In comments, Brandon Berg wrote:

In comments, Brandon Berg wrote:

Which, really, is why leftists aren’t so big on federalism. The left-wing program can’t work without the ability to bleed high-yield taxpayers. And if said taxpayers are free to just pack up and move to another state, that throws a spanner in the works.

Brandon then speculated about the nefarious motives of the “leftist” members of the Supreme Court, who in his view apparently sit around twirling lengthy mustaches while stroking white cats in their laps and rereading well-thumbed copies of Das Kapital.

Ron F seemingly agreed with Brandon, writing:

I’m told that this happened in California. Something like 200,000 people were paying 1/2 the taxes, so about 1/2 of them just packed up and left (or moved their money). I’m going strictly from memory here, so I imagine my numbers are off. I do believe that overall the latest Census has shown high-tax states are losing population share relative to low-tax states.

Ron’s California numbers aren’t merely off; they seem to be the opposite of true. From the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities:

…an analysis by the California Budget Project found that the number of high-income households in that state has grown substantially during periods in which higher top income tax rates were in effect. According to CBP’s findings, “the number of California’s joint personal income tax filers with incomes of $200,000 or more rose by 33.4 percent between 1991 and 1995 — a period in which California temporarily imposed 10 percent and 11 percent tax rates on high income earners.” More recently, California enacted a 1 percentage point increase on income over $1 million. The tax generated new revenue totaling about $1.5 billion in fiscal year 2008 alone. Much like the pattern observed following the tax increases of the early 1990s, the CBP analysis showed the number of taxpayers with incomes over $1 million increased — by 37.8 percent from 2004 to 2006.

It’s not that rich people are drawn to high tax areas; on the contrary, I’m sure that at the margins there are a few rich people (and non-rich people) who move here or there in search of lower taxes. But it’s simply not true that large numbers of rich people — or anyone — are choosing where to live based on tax rates.

A forthcoming study by Cristobal Young and Charles Varner in National Tax Journal (( National Tax Journal, June 2011, 64 (2), MILLIONAIRE MIGRATION AND STATE TAXATION OF TOP INCOMES: EVIDENCE FROM A NATURAL EXPERIMENT. Cristobal Young and Charles Varner. Pdf link. )) examined this question by looking at what actually happened when New Jersey raised taxes on its wealthiest residents.

Drawing on the NJ-1040 microdata — a near census of top income earners — this study examines the impact of a new progressive state income tax. Do progressive state income taxes cause tax flight among the wealthy? The New Jersey millionaire tax experiment offers a potent testing ground, given the magnitude of the policy change and the relative ease of relocating to different state tax regime without leaving the New York or Philadelphia metropolitan areas.

Using a difference-in-difference estimator, we find minimal effect of the new tax on the migration of millionaires. Using the 95–99th percentiles of the income distribution as a “non-taxed” control group, we find that the 99th percentile (those subject to the new tax) show much the same trends in migration patterns over time. There are small subsets of the millionaire population that are more sensitive to state taxation. Nonetheless, the broad conclusion holds even when looking at the richest 0.1 percent of households.

These findings mesh well with existing research showing that the migration response to

marginal tax policy changes is generally quite small.

Young and Varner did find that a small number of wealthy people left New Jersey as a result of the tax; but New Jersey gained far more revenue from higher taxes than it lost to migration.

As Young and Verner note, their research matches the findings of many other studies. ((Of course, if a state raised their taxes high enough — let’s say, a 90% tax rate on all income over $100,000 — I’d expect that to convince many wealthy taxpayers to move across state lines. But in the real world, taxes are nowhere near that level.))

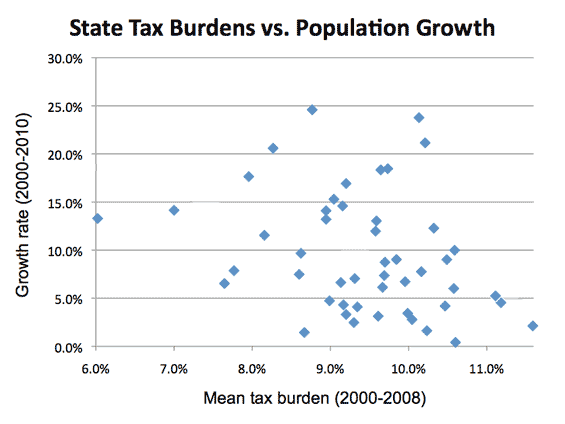

So what about that Census data? Ron is quite right that states with higher taxes have had less population growth than states with low taxes (although nearly all states had some population growth) — although the correlation isn’t the strongest I’ve ever seen. Conservatives pushing this argument have used a graph with a “best fit” line to make their case, which is perfectly legitimate; but it’s instructive to see the same graph without the best fit line:

There’s correlation there, but not an open-and-shut case.

More importantly correlation is not causation; is it really taxes driving migration patterns, or do other economic aspects — like the cost of buying or renting a house — matter more? Or do non-economic factors matter, such as more retirees moving to warmer southern states? A reasonable study would have to account for these factors. What conservatives have is not reliable evidence, but a loose correlation combined with wistful wishful thinking.

Wishful thinking, not wistful, unless the conservatives are looking back through their college yearbooks and sighing over vanished love.

Re: your second footnote: I don’t actually think that’s true.

I don’t think a naive analysis of taxes vs. “pedestrian voting” (moving out) will be very illuminating without extensive correction for confounding factors.

I suspect that there IS a strong correlation, however, between perceived value received from government and happiness/unhappiness with one’s place in a state.

If I was living in Mississippi, I would be paying a significantly lower rate of taxation than I pay in Colorado. But – having spent a lot of time there – I would also be significantly less satisfied with the government I was receiving for my money. (Bedford Forrest license plates, my ass.) I’d rather live here and pay more and have a better government.

Tax Bill Gates 90% and spend the money on parties for state bureaucrats, he’s probably not too pleased. Tax Bill Gates 90% and spend the money kissing his ass and following his policy preferences, he may be perfectly satisfied.

Wow, if I tried to show ANY sort of best-fit line on that last graph to the man who taught me statistics, I would probably not end up with the Master’s I’m working on. Maybe it’s because I’m not in economics, but to say the correlation is loose is, well, loose.

Since I think everyone should be able to interpret things like this, here is a really good explanation of how best-fit lines work that should give everyone an idea of why the graph above does not.

I think there are a number of factors, but I do not think you can necessarily rank them. Looking at the data on the link, one thing immediately stood out. The top two states for tax favorability were Alaska and Nevada, respectively. Nevada had a much greater increase in population and it is easy to guess why (hint: the weather and Alaska is not contiguous with the lower 48). Just as a matter of common sense, there will be other factors that affect migration, but I do not think you can come up with a metric to account for all of them.

You can also look at people’s lack of mobility in employment. Some professionals (lawyers, for example) face a difficulty in moving because of licensing, while others (electricians, perhaps) can move more easily, and even others (writers, or independent cartoonists) maybe be able to move without any such obstacles.

One thing this article does not appear to account for is corporate mobility. Companies that expand can certainly take tax rates into account when deciding to open a plant in a different state (or country, for that matter). Companies are more immune to some of the other considerations that individuals face. These decisions can also drive growth rates, but not necessarily in a clear-cut way That is to say: if a company decides to expand and open a plant in a lower tax state, it may pick Texas or South Dakota, but it can’t pick BOTH; so its decision (which may also take into account climate, geography, median income rates, minimum wage laws, the educational levels of the citizens of the state, etc.) may drive population growth in one state, while a similarly tax favorable state does not grow as much.

-Jut

@thewhatifgirl

You are correct that the given scatterplot does not show a linear correlation. I would like to point out that the site you linked to is incorrect. One does not need an r value of 0.990 to get 99% confidence that the slope is not zero. According to Brase and Brase Understandable Statistics, the t statistic is (r*sqrt(n-2))/sqrt(1-r^2) with n-2 degrees of freedom (If I remeber correctly, the book is at the office.). Getting an r^2=0.990 means that the SSR is 99% of the total variation SST.