This is a repost; I originally posted it about five years ago, and Jeff’s post today reminded me of it.

This is a repost; I originally posted it about five years ago, and Jeff’s post today reminded me of it.

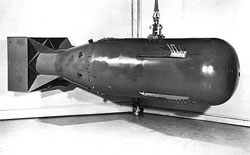

Historian Gar Alperovitz, among others, has argued that US leaders knew they could have gotten a surrender from Japan, without dropping the bombs. There are a number of impressive quotes in support of this idea, like….

“Experts continue to disagree on some issues, but critical questions have been answered. The consensus among scholars is that the bomb was not needed to avoid an invasion of Japan and to end the war within a relatively short time. It is clear that alternatives to the bomb existed and that Truman and his advisers knew it.” -J. Samuel Walker, chief historian of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

“It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender.” -Admiral William D. Leahy, Former Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

“…Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary […and] no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at this very moment, seeking a way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face.’ ” -General Dwight D. Eisenhower

“P.M. [Churchill} & I ate alone. Discussed Manhattan (it is a success). Decided to tell Stalin about it. Stalin had told P.M. of telegram from Jap Emperor asking for peace.” -President Harry S. Truman, Diary Entry, July 18, 1945.

For a summary of the most radical “dropping the bomb was unnecessary” view held by any respectable historian, check out Gar Alperovitz’s 1995 “Foreign Policy” article. I’m not sure that I buy all of Alperovitz’s conclusions, but that the war could have been ended without either the A-Bomb or a full invasion of Japan is a fairly well-supported view. (Of course, some right-wing historians – notably Robert Maddox – disagree. But theirs is not the mainstream view.)

The issue wasn’t if the Japanese were prepared to surrender – but if they were prepared for unconditional surrender. Then and now, many experts believe that the Japanese would have surrendered if they had assurance that they would be able to retain their Emperor in some capacity. As Japanese Prime Minister Suzuki announced on August 9, 1945 (three days after Hiroshima, the day Nagasaki was bombed) “Should the Emperor system be abolished, they [the Japanese people] would lose all reason for existence. ‘Unconditional surrender’, therefore, means death to the hundred million: it leaves us no choice but to go on fighting to the last man.”

What Americans usually forget is that the Japanese didn’t surrender after August 5, 1945; nor after August 9. On the contrary, Japanese hawks were quite prepared to fight to the death after the dropping of the bombs; that the US so vastly out-powered them only added to the romantic fatalism driving their pro-war views.

So what did bring about the Japanese surrender? On August 11th, the Americans finally gave the Japanese Emperor and doves what they had been waiting for: surrender terms which said “the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied powers.” This amounted to an explicit statement that the Emperor would not be removed from office. After a few days of studying the terms, on August 14 the Emperor asked the Cabinet to accept the surrender offer; the Cabinet unanimously agreed to surrender that same day.

To the Japanese hawks, this was the one request for peace that could not be turned down. The Emperor was considered a god, after all. It was the Emperor’s request – not the two atomic bombs – that convinced the hawks in the Japanese Cabinet to surrender.

For further reading on the Japanese surrender, I recommend Doug Long’s essay Hiroshima: Was it Necessery?, as well as the Gar Alperovitz essay I mentioned above. Also, check out the Slactivist’s post on Hiroshima.

Although I think it may be true for a lot of the fanaticized Japanese military, I’ve been told again and again by my own family — my mother and grandmother, both of whom lived through the war — that the average citizen of Japan in 1945 did not believe that the Emperor was a deity, that there wasn’t a whole lot of chance that every single citizen of Japan was going to pick up sharpened bamboo sticks and throw themselves suicidally at infantry in case of a land invasion.

My family might be a little biased, seeing as they had a history of being involved in anti-war activism in Japan, my grandfather arrested by the military police for conspiracy, etc. However, I think they’re a little more grounded in reality than Western notions of an entire nation full of fanatical, samurai-spirited suicidal warriors who worship a human demigod. Talk about silly stereotypes. What you have to remember is that before the late 19th century, few average Japanese people even knew who the current Emperor was. The whole Imperial system was an obscure relic with little if any influence, and wasn’t even hooked into Shinto observances. The oligarchy that took over the country propped the Emperor up as a sort of figurehead and built a religion around him — there was no long tradition, at least not in the last 1000 years beforehand, of everyone worshipping or obeying the Emperor.

All of this is a little besides the point, I guess, because the real point is the Japanese military, which was running things, and really had succeeded in brainwashing a lot of soldiers. I don’t know if I really believe that all or even most of the top brass were really uncynical believers in the state religion, either. Sure, there’s a lot of fanaticism and devotion, even in the right wing today, but they often remind me more of a mixture of Ann Coulter and Fred Phelps — either batshit insane by any average standard, or cynical manipulators.

That still doesn’t mean that they would have necessarily surrendered or not surrendered. But I think the arguments about how a surrender of the Japanese military could have been effected are more plausible if they don’t include all these ideas about how every Japanese person worshipped the Emperor like a god and was willing to fall on their sword.

One theory I have read is that the bomb on Hiroshima was dropped as a way to deter the Soviet Union after the war was finished.

Holly, before the late 19th century, few Japanese knew who the emperor was because he was a figurehead with no power. The Meiji Restoration in 1868 that changed that and the emperors became, if not unchallenged rulers, significant power centers in their own right. It is probably true that Joe Japan didn’t think the emperor was literally a deity, but it’s equally true that loyalty to the emperor was a very strong motivating factor for many, many Japanese; he was the glue holding the political system together.

Your peace activist relatives, by the way, were incredibly brave people. Violence against anti-war types was extremely common during the militant phase of Japanese history, and killing “doves” was an accepted tactic. One of the reasons for the delay in the surrender, in fact, was the very real concern on the part of the dove faction in the Japanese government that they would personally be killed, and/or that even the emperor would be killed, by the pro-war/pro-imperialism faction which was usually ascendant.

I don’t think we have to believe in the popular acceptance of Hirohito as a deity in order to believe that the resistance to a land invasion would have been heroic and exceptionally bloody. Maybe that isn’t true – although I see no reason to believe it isn’t true – but it is certain that the US and British high commands were convinced that it was true.

The intricacies of the politics inside the Japanese cabinet and the various ministers who held the power along with the emperor are pretty mind-boggling. I doubt that any of us lay civilians are going to be able to have an informed opinion about what was the actual triggering factor in the surrender; the idea that the Emperor’s survival was a key factor is certainly plausible but probably not sufficient. It was complicated.

One could make a case for the Hiroshima bomb being necessary or, at least, good on the balance. (I don’t believe it but acknowledge the possibility of a reasonable person making the argument.) But the Nagasaki bomb? Can that reasonably be called anything other than an act of evil?

Dianne beat me to it. I can see the arguments for Hiroshima, but Nagasaki never made much sense to me.

But OT: I think that Hiroshima may have been justified as much as anything in that war was justified. The concept was definitely that one’s own country’s existence/lives were worth an amount immeasurably more than one’s enemies.

So while more people probably died in Hiroshima than would have died on both sides absent Hiroshima, it is likely that the U.S. deaths counted alone were probably reduced by Hiroshima, or so I have read. From a wartime perspective that is/was the primary concern. (and still is, perhaps, even now, since war is still war. How many Iraqis would GWB trade for a US soldier? How many Israeli soldiers would a Hamas member kill to preserve the life of a comrade in arms? How many hamas members would Israel kill to save the life of one of their soldiers? and so on.)

Holly, point well taken; I’ve crossed out the bit referring to the Emperor’s godhood. Thanks.

So… How is this not Monday morning quarterbacking?

None of us here have ever sent hundreds of thousands of boys off to die, nor have we caused hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths over years of war. We’ve had sixty-odd years to reflect on the decision to drop the bombs. We know how Japanese citizens reacted to the Allied occupation, and we have a (better) idea of how they would have reacted to an invasion.

So, by all means, try to figure out what might have happened had the bombs not been dropped. But taking that information and using it to decide whether dropping the bombs was “necessary”, or deciding what one person or another should or should not have done, seems particularly useless.

None of us here have ever sent hundreds of thousands of boys off to die, nor have we caused hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths over years of war.

My first reaction to this comment was, “Unless George Bush happens to be reading this blog.”

My second reaction was that we* kind of have: The US is a representative democracy. So what the government does, we (the voters) do. By voting for the person we vote for or failing to vote against the person who we don’t want in power, by protesting or supporting policy decisions, by expressing support or lack of support in polls, we influence policy.

Maybe the majority of US-Americans weren’t thrilled about the Iraq War. But they didn’t care that much or it wouldn’t have happened. No politician is going to make the voters REALLY mad. Consider, for example, that there has never been a famine in a democracy. That’s because the politicians find ways to make sure that the voters get food. Because if they don’t they’ll be in big trouble and they know it. If the majority of US-Americans wanted out of Iraq, on the level that we want to eat or even on the level that we want our cars and A/C, the war would end. So, yes, we have sent young people off to another country to die. Yes, we are killing civilians even as we type.

Neither McCain nor Obama has ruled out the use of force, including nukes, in Iran. McCain is downright eager for it. I expect we’ll be killing more civilians in the near future. Unless we really don’t want to.

*Where “we” are the voters of the US. Obviously, people who are not citizens of the US or are otherwise disqualified from voting aren’t being addressed in the above comment.

Dianne is quite right. We the people are the final arbiter of what our society does or doesn’t do, and it’s entirely meet for us to sit in judgment on our leaders, even decades after the event. If nothing else, it’s healthy for today’s leaders to realize that their decisions will be scrutinized into the dirt; they’ll try to get away with less.

At the same time, Bjartmarr’s point is an apt one. It’s Monday morning quarterbacking to decide that long-gone decisions should have been made differently, based on the standards of people with leisure for analysis and the advantage of getting to see fifty years of events after the decision in question. So our post-mortems should have some humility in them, and some awareness of our own lack of time pressure and responsibility for consequences in re-running the scenario.

By voting for the person we vote for or failing to vote against the person who we don’t want in power…

Heh. How can voting for somebody not be voting against a person that we don’t want in power?

As I meant to say earlier, but failed to because I got distracted on general Weltschmerz, is that, yes, examining the decision to bomb Hiroshima is Monday morning quarterbacking. However, we, the voters, are the coaches. We need to know what happened and decide how we feel about it because we’re about to declare who the next person to control the world’s largest arsenal of nuclear weapons is.

How can voting for somebody not be voting against a person that we don’t want in power?

What I meant to convey was the idea that failing to vote for any candidate is a political act as well. It may be meant to mean “none of the above” but the effective statement is “either of the above.”

The application of nuclear weapons, in my opinion, was almost inevitable. It’s a “better weapon”, just like every “better weapon” ever developed. Of course it would be used. The only way it might not have been inevitable was if the development of nuclear power occurred after the development of World Peace.

I sort of consider it a kind of blessing that the experimental use of nuclear weapons occured in the earliest days of nuclear power when the megaton range was at it’s smallest. Had we refrained from using them against Japan, would the lessons we learned about the consequences of a nuclear conflict merely have been delayed so that later some bigger and badder nuke, during a war with less moral justification, got to be the “first”?

My Uncle was a Marine at 17 who fought at Iowa Jima. He is in the US Armed Forces Retirement home in DC. Has lost both legs. His viewpoint is very different from those who have had the luxury of being far removed from the horrors of the War in the Pacific in WW2. Revisionist Historians are ignoring the plans to invade Japan with 10 Million Americans.

Those who were in the thick of it have a very different vantage point.

Dianne,

The Nagasaki bomb was necessary because atom bombing Hiroshima by itself was not sufficient to prompt Japan to surrender. The Japanese had to be convinced of the futility of continuing the war, that continuing their war of aggression would result in their annihilation. You might consider how evil it was for the Japanese to be so committed to war.

Even after the second atom bomb, the Japanese military remained unmoved from its position to bleed the Allies to gain the best surrender terms. As members of Hirohito’s cabinet have said, the shock of the atom bombs is what convinced the Emperor to call for surrender.

When you argue against the atom bombs, you are implicitly arguing for a conventional war which would have been far more deadly by an order of magnitude. That is an inferior moral choice which you should abandon.

Here is Oliver Kamm in the Guardian, arguing against Alperovitz’s view.

Most, if not all, of the arguments in favor of dropping the atomic bombs can be characterized as variations of either “the ends justify the means” or “two wrongs make a right”. Whether or not these are reasonable justification has already been discussed in great depth. But I have the following question. If we accept the idea that the deliberate killing of noncombatants is moral and just in order to achieve a worthwhile result, or to avenge a wrong, what prevents other parties (perhaps even our enemies) from using these same arguments to justify the deliberate killing of American noncombatants? For example, if the concept of self-defense is to have any meaning at all, the American Indians had the moral right to fight the invaders and conquerors of their land by all means available. If they had the means, would it have been morally acceptable for them to drop an atomic bomb on Washington or New York? Many Americans, particularly Southerners, regard Sherman’s burning of Atlanta and March to Savannah as war crimes. But wasn’t it the functional equivalent of the firebombing of Tokyo and the nuking of Hiroshima/Nagasaki, with many of the same justifying arguments? Cripple their economy, demoralize their population, shorten the war, save Union lives, and punish them for their evil deeds (slavery, Fort Sumter, Andersonville, and secession).

Another explanation for the Japanese surrender occurring when it did comes from Ward Wilson, here summarized by Freeman Dyson at http://www.edge.org/q2008/q08_2.html

“3. On the morning of August 9, Soviet troops invaded Manchuria. Six hours after hearing this news, the Supreme Council was in session. News of the Nagasaki bombing, which happened the same morning, only reached the Council after the session started.

“4. The August 9 session of the Supreme Council resulted in the decision to surrender.

“5. The Emperor, in his rescript to the military forces ordering their surrender, does not mention the nuclear bombs but emphasizes the historical analogy between the situation in 1945 and the situation at the end of the Sino-Japanese war in 1895.”

In other words, Hiroshima was not sufficient to convince the Japanese to surrender to the US – but the prospect of an invasion by the Russians was.

The question then becomes: why did the US drop two bombs before offering Japanese the terms they wanted? Was it intended to scare Stalin, more than the Japanese?

Of course, we weren’t there, and our viewpoint is distorted by hindsight and other factors. I’m prepared to accept that the bombing of Hiroshima was intended as a less bloody alternative to an invasion… but when that failed to sway the Japanese, I find it difficult to imagine why they thought that bombing Nagasaki would have a different result.