ and trying to make sure that they get applied to the minority?

It feels like you are trying to throw out the only functional tool.

Sebastian: I’d reconcile this by pointing out that at this point in history we’ve already determined what rights the people should have…ie, those that are inthe bill of rights. amp is conflicted by the fact that these rights are derived from the doctrine of natural rights, which i he doesn’t believe in. but my answer to him is it doesn’t matter, since we are not creating a new right.

the problem we’re facing now is less fundamental. its do we apply these existing rights to homosexuals. does the state have a compelling reason to deny equal protection to same sex couples? thus, the issue facing us //s the loving precedent.

i’d say you’d have a point if we were trying to legislate some of the rights we see in the UN charter, like say the right to basic food and shelter. to read that into the document would create a constitutional crises, but that’s not what we’re doing.

Can you explain this in more detail? I don’t understand what problem “should” creates when discussing whether or not natural rights exist.

It will be easier to ask you what “should” means in that context, Jake. If you don’t believe in rights, or some outside higher being/entity/power which has its own preference for how the universe should be, then where does “should” come from? What does it mean?

To clarify – I am aware of at least two different ways that people mean “should”.

“I should get some work done this afternoon.” This means that I have things on my plate, and my outcomes will be better, I think, if I get some of that work done today rather than (say) drinking beer and watching “Dancing With The Stars” on the DVR.

“People should not kill puppies for fun.” This is a moral judgment. Killing puppies for fun is intrinsically wrong. It violates some moral order, some natural right on the part of the puppy not to die for the whim of a higher creature. If you prefer a positive formulation, “people should be nice to puppies”.

In the former use, I am just talking about my preferences and plans. In the latter use, I am talking about right and wrong. Right and wrong relies on some framework to give it meaning; can be natural rights, can be God, can be any of a number of things, but it isn’t just “I don’t like puppy-killing” or “I just like puppies.”

Amp is saying that there SHOULD be equal treatment of people under the law. That seems an awful lot more like the 2nd kind of “should” than the 1st. Sure, there are pragmatic arguments for equal treatment that could be deployed akin to my gettng-some-work-done arguments – it’s easier to have one set of laws, it’s easier if there aren’t big gay protests all the time, Amp has gay friends who want to get married and it would save his ear a lot of chewing if they could so they’d shut up about it.

But if he means it in the “equal treatment under the law is the right thing” way, and I am pretty sure that he does, then people who DO believe in rights (and who structure our moral arguments that way) have a legitimate inquiry for Amp, which is “huh?” Whatcha basin’ it on? If God isn’t telling me “be nice to the gays and let them do what you do”, if natural law doesn’t inform us that “equal treatment really is the right way to go” – then why isn’t it just about power? Why isn’t it just about who has more votes, or guns, or money?

And if the latter, then where does “should”, in its 2nd sense, come into play?

And Manju, that the basic list of rights is kind-of settled (and not even all that well-settled, I must say) doesn’t obviate the problem. We can’t solve epistemological questions by saying “well, grandpa had the same problem, and he seems to have managed to find an answer, so I don’t need to worry about it.” We can kick the can down the road – it didn’t kill grandpa NOT to have an answer, so to hell with it, I’m not working on it – but we haven’t solved anything, we’re just accepting the existence of ambiguity.

Why not? Granted, it’s a moral judgment, but so what? Moral judgments can certainly be generated by things I like or don’t like. Moral judgments are entirely subjective, they become part of a moral or ethical code (or a right) when enough people hold the same value.

I don’t like killing animals. I think that it’s morally wrong to kill animals. It’s a moral judgment. However, since not enough people agree with my moral judgment in this area that is not part of our collective moral code. I believe that we should let animals live out their natural life spans. That comes from me, not from the supernatural. You believe that we should be able to kill animals for sustenance. That comes from you, not from the supernatural. Which one of those is a natural right? Are both of them? Are neither of them?

That’s why I don’t understand why “should” creates any sort of problem when talking about the existence or non-existence of natural rights. There’s some basic level of communication & comprehension failure going on for me on this subject.

Because in addition to establishing rights, the government also has goals and obligations: protecting its citizens, fulfilling its constitutional mandates, etc.

If you accept that the governmental framework exists, and if you accept that that framework establishes certain things as “bad” (dissolving government against the wishes of its citizens) or “good” (increasing the general wealth and happiness of its citizens) then you can easily make objective good/bad claims within that context. You only need to assume certain things about the government; you don’t need to get to natural rights at all.

Personally, no: I don’t believe that there are any “natural,” “human,” or “unalienable” rights.” What else could I appeal to? Note that this is a very different phrasing from whether or not I believe that humanity would be better off if those rights existed.

I am quite aware of the fact that, were I in a sufficiently small minority, I would lose many of the rights that I value.

It’s not a tautology, it simply defines “right” the same way that we define “law.” In my view that is a correct definition.

You may be familiar with the phrase “a right with no remedy is no right at all.” If you concur with that statement, the similarity of rights and laws becomes obvious.

But (here we go again) do you think that those “generally understood rights” exist at all outside the legal (constitutional) context?

“Can you explain this in more detail? I don’t understand what problem “should” creates when discussing whether or not natural rights exist.”

It is a problem because the whole concept of ‘should’ implies that there is a right thing you ‘should’ do and a wrong thing that you ‘should not’ do. The discussion of rights is one of the most important frameworks we use to discuss how we should and should not treat each other–especially in a government/citizen interaction or citizen/citzen interaction. So a question of what a government ‘should’ do in treating heterosexual citizens one way and homosexual citizens the same way or another way IS a question of natural rights. Because if it is just a question of government given privileges, there isn’t a ‘should’. There is just an ‘is’.

It feels like we are having a baby and bathwater moment here. You don’t think that natural rights come from “God”, but many of the framers didn’t either. The point they were trying to frame is that rights are intrinsic to being people, not just something that governments may allow to people when they feel like it. It isn’t super-crucial where these rights derive from, the most important point is that they belong to people by virtue of just being people. They are not a special dispensation from the king or the government.

And rights aren’t necessarily the be all and end all of the discussion either. Any time there are multiple rights, they are going to need to be mitigated against each other. That wasn’t a mystery to anyone in the discussion over the last 300 years either.

There can be all sorts of disagreement about where natural rights come from. But throwing out the whole thing just because you don’t like one theory of where they come from seems crazy.

I don’t concur with that statement the way you are using it. Ubi jus ibi remedium is an argument for creating a remedy, not an argument for denying the existance of rights. You are effectively inverting the meaning of the phrase.

And that is how civil rights advances have tended to happen in the real world. First you get people to recognize the right THEN you create remedies to protect it.

Absolutely I think so. The legal context isn’t everything. The legal context is at best a pale reflection of the moral understanding. If it isn’t, all you get is whoever has the most power ramming stuff down everyone’s throat. Which we have plenty of, I understand. But recognition of the moral importance of individual rights of citizens has been one of the few things that has fought that over the past 500 years or so.

I don’t see how it is a question of natural rights. Natural Rights posits that rights come from somewhere other than people. Treating one sub-group differently than another has nothing to do with natural rights and everything to do with human interaction. If it is just a question of governmentally given priveleges, there is just as certainly a “should” (or, more correctly, many different “shoulds”) as there is an “is.”

Yeah, and I disagree with that. There are no rights intrinsic to being a person, IMO. I can’t think of a single one. Every right that I’m aware of, existing or merely wished for, is not intrinsic to being a person. If we want to just look at the rights in the Bill of Rights, which of those are intrinsic to being a person?

There can be much more than that. I’ve yet to see evidence that natural rights exist. I’ve yet to see a right that can be unquestionably called natural.

It seems from this statement that you think that there are rights which are “intrinsic to being people,” and you’re only arguing about what those rights are and how we define them. Is that a correct summary?

you’ll find me talking about the legal issues because I don’t agree that there are rights which are intrinsic to being human (a.k.a. natural, human, unalienable, god-given, etc rights)

Actually, the most important point of this thread is that it’s not clear if any rights do belong to people merely as a virtue of their humanity. That’s pretty much what the rejection of natural rights implies.

Unless, that is, you want to come up with some way of defining “natural rights” as significantly different from “rights people have because they’re people.” but I don’t think you can do that.

I certainly agree that is what rejection of natural rights implies. Which is why it is odd for Amp to do so and then immediately afterward suggest that homosexuals should be allowed to/have the right to marry.

You have yet to explain why this is odd. “Should” in no way suggests the existence of or the belief in natural rights. “Should” suggests that Amp’s moral code contains the right of marriage regardless of sexual orientation. Amp’s moral code is in no way related to the concept of natural rights.

I’d really like it if you could explain your definition of natural rights and name some rights that you believe are natural rights. As it stands it seems to me like you are saying that “should” can only relate to natural rights and not to anything else. If that’s what you’re saying, you need to provide some kind of evidence that supports your position.

Why not? Granted, it’s a moral judgment, but so what? Moral judgments can certainly be generated by things I like or don’t like. Moral judgments are entirely subjective, they become part of a moral or ethical code (or a right) when enough people hold the same value.

Well, that’s the fundamental disagreement, then. I disagree with pretty much all of this. Slavery, to name one example, does not become moral or ethical even if 100% of the population, slaves included, think it is. And even if every other human being tells me I have the right to own other human beings, and the laws support me and uphold me, and fiery angels appear in bushes to reassure that it’s right – it isn’t.

“Should” suggests that Amp’s moral code contains the right of marriage regardless of sexual orientation. Amp’s moral code is in no way related to the concept of natural rights.”

No, ‘should’ suggests that Amp thinks Amp’s moral code ought to be applied to the society as a whole.

Robert,

Are you saying that within the societies in which it existed that slavery was not moral?

Everybody thinks that their moral code should be applied to the society as a whole. Your response is irrelevant to the question at hand.

You still need to explain how that is related in any way to the existence of natural rights. You also need to provide an example of a natural right.

Wow, comment #72 became botched and uneditable in a hurry.

“Everybody thinks that their moral code should be applied to the society as a whole. ”

That isn’t true. There are entire religious sects that believe the exact opposite. See any gnostic religion for example. See also vast swaths of Bhuddism.

The problem in this discussion is that you just want to avoid the phrase ‘human right’ but invoke all of the concepts.

“You still need to explain how that is related in any way to the existence of natural rights. You also need to provide an example of a natural right.”

No, you need to provide a persuasive argument for the extension of minority benefits without appealing to ‘rights’. You need to provide a method of talking about laws avoiding minority oppression that doesn’t talk about rights. Talking about rights is a very normal and understandable way of talking about such things. The rights-free method of talking about such things is at best cryptic, and in fact hasn’t been done here at least.

It is logically possible to believe the “nietzsche: there is ultimately no basis, rational or otherwise, for any of this but if you want rights you simply must assert them as a will to power” version. But very few people on a feminist blog are going to be willing to argue that way. Hell, very few non-authoritarians anywhere are going to be ok with arguing that way.

If you want to argue that “homosexuals should be allowed to marry” has the same moral force as “I like candy” that isn’t very powerful.

If you are appealing to some sort of moral imperative, you are just smuggling in rights and mislabeling it in the discussion.

Discussions about how morality plays out in the interplay between governments and citizens are discussions about rights.

There are basically two things you can think about rights: that they are wholly created and at the whim of government, or that they are held by people and governments can be judged by how they respect rights or fail to respect them.

I’m not aware of any minority progress anywhere under the first view. Civil rights tend to get vindicated only sometimes, and only under the power of the second type of argument.

This is your mistake, right here.

My belief that homosexuals should be allowed to marry stems from the same process as does my belief that chocolate is good. But the process does not control the result. The arguments are not equivalent.

Compare

a) belief that the value of thr gravitatino concept is quite accurately understood

and

b) belief that the effects of human interventions on long term climate change are almost completely understood.

See? Same process, different inputs, different arguments.

Your whole rebuttal seems to focus on the underlying beliefe that there are only two levels of “truth”: God/natural truth, and everything else. I.E., you are implying that unless you claim authority from god/nature/whatever, your arguments have no relative effect.

Bollocks. As I have said a few times–as as you have apparently ignored–there are multiple different ways to believe that something should be a right.

You can claim superauthority from god, nature, etc.

You can just have your own random belief, like “I like candy.”

You can have a belief which you believe is correct through logical deduction from some other postulate, such as certain assumptions about the role of government.

Or you can have other bases.

Why you continue to phrase this as “natural rights or candy” is beyond me.

Are you saying that within the societies in which it existed that slavery was not moral?

Yes. Further, I am saying that this is obvious.

Sebastian,

Whether or not I need to, “to provide a persuasive argument for the extension of minority benefits without appealing to ‘rights’,” whatever that means, you absolutely do need to define your argument by clearly explaining how “should” is in any way related to “natural rights” and to provide an example of a “natural right.”

I can easily provide a persuasive argument for the extension of benefits to minorities without appealing to some nebulous definition of “rights.” I’m convinced, however, that you will just expand your unstated definition of “natural rights” to include whatever example I give. As a result, I would like you to clearly explain your definition of “right” and of “natural right” and to give an example of each. Until you do that, it’s like trying to discuss what a fnord looks like – impossible.

It isn’t obvious. If slavery was sanctioned and even lauded within a society how is it obvious that slavery was not moral within that society?

If slavery was sanctioned and even lauded within a society how is it obvious that slavery was not moral within that society?

Because slavery breaks natural law. People have a right to control/”own” themselves. This right is inherent and intrinsic, and a society which undermines rather than promotes this right is an immoral society.

If rape were sanctioned and lauded within our society, wouldn’t it be obvious to you that rape is nonetheless wrong?

I don’t have time to go back through the thread and attribute every argument that I’m going to reference to the person who made it, and I realize that not quoting directly increases the chance I might mischaracterize someone’s argument. My apologies in advance …

It seems to me that many higher order mammals, including apes, show signs of valuing fairness and cooperation, and this forms a certain “natural” basis for the system of rights we have today and our notions of justice, etc. However, the natural basis of this seems to be very limited to the in-group or even to the individual. For example, a chimp given cucumbers after seeing all the other chimps get grapes will turn his nose up at the cucumber – he senses the situation is unfair – but I don’t know that the grape-eating chimps will sense any unfairness and want to share their grapes. And even if they do share their grapes within the group, they’re certainly not going to share with chimps outside their group.

It also seems to me that the expansion of rights over the centuries is tied to an expansion of what constitutes the in-group. Without reaching a point where most people believed in absolute equality between blacks and whites, enough people came to believe that blacks were sufficiently like whites that enslaving them and treating them like chattel was wrong. Without reaching a point where most people believed in the absolute equality between men and women, enough people came to believe that men and women were similar enough in their capacity for rational thought that denying women the vote was wrong. Similarly, the debate about gay marriage is at its core about whether gays are similar enough to straights that their relationships belong in the same legal category.

I don’t know if this progression is “natural,” and I’m not sure how you would even answer such a question. I am kind of disturbed to see arguments that slavery wasn’t wrong until we decided as a society that it was wrong. Accepting that means believing that blacks were objectively inferior to whites until whites decided they weren’t, and I don’t see how you can make that argument. Black people have always been just as human as any other human beings, and the inability of white people to grasp that doesn’t make it less true. There’s a limit to the subjectivity that can be brought to this topic without entering into absurdity.

So in one sense, Amp is absolutely right. Man has only those rights which he can defend. But to argue for the expansion of rights, I think we do need more than “because I want to.” I think those questioning where the moral force for progress comes from under the “I want it” system cannot be just waved away. If the only weight behind the expansion of rights is personal desire, than personal desire on the part of people who don’t want to expand rights carries just as much moral weight. “I don’t want to free my slaves because they provide lots of free labor that enriches me” becomes equal to “Human beings are not chattel to be bought and sold.” Or take Myca’s question of how we can talk about human rights violations in other countries where those rights don’t legally exist. On what basis do we say that the people in, say, Darfur shouldn’t be killed indiscriminately, that women shouldn’t be gang-raped when they leave the refugee camps, etc.? The women there have no right to not be gang-raped because they have no means to stop it? Where are we going with this?

Let’s try the various formulations. I don’t want women to be gang-raped. The women themselves don’t want to be gang-raped. Women should not be gang-raped. How does the desire of one person not to be imposed upon stack up against the desire of another person to impose upon them? If rights are only a matter of who has the numbers and the legal system behind them, then the desire of a powerless person not be imposed upon does not have any moral force whatsoever.

To be clear, I don’t think the “rights come from God” people have a slam dunk on this. They do have a nice, one-word answer, but if you don’t believe in God, that nice, one-word answer is just a pleasant fiction, so I don’t think that advances the discussion much. I also don’t know that it makes a huge difference practically speaking because people who believe rights come from God can come to radically different conclusions about what those rights are and how society should be structured, just as people who think rights are a human invention can.

And I’m not entirely sure if my issue is with the definition of rights or the nature of “should” or “ought to” in these formulations, but I think that question is more complicated and more necessary than some people are acknowledging.

“I can easily provide a persuasive argument for the extension of benefits to minorities without appealing to some nebulous definition of “rights.” ”

Please do.

People keep saying that they can, but they don’t. At least not without appealing to some nebulous other term that isn’t any better than ‘rights’ and seems to be ‘rights’ without using the word.

I’m not saying that talking about rights is easy. Nor that the definition of what counts is clear in all cases.

But I am saying that throwing it all out leaves you with A) no easy way to talk about why minorities ‘should’ be treated under anything other than the will to power of the majority/power holders and B) no obvious major successes in improving the treatment of minorities outside of the ‘rights’ framework.

So you don’t have theoretical advantages, and you have obvious practical deficits.

Now it is possible that there are no such things as ‘rights’ and that all we have is will to power. But then all you are left with is the need to gain power over people if you can, and submit if you can’t. Everything else is just self-deception in that world.

If you honestly believe that is the world, I guess that is fine for you. But then don’t bother using words like ‘should’ because that just plays into the deception.

Sebastian,

I’m asking you directly for at least the 3rd time to please explain your definition of “right” and “natural right” and to give an example. Can you please do that?

Without evidence that natural law exists, this is rather meaningless. If you hold that faith, sure, it’s obvious. If you aren’t of that faith, there is no evidence and so it’s nonsensical. So you can say it’s obvious to people who have faith in the existence of natural law but you can’t say that it’s obvious. Can you provide any evidence that the right to control/own yourself is inherent and intrinsic? It seems to me that there isn’t any evidence of that.

Sure, rape breaks my moral code and I think it’s wrong. I would also think that a society that condones rape is an immoral society. I don’t dispute that for a moment. However, my moral code isn’t necessarily that of another society or even my own society. Within that hypothetical society rape would be moral, and that is undeniable. Since the moral values of a society are determined by that society it is unavoidable that, within that society, rape would be moral.

I believe that it is immoral to kill any animal except in self defense. Our society, however, believes otherwise. So killing animals is immoral and wrong to me but it is moral to you and countless others. As a result I must concede that killing animals for food is morally okay in our society.

Jake,

I’m not even sure how you’re using the word “moral.” You seem to be using it as the equivalent of what socially dominant groups want to do. Is someone more or less human based on how other people view them? Where women actually the intellectual and moral inferiors of men when men believed them to be so? That seems to the logical extension of your argument.

I don’t understand why we need this.

Why can’t we (for example) suggest that certain premises are correct, and try to adopt rights based on those premises? Or why can’t we come to agreement that certain processes are ideal, and try to adopt rights which align with those processes?

Well, yes. Of course. Why should your personal desire matter any more than mine? Why should mine matter any more than someone else’s?

To me, part of this discussion seems to be about facing the harsh reality that your personal preferences and beliefs don’t have any supernatural or extra-human morality. They don’t have any extra oomph just because you think you’re on the “right” side (pun intended.) If they do, then how are you going to explain all the opponents who think the same thing about their opposing viewpoints?

All that your framing does is to move the issue away from personal preference, to who can do a better job presenting their side as more favored by God, or more ‘natural,’ or whatever the trump card seems to be for that particular discussion. You’re still having the same argument; you’re just having it through proxy.

From my perspective, it is a much more honest and productive discussion if both sides stop fighting through proxy and actually try to come to some consensus on rights.

Morality is how one classifies right and wrong. I believe that killing animals is wrong, therefore I consider killing animals to be immoral. The society in which I live considers killing animals for food to be right, therefore the society in which I live considers killing animals for food to be moral. I must concede that while I believe that killing animals is wrong and, therefore, immoral that the society in which I live considers killing animals for food to be okay and, therefore, moral.

Does that explain it?

The dominant group, in terms of societal norms, certainly determines what the morals of its society are. Is there any way around that?

No, but it is moral within a society that believes women are less than men to consider and treat women as less than men. That doesn’t mean that it’s moral to every member of that society nor does it mean that it’s moral to other societies.

The definition of moral as I understand it is what Merriam-Webster has:

of or relating to principles of right and wrong in behavior

Am I totally off base?

Dude, are you even reading my posts?

Watch:

1) Postulate certain things about government: it should exist, and the role of government is to maximize the overall benefit to its citizens.

(Is that a nebulous definition of ‘rights?’ If so, please explain how. it might help me understand what the freak you are talking about.)

2) Make a claim that equal treatment of certain citizens is objectively and logically required in order to achieve the accepted role of government. In particular, make a claim that the overall benefit to all citizens of an equal society is greater than the overall benefit to all citizens of an unequal society.

See? not so hard. Assuming you read it.

I’m totally with Sailorman on this and I can only hope that his comments are clearer than mine have been. Comment #86 re-summarizes, yet again, the same points that I have been trying, less successfully, to argue.

Am I totally off base?

Yes. You are substituting the winners of American Idol (what society likes) as a substitute for moral reasoning.

Morality is not subject to majority rule. If you are contemplating morality and reaching conclusions based on what most people think, then you’re doing it wrong. “What most people think” is socially important, and has a huge effect on how people’s rights are respected or derogated in society, but it isn’t *morality*.

Without evidence that natural law exists, this is rather meaningless. If you hold that faith, sure, it’s obvious. If you aren’t of that faith, there is no evidence and so it’s nonsensical.

The fallacy of the legal mind; without evidence, it isn’t true. No, without evidence, you can’t know that it’s true on the basis of evidence. Evidence is not the only basis for knowledge. If I sneak up behind you one dark night and smack you with a baseball bat, you may have no evidence that I did it and no way to prove it, but the event nonetheless occurred. That isn’t nonsensical, it’s just an artifact of our inability to directly perceive truth and our reliance on (fallible) sense data.

So you can say it’s obvious to people who have faith in the existence of natural law but you can’t say that it’s obvious.

If “slavery is wrong” isn’t obvious to you, I don’t know what to say.

Can you provide any evidence that the right to control/own yourself is inherent and intrinsic? It seems to me that there isn’t any evidence of that.

No, I can’t. I’m not presenting you with a conclusion, derived from previous evidence; I’m presenting you with an axiom, a starting point from which we work.

You don’t have faith in the axiom. No worries, but also no skin off my nose.

Sailorman,

Explain to me why your line of reasoning does not allow the Holocaust to be moral. (Yes. I am Godwining this thread. I’m doing it because I am wondering if there is any limit at all to the relativism.) The Nazis had a personal desire to rid themselves of people they saw as parasitic stains on humanity. Who am I say that other people’s desire to not be killed in gas chambers has any more weight than the Nazis desire to be rid of those people? If the desire to live has no more worth than any other desire, there was nothing wrong with what the Nazis did.