Whenever I teach ENG 105, I always begin with the same lesson, the point of which is to get students thinking about how much they know about the grammar of American English without even realizing they know it. I start by putting the following sentence on the board:

The boy hit the dog with a fish.

Then I ask them to tell me how many different meanings they can find in that sentence. Eventually, usually pretty quickly, someone will raise their hand and explain that either the boy is holding the fish and using it to hit the dog, or the dog has a fish in its mouth when the boy hits it. How, I ask, is that possible? Not just that one string of words can have two different meaning, but that someone who has never formally studied grammar at the college level is able to find those two meanings with relatively little difficulty. Then I make the sentence a little more complicated:

The boy hit the dog with a fish in a box.

We spend some time puzzling out the different ways of reading that one, and then I put some other ambiguous sentences on the board:

- Visiting relatives can be boring.

- I gave her cat food.

- Did you see the girl with the telescope?

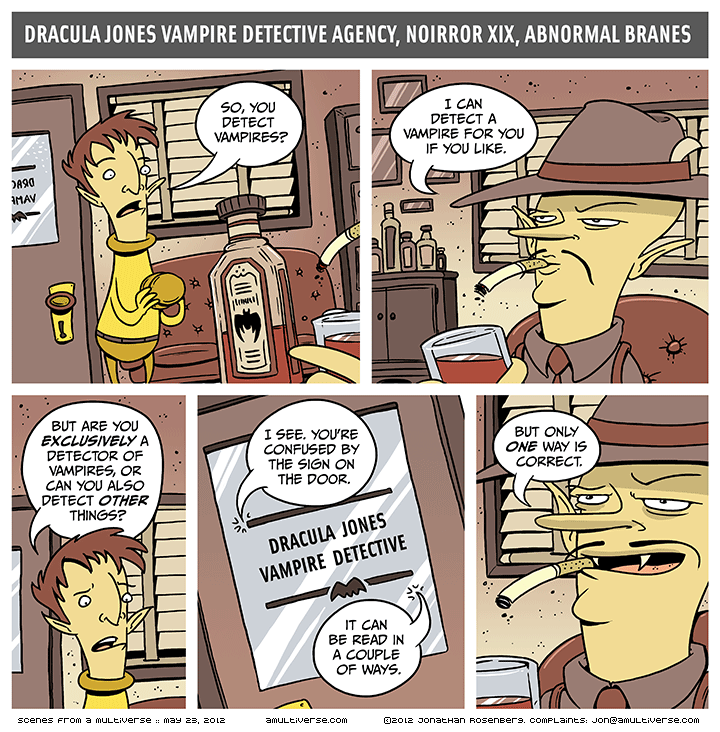

- Prostitutes Appeal to Pope.

The last one is an actual headline I copied down from somewhere a very long time ago, but even though it is a slightly different kind of ambiguity because it has to do not with the syntactical structure of the sentence per se, but with the two different meanings of appeal as a verb, it helps to make the point that my students (and remember I am talking in this series about native speakers) all have an unarticulated understanding of the underlying semantic and syntactic structure of English. If they didn’t, they would not be able to find the ambiguities.

Next, to make this point from a slightly different direction, I put on the board some sentences like these:

- The plittle gliffered the lokain.

- The foreign lankert is graffingly tired of too much voomin.

When I ask them what these sentences mean, it takes a little longer, but someone will eventually explain that, in the first instance, something called a plittle performed an action known as to gliffer on something called a lokain and that, in the second sentence, lankert, which comes from another country, has had enough of whatever a voomin is. Again, I ask my students how it is possible that they can know this, despite the fact the words most central to the sentences meaning are clearly not English. This then leads into a discussion of what linguists call the surface structure of a language, which more or less corresponds to the part of the language we see when we read or hear when we listen, and, again, the point is to illustrate for my students their own pre-existing knowledge of the subject they have taken my class to study.

Finally, just for fun, though its actually a serious kind of fun, I ask my students to tell me whether they wait in line or on line, why we (for most of us in New York anyway) get in a car but on a train, plane, or bus. Then I will ask them to tell me whether they are in school or at school, in class or at class, and to see if they can figure out the circumstances under which they would choose one preposition over the other. As they struggle to figure that out—and it doesnt really matter to me whether or not they come to any firm conclusions—I point out, again, that they would not even be able to have the discussion if they did know quite a bit about how to use their native language properly.

In the past, my goal for this lecture has been simply to pique their interest, to get them to see grammar as a subject they can own, and I use that idea to segue into the value of learning to diagram sentences as an intellectual exercise. This semester, though, I need to use this lecture, which I am loathe to change if only because it works so well, to introduce the idea that learning grammar (and we will be doing some diagramming in connection with that) will, as Nora Bacon puts it in her chapter called Clause Structure, help my students gain…control over written language [by enabling them] to read the work of other writers with a discriminating eye, which she defines as the ability to look at sentences analytically, seeing what the parts are and how they fit together (The Well-Crafted Sentence 18). ((I should say that I am skipping over the fact that, if past experience holds true, I will have to spend a weeks worth of class reviewing the parts of speech.)) Bacon begins with clause structure, which makes eminent sense, not just because it allows her to cover the three kinds of verbs (transitive, intransitive, and linking), but also because it allows her to make the point that good writers are good in large measure because of their skill in manipulating clauses. She offers these two sentences as an example of how important the conscious placement of clauses can be:

- Even though I want a piece of cherry pie, I’m committed to my diet.

- Even though I’m committed to my diet, I want a piece of cherry pie. (30)

One of these sentences represents someone who is planning to stick to her or his diet; the other represents someone who is planning not to. While my students will almost certainly be able to tell intuitively which is which, I am looking forward to finding out whether and to what degree teaching them about adverbial clauses will help them figure out how to translate that intuitive knowledge into a conscious writing practice.

Cross posted on my blog.

“Prostitutes Appeal to Pope” is from “Squad Helps Dog Bite Victim”, a book of less-than-clear newspaper headlines and such. It and its sequel, “Red Tape Holds Up New Bridge”, are also used by neuropsychologists and speech therapists (well, at least one speech therapist. She borrowed my copy).

I can’t tell anything about a person’s behavior from those two sentences, because they are not about behavior. They are about motives. The first sentence emphasizes that one desire won’t overcome the other, and the second sentence emphasizes that one desire doesn’t preclude having the other. The choice of action is still up in the air. In both cases the person could have pie and still be committed to a diet.

Personally I object to using food issues as an example, and holding out being committed to a diet that doesn’t include pie as a possible good choice as being a morally superior position.

Kai Jones–

I think you’re reading of the two sentences is more accurate than Bacon’s, which I pretty much parroted without saying so in that last paragraph. Thanks. And I hadn’t thought about the politics of using food as an example. Thanks for that as well.

Literally, neither sentence specifies action. But I definitely read the sentences to provide the cues suggested by the author. This illustrates the weight I give to the end of sentences relative to the weight I give to the beginning. And this dynamic triggers two observations:

1. Most drafting guides urge me to avoid passive voice, and instead to use the active format: Subject does verb to object. Yet typically the object is not the most important part of the sentence. Consequently I often reject this advice. As I stand at the podium with the envelope, I prefer to say, “And this year’s Grammar Award has been won by Richard Jeffrey Newman!” rather than “Richard Jeffrey Newman won this year’s Grammar Award!” – passive voice be damned.

2. Recall Conjunction Junction — a discussion of AND, BUT, and OR? If you studied formal logic, you will recall that “I plan to buy the next book by Amp AND by Grace” is true only if I plan to buy both books. (No pressure, though.) The statement “I plan to buy the next book by Amp OR by Grace” is true if I plan to buy either book. Note, however, that there is no logic definition for BUT. As a matter of logic, BUT is the same as AND.

Yet in usage, we distinguish between the words BUT and AND all the time. In particular, there are many contexts in which the word BUT signals that the end of the sentence is all that matters, and the first part is not only unimportant but perhaps even insincere. When I hear, “I love you, BUT I’m not in love with you,” I doubt the “I love you” part. When I hear “You’re welcome to stay, BUT you’ll need to sleep in the garage,” I doubt the “You’re welcome” part.

One way to minimize this dynamic is to use the word AND in place of BUT. When I hear “I love you AND I’m not in love with you,” it seems to shift some of the emphasis back to the first part of the sentence. Trust me; I’ve had a lot of experience with this one.

Oh, I really enjoy discussions like this. :) Actually, this is something that gets discussed by Judy Swan when she does science writing seminars–I don’t want to mangle her message, but basically, she spends a lot of time talking about how people place reading emphasis when two clauses are put next to each other like that, how order and conjunction choice and the relative wordiness of the clauses matter. It’s a useful exercise, not least because in many cases there’s disagreement even among native speakers on where the emphasis lies.

The difference between dedication and commitment:

Have you ever had ham and eggs?

The chicken was dedicated. The pig was committed.

Ever since someone told me that one, I’ve noticed that people, especially politicians, like to use “committed” to emphasize the strength of their actual dedication. Also, I have handled “committed” with great care, using it only when describing something past the point of no return.

Grace

nobody.really, in my experience the only people who try to navigate a situation by distinguishing between “loving” and “being in love” are shallow people who think that a wholesome relationship will always be unadulterated joy. They are like an eater who demands that wholesome food always taste sweet. They get a lot of sugar rushes, and a lot of sugar crashes, and at the end they don’t have the stamina for the real deal.

It sounds like you may have had a similar experience, and I’m sorry to hear it.

Grace

I would have dearly loved to have taken this class; it sounds as if it would have been so much fun!

I remember reading a headline in the local paper when I was young: it said, Red Banker Arrested, and I was thrilled. Imagine that! A Communist banker arrested in the neighboring small town!

Er, no. It was much more mundane than that. That small town, in fact, was the town of Red Bank, and it was merely a local denizen who’d been apprehended doing something I don’t even remember. From international intrigue to misinterpretation in one crashing moment of misinterpretation.