A discussion in comments, combined with waking up early and having some time to pass before Kevin picks me up to go to work, led me to read up a bit on California’s budget.

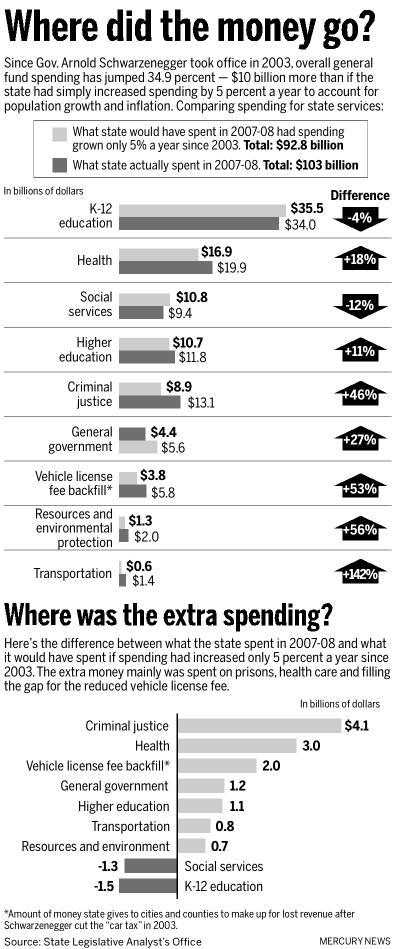

The most useful graphic comes from the San Jose Mercury News.

So the largest chunks of California’s budget woes are the justice system, the health care system, and a tax cut.

Another big chunk — not included in the Mercury’s graphic — is that the recession has lowered both sales tax and income tax revenues, as people earn and spend less. California has, both through elected officials and through voter initiatives, made major cuts in the relatively recession-proof taxes (car taxes, property taxes). Meanwhile, increases in people needing aid means that spending rises in a recession. As a result, California’s budget is hit harder by a recession than most states.

The article accompanying the graphic is very worth reading.

For more background on how this situation came to pass, I’d recommend reading this blog synopsis of a presentation by Professor Scott Frisch. The blog also links to Professor Frisch’s powerpoint slides, which are worth browsing through.

From the Mercury article:

So looking at the past five years, where did that “extra” $10.2 billion of state spending above the rate of inflation and population growth go? The Mercury News found:

# The state prison system received the biggest share, about $4.1 billion of it. Corrections spending has increased fivefold since 1994. At $13 billion last year, it now exceeds spending on higher education. Tough laws and voter-approved ballot measures have increased the prison population 82 percent over the past 20 years. Meanwhile, former Gov. Gray Davis gave the powerful prison guards union a 30 percent raise from 2003 to 2008, increasing payroll costs.

# Public health spending — mostly Medi-Cal, the state program for the poor — received $2.9 billion above the rate of inflation and population growth. Part of that spike is due to an aging population; part is rising national health care costs. But state lawmakers also expanded Medi-Cal eligibility among children and low-income women a decade ago, increasing caseloads.

# Schwarzenegger’s first act as governor, signing an executive order to cut the vehicle license fee by two-thirds, blew a large hole in the state budget. It saved the average motorist about $200 a year but would have devastated the cities and counties that had been receiving the money. So Schwarzenegger agreed to repay them every year with state funds. That promise now costs the state $6 billion a year, or $2 billion more than the rate of inflation and population growth since early 2003.

Most Democrats in California would agree to balancing this mess with a combination of service cuts and tax increases. Unfortunately, proposition 13 requires two-thirds of the legislature to agree before ever raising taxes, and the Republican minority will not agree to any tax increases at all (although most of them support both spending increases — not all “tough on crime” measures are voter initiatives — and tax cuts).

Look again at Schwarzenegger’s executive order cutting taxes. Schwarzenegger expressly structured this so that no spending cuts would balance his tax cut. This is a textbook example of Republican/conservative fecklessness and irresponsibility — the difficult, grown-up work of paying for tax cuts — either by raising revenues elsewhere, or by making spending cuts — is always deferred.

Which relates to a larger problem: Americans want government services, but they don’t want to pay for them. This basic tendency is made worse in California by the voter initiative system combined with the two-thirds requirement, but it’s a problem throughout the United States.

And our politics makes the problem worse — and this is as true nationally as it is in California.

In California, passing a budget or raising taxes requires a two-thirds majority in both the state’s Assembly and its Senate. That need not pose a problem, at least in theory. The state has labored under that restriction for a long time, and handled it with fair grace. But as the historian Louis Warren argues, the vicious political polarization that’s emerged in modern times has made compromise more difficult.

All of this, however, has been visible for a long time. Polarization isn’t a new story, nor were California’s budget problems and constitutional handicap. Yet the state let its political dysfunctions go unaddressed. Most assumed that the legislature’s bickering would be cast aside in the face of an emergency. But the intransigence of California’s legislators has not softened despite the spiraling unemployment, massive deficits and absence of buoyant growth on the horizon. Quite the opposite, in fact. The minority party spied opportunity in fiscal collapse. If the majority failed to govern the state, then the voters would turn on them, or so the theory went.

That raises a troubling question: What happens when one of the two major parties does not see a political upside in solving problems and has the power to keep those problems from being solved?

If all this is sounding familiar, that’s because it is. Congress doesn’t need a two-thirds majority to get anything done. It needs a three-fifths majority, but that’s not usually available, either. Ever since Newt Gingrich partnered with Bob Dole to retake the Congress atop a successful strategy of relentless and effective obstructionism, Congress has been virtually incapable of doing anything difficult because the minority party will either block it or run against it, or both.

I understand what you and the Slate writer are saying (writing, rather), but I don’t think that the stimulus polls are necessarily evidence of hypocrisy. It’s safe to assume that those who opposed the stimulus also thought that too much was being spent. The supposedly hypocritical 20% of the population could just be moderates who supported it at first and then backed out later on or supported it, but thought less money should have been spent on it.

However, I am sympathetic to the claim that Americans want government spending but don’t want to pay for it. Sarah Palin and other lamestream conservatives are good examples. They want to lower taxes, but have no problem spending gigadollars fighting wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, et al. This is one of the reasons why even though I am a libertarian, I am not a Tea Party participant. It’s kind of hard to cut government and taxes when you want to expand the section of the government that takes up a quarter of the federal budget.

And of course my mother-in-law — whose involuntary furlough days are preventing her from making rent — is working for the fucking justice system. Not even the prisons can afford to run.

Tracing the origin of an idea is like tracing the origin of a species: you can generally find another predecessor. That said, I’ve been pondering the origins of this “let-it-burn,” anti-establishment ethic that seems so rampant in the Tea Party Movement.

In particular, I can’t help but see parallels to the 60s counterculture. “Tune it; turn on; drop out” is a somewhat more introverted way of expressing similar ideas. And now I’m having a new appreciation for why voters might find this ethic so alarming that they’d do anything – even vote for Nixon – to preserve society.

Traditionally I’ve blamed democracy’s woes on back-room deals and “elites.” Doubtless I still can. Yet today’s technology make these forces ever weaker because Congressmen have ever less room to consider dynamics other than what will help them get elected. In this sense, they are ever MORE responsive to voters. Alas, this means that they must shelve their years of experience and present knowledge – relying on that would be elitist, see? – and instead defer to the opinions of a public that spends ever less time with a newspaper. This need to be wholly responsive to the demands of an ignorant, petulant public is killing democracy.

How have politicians dealt with this problem in the past? Bread and circuses: Create some dramatic side-show for the public to focus upon, thereby freeing up the rest of government to function below the public’s radar. I still subscribe to the idea that the Iraq War was created to distract the public from larger social problems – growing unemployment, mounting deficits and the failure to capture Osama Bin Laden – in an election year.

So, perhaps the solution for California and for the US is to find the least-burdensome circus for government to pursue. The moon landing was pretty good. The Olympics are nice. The OJ Trial was quite diverting. Katrina got quite a bit of attention, although it’s hard to schedule a natural disaster. But none of these topics have managed to keep domestic politics out of the headlines quite as well as a nice, long morality-ladened war.

Alas, even the current wars have not proven sufficiently distracting that people won’t realize that they’re paying more taxes. So maybe we need a still greater solution. Suggestions?

The exercise above is useful to figure out how priorities in State spending have changed and where the biggest contributors to excess spending are, but it does not show the actual amounts of excess spending. You are making an assumption that there is a natural increase in spending based on population increases and inflation. I think that’s a false assumption.

It’s not reasonable to assume that a) expenditures should increase at all, and b) if so the increase should be a function of inflation and population increases. Why should that be so? Does that represent a reasonable measure of what the budget problems are? I don’t think so.

I suggest to you that budget woes come from expenditures growning faster than income. Regardless of where the money was spent, if you spend more than you take in you have deficits and thus problems. The fact that the State’s population has increased indicates that demand for State services has increased. It doesn’t mean that there’s more resources for funding them. Where you spend money is a function of legal and social priorities. How much you spend is a function of how much you have.

Let’s say 5 million poor people that are net consumers of tax money move into the state and 1 million people that either have productive tax-revenue generating small businesses or that have at least decent paying jobs get sick of paying high taxes and move out. You have a net increase in population, a net increase in demand for tax expenditures but a net decrease in tax base and revenue. Demand is up, supply is down and the budget goes to hell.

So I would say that a better comparison for determining why California has ended up in the situation it’s in would be to compare the growth in spending with the growth in the tax revenues and the tax base. That gives you the real difference in income vs. expenditure, which in turn is the real basis for budget problems. Simply presuming that “we have more people so we should be spending more” without tracking available income is a recipe for financial default.

The theme of “People want government services but don’t want to pay for them” needs to be broken down a bit. First, by income. I suspect that a lot of the people who want increased government services CAN’T pay for them, and the people who are less enthusiastic about wanting government services are the very people who ARE expected to pay for them. So to say “people want” needs to be broken down by which people want what.

The Salon writer holds up the fact that people are against the stimulus package and yet want specific things such as increased highway maintenance as an example of contradictory expectations by the American public. But that’s too broad a brush. It’s entirely possible – and I’d say even likely – that people oppose spending on banks and car companies while favoring things like fixing roads and bridges. They associate the former with the stimulus spending a lot more than the latter, as the former has gotten way more national media attention. But you could increase the spending on the latter, cut the former and have a net cut in proposed stimulus spending while having an increase in spending on what people actually want money spent on.

I’ll agree with the main theme that people want more than they are willing to pay for. That’s human nature. But I don’t think there’s sufficient exposition into who wants what and who’s not just willing but able to pay for it for this to be a sufficient explanation into what’s going on.

thank you for this. i’m in total agreement that the 2/3 majority needed for tax increases plus the burdens imposed by our out-of-control initiative process [which brought us the 2/3 rule on budgets] have created a huge mess.

the idea of initiatives sounds very direct-democracy. but they are all backed by powerful forces, and the signature drives staffed largely by paid signature-gatherers. and here’s the thing: nobody backing or voting for an initiative is in a position to weigh the pros and cons very thoroughly, and certainly not balancing costs/benefits against every other law on the books. that is why we have a legislature: they are elected and paid to do that work.

Based on what I’ve seen so far here regarding the analysis of the restrictions put by the people on the California legislature by referenda, I’d say that the California electorate is saying:

1) Don’t raise taxes

2) Spend about 30% of the budget on these particular areas that we believe deserve priority, and

3) Cut spending in other areas so as to conform with 1).

They’ve enforced 1) and 2) via citizen initiative. The legislature has the choice of either conforming to 3), running a deficit or convincing the electorate to amend the State constitution. So far they’ve chosen to run a deficit. At some point they’re going to have to either cut spending or get the electorate to approve a Constitutional amendment. The politicians want to be able to keep spending up in order to satisfy certain interests. But my guess is that the electorate wants them to cut spending without raising taxes and would much rather have them cut spending on social services than on infrastructure or schools.

thank you for this. i’m in total agreement that the 2/3 majority needed for tax increases plus the burdens imposed by our out-of-control initiative process [which brought us the 2/3 rule on budgets] have created a huge mess.

Did the initiatives force the state to spend money it didn’t have? From what I’m seeing the initiatives control around 30% or so of spending. The legislature could have chosen to minimize spending on those areas covered by initiatives to that 30% and then cut other spending to maintain a balanced budget. It has not chosen to do so. I would fault the legislature before I’d fault the results of the initiatives. They knew they wouldn’t be able to raise taxes but chose to ignore that fact to try to keep everyone happy.

nobody backing or voting for an initiative is in a position to weigh the pros and cons very thoroughly, and certainly not balancing costs/benefits against every other law on the books. that is why we have a legislature: they are elected and paid to do that work.

This is the Jeffersonian vs. Jacksonian debate. Are legislators supposed to reflect the will of their constituents, or are they there to do as they see best regardless of what their constituents think at the moment? Yes, the legislature have at least theoretically the resources, time and ability to see the big picture and make informed judgements superior to those of their constituents. But the people are not satisfied with the outcomes, or else those initiatives wouldn’t pass. The people have a right to put constraints on their legislators, who are constantly subjected to influence by powerful forces and paid lobbyists.

I don’t have time to research this, so I could be wrong, but I think a poll found that the majority of Californians favor raising taxes. However, even raising taxes by a ballot initiative requires a supermajority, not just a majority.

And it’s well over 40%, btw, not just 30%. The schools alone are required to be 40% of spending — that was determined by a ballot initiative. So all other ballot-required spending, such as on prisons, is on top of that required 40% going to schools.

On a previous thread we were given a link to an analysis that was a few years old that said that about 30% of spending was controlled by initiatives. Has there been a new initiative? And do you have a link to the school initiative you mention?

Actually, the latest polls I’ve seen here are that majorities like the 2/3 rule — http://articles.latimes.com/2009/nov/09/local/me-poll9?pg=3

Everyone keeps saying “the problem is we can’t raise taxes.” From what I can see the problem is that spending exceeds revenues. One solution is to raise taxes. Another solution is to lower spending. Even if it’s 40% fixed, what proposals have been put forward to cut spending? And are there any that aren’t on the order of “let’s cut what’s most visible and painful to the voters” instead of “let’s cut administrative payroll” or “let’s privatize services currently run by State employees”. Not that the latter is an automatic panacea, but what honest effort has been put forward to show a strategy for cutting costs? I haven’t seen a link to that here yet. All anyone is talking about is raising taxes. There is an alternative – cut costs and cut services.

Actually, since Schwarzenegger is sending all state employees home without pay 3 days a month, that (I assume) works out to a 15% cost in administrative budgets.

Privatizing government functions doesn’t always lower costs. Look at Medicare Part D (is that the correct name?) The private plans are costing the government 15% more than the plans run by the government.

In general I disagree with the assertion that there is that much “waste” in government. Elected officials have always been saying that they want to cut waste in the government, and there is almost no downside to doing so. Unless you assume that they are incompetent*, cutting “waste” is implausible.

The CA government has tried to cut prison spending, but it is now at the stage where CA is losing lawsuits brought by the feds (under Bush) to provide more healthcare, and more room for prisoners

*given that the CA government does brilliantly at cutting pollution, and reducing energy use per capita, I’m not willing to assume incompetence.

If by “privatizing” you mean “paying private companies to do what used to be done by government workers” then I’m skeptical that you actually can get much savings that way. On the other hand, if you mean “cutting off services entirely and making people buy things on the open market that taxes used to pay for” then, certainly, “privatizing” can cut spending.

Government contractors aren’t really that much more “private” than government workers. They’re paid for by taxes and aren’t subject to the kind of market forces that McDonalds and Burger King face.

@Doug S.

Usually the defense of privatization is that private workers aren’t encumbered by as many expensive regulations as government workers. They don’t have to go through an expensive bidding process for subcontractors, they don’t have unions, etc. However, this obviously ignores the fact that they also have much higher salaries for the top-end and have shareholders to pay, and also those bidding processes exist for a reason.

The problem is that the stats are hard to study since privatization is usually accompanied by a change in the expected deliverables, so it’s often hard to say who’s right.

Yes, those are two solutions — two generally wrongheaded solutions.

Then there’s the rational, moderate solution — which is to minimize pain by raising taxes (but not as much as you’d have to if you were relying on taxes alone), and lower services (but not as much as you’d have to if you were relying on spending cuts alone).

It’s dishonest to talk as if Democrats have been refusing any and all spending cuts. That’s simply not true. Democrats want to do both. The extremists on this issue are Republicans, who — both nationally and in California — will not consider any deficit-reduction bill that includes raising taxes at all.

* * *

Proposition 98, requiring 40% of general California funds to be spent on k-12 + community colleges, was passed in… 1988, I think? It’s not new, anyhow.

My point isn’t to say that the current crisis is caused by prop 98. I think the current crisis is caused by a method of lawmaking that encourages irresponsibility (by letting voters and lawmakers pass expensive policies — such as tax cuts or new prison laws — without simultaneously committing to a method of paying for them.) My point in bringing up prop 98 is only and simply this: Cutting the California budget isn’t nearly as simple as you imagine, Ron.

Furthermore, the appropriate time to talk about how to cut the budget isn’t now. It was back when these expensive measures and tax cuts were passed.

From a defense of prop 98:

I don’t think tax cuts are always bad. I think huge tax cuts (or any expensive program passed without a plausible plan for paying for them), are bad.

According to the PPIC (which claims to be non-partisan, but I don’t know anything about them):

It’s possible, of course, that voters favor both keeping the 2/3rds rule and raising taxes. Voters are often contradictory in that sort of way. Or maybe this reflects a more complex view — “I’d like to raise taxes (among other things) right now to deal with the current crisis, but in the long run I agree that taxes should be hard to raise,” or something.

In no particular order:

With regards to privatizing services currently run by the government, as I said – but as those of you citing me failed to quote – “Not that the latter is an automatic panacea”. It’s an example of what kinds of avenues one can investigate to lower spending.

However, privatizing a government function can save a lot of money even if wages stay the same. From the Wall Street Journal:

Retire at age 50 at 90% of the final year’s pay? That’s insane. I don’t know about privatizing the cops or firemen, that’s a bit extreme even for me. But privatizing prison guards I can see. The point being that privatizing functions may not cut wages but can easily cut benefits, especially ridiculously favorable and costly retirement packages (in comparison to the retirement packages of the people paying the taxes to support them).

Amp:

That’s your opinion. Others would say that California has been making promises it couldn’t count on being able to keep for years. They say that the California legislature has raised the tax burden to excessive levels and driving businesses and taxpayers away. The only rational thing to do is to either keep taxes flat or lower them and to cut services to match, counteracting the extremism that the California legislature has exhibited for a number of years.

You must be talking to someone else. I haven’t mentioned either political party at all. I don’t know about California state politics, but unfortunately when Republicans have been in power nationally they’ve overspent as well.

Which brings me to ask the question once again – what plan has been put forward that would cut spending and services? One, mind you, that is designed to minimize disruption to the public instead of maximizing it in an attempt to put pressure on the public to permit the raising of taxes?

As far as the 40% goes, that’s a percentage. So if the budget is cut overall part of the cut can be taken from the schools. I don’t know what the school funding situation is in California, I’m sure they can always use more money, but if the budget is cut the schools can be included.

True. Those policies also include signing labor contracts that promise absurd pensions and post-retirement healthcare benefits. What other expensive policies have been passed? Obviously you don’t favor tax cuts or the new prison laws. But what expensive policies that you DO favor have been enacted? Maybe California can cut them.

I didn’t say it was simple. I certainly don’t imagine it. I’m saying I haven’t seen the case made that it can’t be done without raising taxes. Will that process take something away from people that they want? Will it take things away from them that they use? Will it cause a degradation in the quality of some people’s lives? No doubt. But so far the main theme here is “this is all caused by not being able to raise taxes”, not “this is caused by trying to spend money we don’t have”.

Now, you’ve said:

And that’s true. I have to say that I think of a government program as some function or service that the government does. I don’t see tax cuts as a program – they affect the finances that fund a program. But yes – passing expensive programs without passing the necessary means to pay for them (whether it’s a tax increase or a cut in expenses elsewhere) is misgovernment. It’s generally caused by politicians’ who are more concerned about being re-elected than they are about doing a proper job of governance. So they make promises to pressure groups, be they unions or corporations or advocacy groups for various causes that can threaten to turn out the vote. Contradictory promises. Expensive promises. Promises by Democrats and Republicans alike.

Now the chickens have come home to roost. The bottom line is that California has to either raise taxes or cut expenses, and “raise taxes” seems to be pretty much both politically and legally impossible. The electorate is telling the politicians “cut spending and don’t raise taxes”. The politicians will have to break promises to do it – promises they never should have made and knew they shouldn’t have made when they did so. By raising expenses knowing they couldn’t raise taxes to match they essentially defrauded the taxpaying public. It’s time for them to come clean and show people just what the alternatives are.

By “they” do you mean the workers or the politicians? Because if you mean the latter then I DO think they are incompetent – or else California wouldn’t be in this mess.

I don’t know anything about the California civil service. Here in Illinois it’s quite safe to say that there’s a huge amount of waste in government. The TV stations and newspapers run series every year showing highway workers who spend much of their time sleeping or eating lunch and administrative workers whose only job description seems to be “stay related to a politician”. The State’s government is rife with people who are unproductive. Numerous State agencies are in facilities that are overdesigned and where the rent or lease was over market value when they were signed but whose landlords are politically connected. Top-heavy management is common. I’m simply guessing that Illinois is not unique, but I could be wrong. I just doubt it.

Interesting discussion.

Have you seen this CA budget simulator? http://www.next10.org/budget/challenge.html#

It demonstrates how difficult it is to balance the budget . . . I can’t discern any political bias – but there may be one that I didn’t see. The simulator has lots of information about each choice you make for your budget (e.g., background on each budget item, and pros/cons of reducing or increasing spending on each issue).

One interesing effect that the simulator points out – if you select any options to raise taxes 40% of those new revenues are automatically dedicated to new school funding ‘cuz of prop 98 (which may be a good thing, but you don’t have an option about it), and only 60% of any new revenues go to other needs or deficit reduction.

It also tells you the percentage of *other* survey takers who chose to increase or decrease funding for each budget item.

I don’t know where that 30% number comes from (perhaps I didn’t read the post or comments carefully enough), but it probably does not include the effects of intitiative mandates like the “three-strikes” law requiring mandatory life sentences for repeat offender felons – which do not require us to put any expenses directly on the state credit card, but still have substantial budget consequences.

The simulator has a political bias in the direction of not believing balanced budgets are possible; selecting all the lowest-spending, highest-taxing options, you still end up $800 million in the hole.

is that a bias or reality? asking the question honestly.

yes, to balance the budget in the simulator you have to choose the most draconian education/human services/environment cut options AND the most agressive tax increase options.

perhaps the simulator is not creative enough in its options . . . or maybe that’s just where CA is after a couple decades of passing initiative after initiative of bond-funded projects – so that the legislature never had to pay the political price of making hard decisions in real time (i.e., pay-as-you go for new spending).

Well, it’s a reality in that California is in a tight situation budgetarily. But they can get above water; it’s a question of will, not material fact.

Are you saying that you know of a solution, then?

Are you saying that you know of a solution, then?

Yes. Spend less money than they bring in. Same solution that’s provided fiscal stability to governments since Hammurabi.

The “but-they-can’ts” list that eager fingers have already typed is a list of political problems, not resource problems.

The bottom line is, state budgets have to balance. States are not issuers of sovereign debt; they can’t create money the way the Feds can. They can borrow, and issue bonds and such, but those instruments all have to be redeemed in cold hard money. This is one reason why state budgetary politics have tended to be more pragmatic than national politics – the national players have the luxury of printing money, and often do.

States have to pay their bills.

If the services must be provided, then revenues must be raised. If taxes must not be raised, then non-tax revenues must be raised. If non-tax revenues cannot be raised sufficiently to balance the books, then services must be cut.

Run this loop, and whichever “must” or “cannot” turns out to be the weakest link will break, and the problem is solved. Alternatively, the government of CA will prove itself collectively cognitively incompetent to solve this Kirkian supercomputer-killing-paradox loop of budgetary reality, and will blow itself up, in which case CA will get a new government, hopefully one more capable.

That would be a destructive and expensive process, however, so hopefully someone will be able to yield on one or more of those “musts”.

My understanding is that California is structurally in the hole somewhere between $10 and $20 billion a year. (If the economy picks up, they’re in much better shape as existing tax levies firm up their actual performance, naturally, so a lot depends on that as well.)

California has 37 million people. That’s an annual shortfall of $270 a head, maybe somewhat more. Not peanuts, but not overwhelmingly unachievable, either.

It’s a question of will, in a way.

I’d look at it in a different (but non-contradictory) way: It’s a question of political incentives. This is oversimplifying, but in general: Within the political incentives created by the California rules, nothing happens unless both parties agree to it. But it’s not the case that both parties will gain a political benefit from reaching an agreement with the other party. In that situation, solutions appear to be politically unlikely if not impossible.

Which means what? Rather than make the budget balance, the legislature will let the state go bankrupt? Because there don’t seem to be a lot of other choices.

One alternative would be for a constitutional amendment to be passed that would change that 2/3 requirement. Would that in fact itself require a 2/3 approval of the electorate? I seem to recall from a previous debate that any amendment that made a substantial difference to the way the state operates needed to pass the legislature and then be approved by a 2/3 (or was it 3/5?) majority of the electorate. What are the odds of that? Besides, it would take another year or two.

Another alternative would be for the State of California to attempt to issue bonds and go into future debt to service present debt. I don’t know what kind of legislative or electoral approval that takes. It’s real bad policy. And God knows I wouldn’t buy those bonds.

I asked this way up thread, but it’s looking like an essential question – what happens when a State goes into bankruptcy? A corporation going into bankruptcy re-organizes. What would be the equivalent for a State? Maybe the entire legislature and executive branch would have to resign and a special election would be held so that the electorate would re-fill all the positions. “Throw the bums out” writ large. Is there any law (State or Federal) to cover this?

Amp, you speak of political incentive. What is the political incentive for the California legislature to avoid bankruptcy?

Marmalade:

It was from a previous thread where this was touched on. A link was given to a study that found that in 2003, 30% of California State expenditures were fixed by law based on citizen initiatives. We’re guessing that there hasn’t been much since 2003 that’s affected that number. I believe that the “three-strikes” law was included. But even if it wasn’t, figure that most people who have managed to commit 3 felonies in their life are already going to spend the rest of their life in jail, or at least most of it. I’m going to make a wild guess and speculate that the law was passed in the wake of some horrific crime that someone with 3 felonies committed, but that the number of people actually affected – people with 3 felony convictions who would otherwise end up finishing their sentences while they were still alive – is pretty small.

Schwarzenegger expressly structured this so that no spending cuts would balance his tax cut. This is a textbook example of Republican/conservative fecklessness and irresponsibility

Schwarzenegger is certainly a Republican. However, I would not call him a conservative.

in some counties particularly inland, property taxes have taken a hit and sales taxes revenue which provides most local services. The state’s been taking money from cities and counties to balance its own budget causing more shortages locally.

Not to mention the housing market including new housing market bust in so many areas.

But hey, you hire an actor through the public vote to run your state, that’s what you get.

In the present California budgetary crisis, it seems to me that the Democrats are saying “We need to balance the budget by raising taxes and we refuse to cut services.” The Republicans are saying “We need to balance the budget by cutting services, and we refuse to raise taxes.” Neither party will go along with Amp’s suggestion of doing some of both. I can’t see how that supports the proposition that it is solely the Republicans that are intransigent and bear responsibility for this situation.

Yes, the issue of expenditures fixed by citizen initiative is a problem. But in going through those links it seems there are some large expenditures that will get worse in the future based on union contracts promising large pension and healthcare benefits – something that Illinois has done as well. Is that purely an executive function? Or is the legislature, that has been dominated by Democrats for some time, responsible for the final approval of them? How much of the state budget is tied up in that? How worse is it going to get when you have to pay those pensions out as well as hire people to actually do the jobs that the future retirees now hold?

Unions get these large contracts in large part because the politicians want their support in elections – a consequence of a) permitting public employees to form unions and b) government getting so large that public employees form a significant part of the electorate. When a large number of voters have an interest in increasing government spending because they either work for it or are supported by it you have a recipe for financial disaster. “He who proposes to rob Peter to pay Paul can always count on the support of Paul.”

Radfem:

Can’t argue with that. Of course, as we have seen in the John Edwards case and many others, many politicians are much better actors than anyone who works in Hollywood. They’ve just found the ultimate reality show to appear in.

Amp @ 29 – I agree, that is a different but compatible way of looking at it.

I think all legislators should be trained in playing “Republic of Rome”, a brilliant boardgame simulation of the political system in republican Rome where players control a Senatorial faction. The point of the game is to win by amassing the most political power – but everyone can lose the game, no matter what their personal standing, if they let the republic’s condition deteriorate. (Because the state collapses, and the players are ripped to pieces by the mob or the barbarians.)

It’s an intriguing exercise in screwing your neighbor, but not so much that you can’t work together to stop the barbarian horde that wants to kill both of you.

But even if it wasn’t, figure that most people who have managed to commit 3 felonies in their life are already going to spend the rest of their life in jail, or at least most of it.

I think you’re really overestimating how serious a crime a felony is. If you steal something that costs more than $500, that’s a felony in most states. Drug crimes become a felony is you have more than some very small amount of the drug in your possession. Often, they are the exact same crimes as misdemeanors, just with a higher dollar value.

I’m pretty sure most people with three theft over $500 convictions aren’t spending the rest of their lives in prison in most places.

This analysis from the Legislative Analyst’s Office (like the Congressional Budget Office?) is really interesting, though it’s also kind of old (2005). (Sorry, I’ve got like five other things I should be doing.)

So, the way the law works, the first offense needs to be “serious or violent,” but the subsequent offenses can be any type of felony, and there is enhanced sentencing even on the second offense. So there’s impact on prison population even before you get to three strikes. There’s also a certain amount of prosecutorial discretion, so in some counties, they’re using the three-strikes on everybody who could qualify, and in others, they’re only using it for violent crimes or for crimes the community is particularly concerned about. The law also requires that sentencing for multiple felonies committed at the same time (like, let’s say, an armed robbery and an aggravated assault – that’s two), must be consecutive, not concurrent. The report mentions that three strikes has led to a much older prison population than the state had before the law, which increases health care costs – and the state is under all sorts of court orders to improve its health care for inmates.

This is a NYT’s editorial related to an ongoing prison reform lawsuit. This is from last year. It mentions that California paroles a much higher percentage of its inmates than any other state. Most do around 40 percent. California does around 70 percent. And since a lot of people find it hard to comply with parole conditions, they end up back in prison at a very high rate in California for things like failing a drug test.

There’s a lot of compounding factors going on, with these policies driving up prison population, while the courts mandate the state do more (and spend more) to protect the basic civil rights of inmates.

Forget any constitutional convention this year.

http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-constitutional-convention-2010feb13,0,2734408.story

RonF said:

Yes the study finds that 32% of CA’s budget is constrained by voter-passed initiatives (not including the 40% required school allocation), and it does include the effects of the three strikes law in the analysis.

However, it’s also from a researcher from the Initiative & Referendum Institute, which claims to be a “Non-profit non-partisan research and educational organization dedicated to the expansion of the initiative and referendum process in the US.” The abstract of the study claims:

So while I haven’t refuted the findings of the study AND I haven’t produced contrary findings (not from lack of looking), the author’s potential bias makes it a bit questionable.

So why does it matter? I’m just supporting kathy a’s position above (which I agree with):

which RonF countered with:

The initiative process in CA was a terrific experiment, but we found out that voters will just vote themselves one giant bond-measure after another, and relieve the legislature of having to make hard political choices (i.e., raise taxes or cut services). The initiative system also invites huge amounts of distorting special interest funding, which can – and does – come from outside the state.

Wait, wait, wait … the 32% doesn’t include the 40% school funding?

So we’re looking at 72%, total? Is that right?

—Myca

I think it did include the 40 percent for schools. That’s 40 percent of the general fund, which is just one part of the total budget, so you could still get 32 percent. However, I don’t think you’d want to just assume that 32 percent continues year over year, particularly because the prison spending increases exponentially and cumulatively as more and more people go to prison for life.

Ok, so I read the cited study (at http://tiny.cc/1gGl7), and yes, it did include the effects of prop 98.

However, it found that only 30% of the state general fund was constrained by prop 98 in 2003/2004 – because local municipalities contributed the rest of the funds. And, the study found that only 2% of the budget was constrained by other initiatives – it does seem that prop 98 is the biggie.

But to bring things up-to-date . . . the CA Legislative Affairs Office (which, of course is ‘sposed to be pretty objective) reported that for 2009 prop 98 constrained over 40% of the general fund (http://tiny.cc/Jd1oi). The change between 2003 and 2009 is due to the *really* complex mechanics of prop 98 (what a nightmare). And due to the fact that when the state reduced car registration fees, the state general fund took on more of the prop 98 burden so that the localities would not suffer from the registration fee revenue fall-off.

So, it seems that spending more than 40% of your state budget on k-12 education and community colleges really is a constraint on budget flexibility BUT CA schools are quite terrible. It seems that we have these options:

a) repeal/override prop 98 and spend less than 40% of our general fund budget on schools, and/or

b) raise the car registration fee again to and take more money from local municipalities to meet prop 98’s requirement, and/or

c) close schools and/or community colleges, and/or

d) continue to see a decline in school quality.

I’d put these options in RonF’s “live within your means” paradigm.

We could raise revenues to try to save school quality while meeting other budget needs. But of course, new revenues raised would be constrained by prop 98 – so that 40% (or so) would go to education while 60% could go toward other problems.

I don’t really have a problem with that . . . but the idea that the initiative process in CA has not contributed to our current mess seems disingenuous.

It also seems that this bugeting system is soooo complicated, that it’s really hard to understand it well enought to make intellegent decisions about it. I’m not saying that voters are unintellegent, but just that most people do not have the time/inclination to study the consequences of their votes in the nauseating detail required.

As a California resident, I just want to drop a note in to say that “cutting spending” does not happen in a vaccuum. If you cut, say, services to the mentally ill, you not only ensure that those previously served will start to back up into the public hospital emergency rooms and criminal justice system (both of which are funded by tax dollars) but also that the service providers will be laid off, increasing unemployement which costs the state’s unemployment fund and drags the economy down as the laid-off workers are forced to cut their own spending.

As far as I can tell, a state “goes bankrupt” by simply declaring that it won’t pay its creditors, and then not paying its creditors. This has the consequences of people that California promised to pay not getting their money (among them would be bondholders and former state workers receiving pensions) and that, in the future, people will refuse to extend credit to California.

great comments from marmalade and elusis.

this set of problems is not going to be easily solved, in part because nobody is in charge of the whole package — and lots of pieces thrown hastily into place over decades now cannot easily be changed. it is really quite discouraging, particularly with many of the political players [i’m looking at you, state legislature] being more interested in posturing for the next election or whatever than in doing the hard work of making our state work.

the budget problems in CA have been growing for years, and are not helped at all by the general economic decline. but it has really gotten past a critical point.

Here’s a perfect illustration of why it isn’t so simple to “just cut spending.” Laying off 850 rehabilitation workers teaching GED and job skills to inmates and leading anger management and substance abuse groups not only adds 850 people to the state’s higher-than-average unemployment, but ensures that our breathtaking 70% recidivism rate (the highest in the nation) will go even higher.

(And in the meantime, our crazy policy of letting the governor systematically overrule nearly all parole board decisions keeps people who have taken responsibility for their crimes and been rehabilitated in prison for decades. From the Sentencing Project (pdf) – “The highest proportion of life sentences relative to the prison population is in California, where 20% of the prison population is serving a life sentence, up from 18.1% in 2003. ” Even though the California Supreme Court has said that the state has to show “some evidence of risk” to support overturning a parole board’s decision, little has changed. So our prisons are choked with inmates… to whom we are providing fewer and fewer services to make sure that if they do get out, they don’t come back.)

RonF,

Just read that three-strikes was sponsored by the correctional officer’s union. Let’s see … tough on crime vs. unionized government workers … does that change your view at all?

You know, when it gets right down to it the only way to fix this may well be bankruptcy. If it works like personal or corporate bankruptcy then all contracts and outstanding bills get voided out. The board of directors and the corporate officers are replaced (which in this case I’d guess would be the Legislative and Executive branches). You start from scratch, and you have to come up with a balanced budget or else one is imposed on you.

It’s hardly a perfect solution. Someone’s going to get screwed. But under the present course lots of someones are getting screwed now and will continue to get screwed in the future, so all bankruptcy changes is who gets screwed, not whether or not someone does. I wonder who would serve as the Bankruptcy Court? Probably the U.S. Supreme Court, based on Article III, Section 2, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution:

Which leaves the question of who brings the case? I should think someone that the State owes money to but hasn’t paid. That would be interesting. Let me take a local example. The State of Illinois is way behind in Medicaid payments to pharmacies, especially the smaller non-corporate ones. Could some mom-and-pop pharmacy force the State of Illinois into bankruptcy court? God knows that Illinois owes more than it can pay – the obligation in pensions to government workers alone is far more than it can pay.

Good Lord – now that I think about it there’s plenty of states where this situation exists. California, Illinois, New York, etc., etc. Plenty of states have borrowed more than they have any realistic hope of paying back. I’m no expert in this. Does anyone know what conditions have to exist in order for a debtor to be forced against their will into bankruptcy?