I was cleaning out some files in my office at school the other day, when I found a copy of the introduction I gave in the spring of 2001 for two women who were doing an independent study with me in creative writing. The introduction was for their participation in the annual symposium at my school where students doing independent studies were required to present their work in order to get credit for the class. I’d met Cheryl and Edith (not their real names) the previous semester when they took Advanced Essay Writing with me, which I taught as a class in writing the personal essay. Each wrote a piece early on about the sexual abuse she’d survived as a child, and each had approached me separately about the fact that she wanted to be a writer and that the issue of sexual abuse was at the core of what she wanted to write about.

Responding to their work in the context of their ambition confronted me with a serious dilemma. I had already been writing about my own experience of abuse for some time, but I’d also always made sure to keep those details of my life separate from my work in the classroom. It wasn’t so much a distinction between personal and private that I wanted; after all, I was performing at readings and trying to publish poems that dealt with my abuse. It was more that I feared allowing too much of my own vulnerability into the classroom would undermine my authority as a teacher.

Edith’s and Cheryl’s were not the first student essays I’d read about sexual abuse. Indeed, by that point in my teaching career, I’d read more than a few essays in which students talked about their encounters with blackmail, domestic violence, alcoholism, and even female genital mutilation. Edith and Cheryl, however, were the first who told me they wanted to be writers writing about their issues, that they wanted to claim a public voice in which to speak not just for its cathartic or therapeutic value, but also about why what their abusers had done to them should matter to their communities–Edith was Latina; Cheryl, Haitian-American–to women as a group, and to society at large. Even more than writing instruction, talking to each of them quickly made clear, what they wanted was a mentor/role model.

My first response was quintessentially teacher-like. I recommended books they could read and I talked to each of them about the value of counseling in coming to terms with their experience, but they wanted more. Edith was especially articulate about this. What she wanted, she said, was someone she could talk to, someone of whom she could ask questions face-to-face, someone who had been through what she was going through, not just the abuse itself, but the desire to go public, with all its intimidating implications, and come out whole on the other side–precisely what she was afraid she would not be able to do. I asked to take another look at her essay after that conversation and, as I read it a second and third time, I ticked off in my mind each moment where I could tell she was holding back, where she was purposely not saying what she was afraid would split her world so wide open she might never be able to make it whole again, and I decided to come out to her as a fellow survivor, as just the kind of writer she’d been telling me that she was looking for. I wrote a long response to her essay and, when I got the second draft of Cheryl’s piece, which showed exactly the same kinds of weaknesses, I did the same for her, opening up a whole new level of conversation with each of them about what it meant to be a writer and what they wanted their writing to accomplish.

For most of the semester, those conversations were separate, but then Edith approached me about the possibility of doing an independent study in essay writing, since there were no more classes she could take. I suggested that she might want to talk to Cheryl as well, saying only that Cheryl also wanted to be a writer and that I thought they might have a lot to say to each other. Edith did; Cheryl agreed; they did the required paperwork and our independent study began in January of 2001. It was a remarkable experience, but I want to write about here is what happened towards the end of that semester when I reminded them that they would have to read at the symposium some portion of the work they’d produced. Frankly, they were terrified. The symposium would be attended not just by independent-study faculty, other student presenters and their guests, but also by the college president, academic vice president, vice president of student affairs, and other administrators. How, they wanted to know, could they possibly read any of the intimate, sexually explicit, sometimes violent pieces they’d written in front of that audience? What place did their stories have, what right did they have to place their stories, side by side with the scholarly and academic work that would be presented by the other independent-study students?

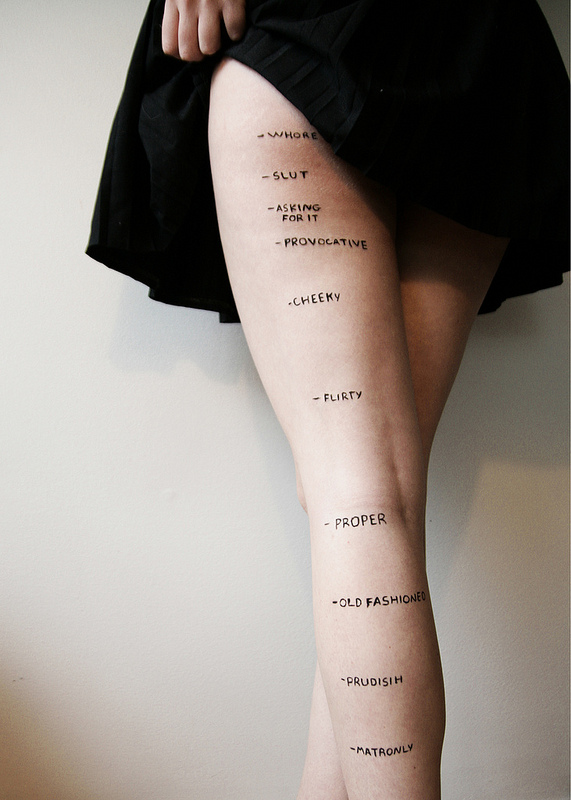

There was no easy way to answer those questions, nothing I could say that would make them feel safe, because they were right. Their stories were, at least from a traditional point of view, the antithesis of the scholarship that other students would be presenting. Not only were my students’ essays not research essays, but Cheryl’s was about the first time she was able to have an orgasm from penetrative sex, which her abuse had made it very difficult to do, and Edith’s was an angry and explicit condemnation of the male dominant heterosexuality that gave men permission to treat her like an object and of the men in her life who had done so, starting with the man who’d sexually abused her while her mother managed not to know about it. Each woman, in other words, had good reason to be afraid, and the more we talked about that fear, the more it became clear to me that I had to do something to share its burden with them, that this was the moment to be the role model they had asked me to be. So I told them that when I introduced them, I would do so by talking a little bit about myself as a survivor of sexual abuse and what being able to work with them had meant to me. This way, anyone at the symposium who had a problem with the content of their essays would have to come through me first. Here is the text that I read:

Twenty years ago, when I was beginning to come to terms with the sexual abuse I survived as a teenager, there were no male voices out there that I could use as models in making sense of what had happened to me; and there was as well much misunderstanding about what it meant to be a man who was once a boy whose body had been sexually violated. I remember going to the Syracuse University library when I was in graduate school, for example, to see what had been written about my experience and learning for my troubles from a study I remember little else about that most people believed boys who’d been sexually abused by men were most likely to become homosexuals, as if we had invited and enjoyed the abuse. I felt alone and afraid, and I think one of the reasons I became a writer is that the act of my putting my words on the page, their physical presence in the world outside myself, provided at least some reassurance that my experience was real, that it was important and that it deserved an audience, even if only an audience of one, myself.

The women who are going to read for you tonight, Cheryl and Edith, were also sexually abused as children. They are fortunate enough to have come of age at a time when the silence and fear that once surrounded this subject no longer dominates our public consciousness. Nonetheless, writing has been for them a way both of breaking the isolation that abusers inevitably impose on their victims and of making meaning, personal and political, out of their experience. I am honored, humbled and simply happy that they trusted me enough to help them learn the craft necessary to speak that meaning as compellingly as you will hear them speak tonight.

What they read may make you uncomfortable. It should. Abuse is ugly, and confronting it is never easy. If you look closely, however, and are willing to listen, there is beauty to be found in that confrontation–not the easy and often reactionary responses you hear from politicians and the media, but the carefully polished and hard-won moments of hope that let you know healing and transformation, both personal and collective, are possible.

When I finished reading it, you could hear a pin drop, and the uncomfortable silence continued until Edith, who read first, looked up from the last page of her piece, and received a well-deserved standing ovation. When Cheryl finished reading her essay, the audience stood for her as well, and not a few people–students, faculty, administration–came over to congratulate them afterwards. The only one of my colleagues who said anything to me was a guy from the Math department who complained that I’d made a mockery of the event by allowing my students to read such inappropriate pieces of work. We argued for a bit, neither persuading the other, and when he left, I was happy to recede into the background. Neither my decisions as the supervisor of the independent study nor the revelations I’d made in my introduction were the point of the evening, which was supposed to be Cheryl and Edith’s moment to shine, and I was happy and humbled and proud that they were indeed shining.

For myself, however, delivering that introduction was transformative. It was the first time that I’d publicly claimed my identity as a survivor of sexual abuse not just for its own sake, but as a legitimate perspective through which to understand and make decisions about actions I wanted to take that were not directly connected to my own sexuality. It was, in other words, the moment I first began to work through what a “politics of survivorship,” or at least my politics of survivorship, might look like. And I have Edith and Cheryl to thank for teaching me that.

Cross-posted on my blog.

It is inevitable that people will detransition – no medical treatment has a 100% satisfaction rate. But 94% of trans…