Via Andrew Sullivan, I read this article by Anne Lowrey trying to make the deficit understandable by putting it in terms of a household budget.

For our purposes, let’s use $60,000 as the government’s income and $85,000 as its expenses.

AdvertisementWhere does all of that spending go? Mostly, to mandatory programs, spending that does not change much year-to-year and is not easily reduced. But given that mandatory spending makes up about 60 percent of spending, if the debt is going to come down, these are the line items that need to change. Next year, Obama is requesting $17,400 for Social Security, $10,700 for Medicare, $6,100 for Medicaid, and $13,600 for other mandatory programs such as food stamps.[…]

The country needs to fund the Afghanistan war and the Department of Defense. This is not cheap: In fiscal year 2012, Obama is asking for $20,000 for overall security costs.

So far, my friend, you’re at $68,000. No cuts yet, and you’ve already blown your budget by about $8,000.

Obama’s budget primarily proposes cutting stuff from outside that $68,000. Obviously, that won’t do much:

So where to cut? The White House is mostly focusing on those nonsecurity, discretionary programs. Next year alone, the federal government plans to cut from 200 of them—axing some of them entirely. This saves a grand total of $750…

If people are serious about cutting the debt, then they have to be willing to consider cutting entitlements; they have to be willing to consider cutting military spending; and they have to be willing to consider increasing the household’s income, which is to say, raising taxes.

But there’s another, even more important requirement, and that’s addressing rising medical spending.

Lowrey says one thing that’s absolutely wrong:

Mostly, to mandatory programs, spending that does not change much year-to-year and is not easily reduced.

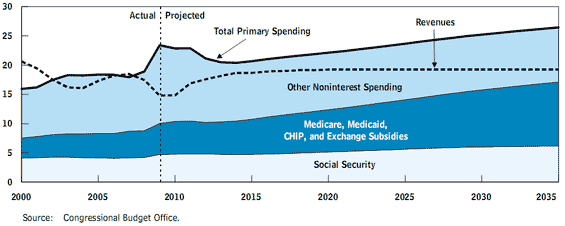

That’s simply not true. A big chunk of our spending is on Medicare and other programs that subsidize medical care, and that spending is changing year-to-year. It’s going up — going up so fast, that in the long term it matters more for our budget outlook than anything else does. Here’s a graph from the CBO:

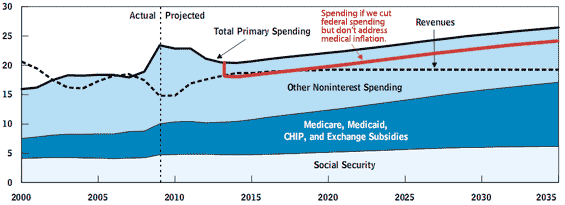

Okay, let’s say that we manage to cut our 2013 budget so severely that we wipe the deficit out (that is, our spending isn’t bigger than our income) — how does that change the budget outlook? Here’s the same graph. Except I’ve added a new line, indicating what happens if we get rid of next year’s deficit.

So in return for permanent spending cuts that will be politically difficult and cause real pain for many Americans (less heating oil in winter, less money to pay for college, etc), we’ll “fix” the deficit for five years. 2013 through 2017. Then, in 2018, we’ll be back to deficit spending. Does that seem like a worthwhile trade to you? If so, I’m guessing that you’re not someone who depends on Federal programs to stay warm in the winter, or whose ability to go to college (and long-term financial security) depends on Federal aid.

Let’s return to Lowrey’s household budget. We now spending about $17,000 of our household’s $60,000 income on medical expenses. But although the other items on our budget don’t change much year-to-year, our medical spending has been rising about $850 a year. That means that in a decade, if nothing changes, we’ll be spending $26,000 of our $60,000 income on medical expenses, and in 20 years more than half our income will be needed to pay for our medical expenses.

If we’re not addressing the rising costs of medical care, then we’re not addressing the real long-term federal debt. It really is that simple.

* * *

UPDATE: For further reference, here’s a graph showing how total health expenditures as a share of GDP have changed in the US and other countries. Big thanks to Charles for making the graph. Further discussion in the comments.

Data from exhibit 5 of “Health Care Spending In The United States and OECD Countries,” by Kaiser Family Foundation.

OK. So let’s freeze medicaid and medicare at their FY2010 levels and reduce the benefit per-capita going forward. It will be less care, and a bit less each year, but people will be able to plan for their reduced benefits and the onus for cost reduction will shift to individuals and the health care industry.

Or we can keep pharmaceutical companies from price-gouging the crap out of individuals, insurance companies, AND the government, reducing the strain on the budget, reducing the justification for insurance company dickery, and reducing the expense for the individual all with one mighty blow.

Which makes more sense to me than just punishing the individual for the actions of the pharma companies.

It should be no surprise that medical costs are projected to increase. The number of Medicare beneficiaries is rising. Some degree of inflation is occurring. If you want to address the issue in any depth, you have to look at costs per person covered in order to understand time trends and specific ways to trim costs.

(aside from a bigger public option, which is a big obvious helper but not the whole solution, and capping insurance company profits….)

Preventative care is really underemphasized. My doctor believes being fat is unhealthy (whatever, doctor. F U), but she just says “oh eat right and exercise” and vaguely waves her hands in the air. Likewise at the yearly exam I don’t get much of a lecture on my sexual health. There should be a lot more support and encouragement to try and stay well.

As you have quite correctly pointed out in the past, Ampersand, we would enjoy enormous health care savings if we were to convert to the vastly more efficient single payer health insurance model instead of the cruel, Byzantine and extraordinarily wasteful for-profit bureaucracies we have now in the U.S.

I would point out one meme that your post (inadvertently) promotes that we should kill and kill dead: that medical costs for our society shouldn’t be increasing. We’re an aging society with a huge demographic cohort about to enter into the primary ‘health care need’ years. Of course we should expect an increasing share of our society’s resources to be devoted to health care. Very few of us as individual 55 year olds would opt for purchasing a new computer or car instead of a needed mastectomy or hip replacement.

Moreover, while technology may provide some cost-saving efficiencies, the bulk of research and investment is going towards curing things we couldn’t cure before.* The decision as to whether we want to ‘cure 1,000 cases of disease X’ or ‘provide 100,000 people with high-speed cable’ (or whatever) is a thorny one, but I think a society based on exponential increases in knowledge is likely devote an increasing share of its productive capacities to curing diseases.

* At least, that portion of R&D which isn’t devoted to creating patentable and more profitable drugs that are not any more effective than their less-profitable patent-expired predecessors.

When I picture unemployed Americans “able to plan for their reduced benefits,” I imagine a plan more violent than the one they used in Egypt. Though I imagine Robert thinks we’ll suddenly have more jobs, without replacing the vanished paper wealth that caused the recession, because (Bayesian evidence against Keynes goes here). Maybe we should schedule our investment bubbles better?

More seriously, other countries seem to have increasing costs-per-person but with a slower rate and a lower starting point. (Our neighbor Canada and the Heritage Foundation’s “least paternalistic” country Switzerland both exceeded our 1995 costs in 2007 by per capita PPP. As you can see, others did not.) Does anyone have thoughts on how to copy what we know works?

I don’t often agree wholeheartedly with ballgame, but I do on this one.

I would point out one meme that your post (inadvertently) promotes that we should kill and kill dead: that medical costs for our society shouldn’t be increasing. We’re an aging society with a huge demographic cohort about to enter into the primary ‘health care need’ years. Of course we should expect an increasing share of our society’s resources to be devoted to health care.

I agree, agree, agree. I never have understood why growth of the medical field is considered a bad thing. We spend more money now on medical care than we did 20 years ago. So what? We spend more money on cell phones too and no one talks about the problem of cell phone spending. Indeed, the industry is considered wildly successful. Why should increased utilization, employment of more people, and longer lives for many people be considered a problem?

Yeah, this comment’s self serving. So what?

Robert wrote:

No, I have a better idea: Let’s switch to complete single-payer within a year! It’ll be much more efficient, and more people will get the health care they need with less stress.

Oh, wait: That idea won’t work because it’s not actually possible to get such an idea through our political system. It’s ideologically pure, and arguably works on paper, but it’ll never get off paper.

Which is the first, obvious problem with your proposal.

(Another huge problem is that you’re essentially calling for an enormous increase in health care rationing by wealth.)

Dianne,

I half agree. Medical costs should be rising relative to some baseline as we get more and better health care, but the US baseline is wildly out of kilter with our results. We spend way more money than anyone else for inferior results measured by pretty much every reasonable metric. So yes, I don’t see any problem with US spending on medical care as a fraction of GDP growing hugely over the next century, so long as that increased spending translates into improved outcomes for everyone. On the other hand, it is clear that the current system is hugely wasteful, so we ought to be able to take some substantial steps to decrease the cost of healthcare at the same time that we accept that overall healthcare costs are going to rise.

Of course, that chart is (government covered) health care costs as a percent of GDP so that rising trend isn’t just increased health care costs, but health care costs becoming an increasing proportion of the economy, but even that doesn’t seem like it is necessarily a problem. If, 50 years from now, I enjoy the same standard of living I have now (with the other half of the doubling of per capita GDP going into increased health care costs) , but I also can expect to live a few decades longer than I can now expect, I don’t think I’d have any complaints. If a hundred years from now, I enjoy the same standard of living instead of the 10X standard of living GDP growth would otherwise predict, with 90%+ of my income going to medical costs, but I also am still alive, I would definitely consider that worth it!

But since 90% of us haven’t seen any of the increase in per capita GDP over the past 3 decades, the more likely continuation of the current trend lines is that my income won’t have gone up in real dollars, but my medical costs will have gone up substantially, while the really good life extending medical care will be out of reach for plebs like me, and only available to the wealthiest 10%.

So, while I think that there are some major improvements that could be made in decreasing the baseline costs of our medical system, I agree with ballgame and Dianne that avoiding increasing medical costs is not necessarily a good goal. Instead, I think we need to resolve the deficit problem by taxing more heavily the one group of people who have been getting all the benefits of the increasing wealth of the nation (the rich). Since they are getting all our increased productivity, let them also pay for all our improving medical care!

I agree with everything Charles wrote in comment #9.

NancyP writes:

Ballgame writes:

But the US has a younger population than many wealthy countries; if an aging population was the main thing driving health care inflation, then we’d expect the US to have experienced relatively low health care inflation over the last few decades.

But the opposite is true:

(Big thanks to Charles for making the graph.)

The data is from exhibit 5 of “Health Care Spending In The United States and OECD Countries,” by Kaiser Family Foundation.

Looking at the chart, the US is an anomaly. There are countries who have had their health care costs increase as much as the US’s, but those are the countries that began with a low baseline in 1970. (Belgium, for instance, was at 4% in 1970 and shot up to 10% by 2003). There are countries that started with a baseline about as high as the US’s, but they’ve seen relatively low health care inflation. (Denmark started with a high baseline in 1970 — 8%, a point higher than the US’s 7% — but in 2003 was spending only 9%, while the US shot up to 15%. Denmark’s population trends older than the US’s — see Table 2 of this pdf file.)

The US is alone in starting with a very high baseline in 1970, and experiencing high inflation. From a cost-control perspective, it’s the worst of both worlds.

Dianne, first of all, what Charles said.

Second of all — barring some truly enormous increase in the amount of taxes Americans are willing to pay — the costs of medicare et al are going to increasingly crowd out other things that I think we should also be spending money on, like infrastructure investment and schools. If Federal spending on cell phones was having that kind of effect on the Federal budget, then I’d be as interested in cell phone inflation.

Finally, there is an actual limit to what we can spend. So medical costs won’t — can’t — continue growing faster than GDP forever. Instead, at some point, we’re going to drastically curb the rate at which medical costs increase. We might do this in a rational way that guarantees as many people as possible good health care. Or we can go with Robert’s system of letting the free market decide (i.e., if you’re sick and poor, you should just die). I’d prefer the former.

Health care costs going up is not inherently a problem. For them to go up the way they’ve been going up in the US is inherently a problem, however.

By the way, for anyone interested, I wanted to recommend “What Makes The US Health Care System So Expensive,” a series of blog posts by Aaron Carrol. That’s a link to the introduction; it’s really worth the time to read the entire series.

Really? I see an awful lot of talk about the problem of cellphone companies overcharging their customers.

Robert’s “let the sick and poor die first” plan also has the problem that being pennywise is often, especially in health care, pound foolish.

This story just came out in California yesterday. The report (pdf) suggests that cutting readmissions by just one day per patient would save 227 million dollars. But doing so would require longer initial stays in many cases, coordinated discharge planning, more patient follow-up, etc. All things that cost money, and when Medicaid reimbursements are cut, the incentive is to go the opposite way – push people out the door with less care because the hospital can’t afford to keep them any longer. (And if you force them to keep people longer by penalizing them for readmissions, rather than encouraging them to do so by increasing reimbursements, that just increases costs for cash-pay and private insurance clients, who are already screaming under the weight. 56% increase in premiums proposed by Blue Cross of California, don’t ya know.)

Jeez, Amp, I was agreeing with you.

*sigh*

The graph in your link goes to 2004. It is 2011 today.

What’s the difference? Well subtract 65 from 2004 and you get: 1939. Subtract 65 from 2011 and you get: 1946. Big difference … very big difference. The “% of Pop 65 Years or Older” just took a jump over the past two years.

Now, to be clear, I never claimed that “an aging population was the main thing driving health care inflation.” My exact claim was that we DO have an aging population, and — all things being equal — we should expect to be devoting an increasing share of our economy to be put to health care as we move forward. Those two claims aren’t quite the same thing.

I emphatically agree with you that our for-profit health care system is primarily to blame for our exorbitant health care expenditures relative to other countries. (This is what you’re saying, right?) I would guess that our aging population has played a role recently in that they consume a disproportionate amount of prescription drugs, and the ‘let Big Pharma price gouge us’ deal that Bush made is consuming an inordinate amount of health dollars. Also, HC inflation appears to have accelerated in 1980, and I would also guess that this is when a certain someone’s favorite president *ahem* began his push to privatize and deregulate. (Is this when the conversion of the Blue Cross/Blue Shields from nonprofit to for-profit entities took off in earnest, I wonder?)

There is also the thoroughly under-analysed issue of private providers. NPR’s Terry Gross summarized one aspect of financial analyst Josh Kosman’s important look of the pitfalls of equity financing this way:

(Emphasis added.) I strongly suspect that hospital and nursing home costs are being driven by the need to generate revenue to cover the equity financing of these deals. (This American Life also did a couple of good shows about the neglected role provider costs play in America’s health care conundrum, but I don’t have exact links at hand.)

I don’t think we should accept Republican framing in discussing this issue (i.e. ‘you have to choose between health care and schools!’). We could afford a great deal of the anticipated additional health care needs of our aging population by switching to single payer. A clear majority of Americans also favors increasing taxes on the rich, so the ultimate additional cost burden on everyone else may be fairly modest. (They’ll be paying more in taxes but would no longer have to pay for private health care insurance.)

But I think we’re basically in agreement about what should be done, Amp.

barring some truly enormous increase in the amount of taxes Americans are willing to pay — the costs of medicare et al are going to increasingly crowd out other things that I think we should also be spending money on, like infrastructure investment and schools.

So what’s wrong with an increase in the amount of taxes Americans pay? People in first world countries pay high taxes and seem to still have money left over to buy cell phones, BMWs, and long vacations in some of the nicer third world countries like the US. Of course, most of them also don’t waste their tax money on aggressive wars, so a few tactical spending cuts could be useful too.

I agree that the US medical care system is extraordinarily inefficient and needs an overhaul from the ground up. The current model of private insurance only is ridiculously inefficient and leads to poorer outcomes. Not to mention the fact that insurers seem to spend half their time trying to avoid paying perfectly legitimate claims and otherwise acting sleazy. You’re better off with medicare or medicaid a lot of the time. Why not put everyone on the same plan as senators have? They seem to do ok.

I also think that an investment in health care efficacy research could be quite a cost saver in the long run, i.e. finding out when an MRI is actually going to help someone with lower back pain and when it’s a waste of time, money, and anxiety could reduce costs without compromising care. But it would require the initial investment of money to research the question.

Ballgame writes:

I agree with this.

I’m not saying we should expect or want zero health care inflation (as I said, I agree entirely with Charles’ comment). However, our health care inflation doesn’t seem to be driven primarily by aging, and it’s at a level that can’t be sustained over the long run.

I’ve responded to other aspects of Ballgame’s comment in a new post.