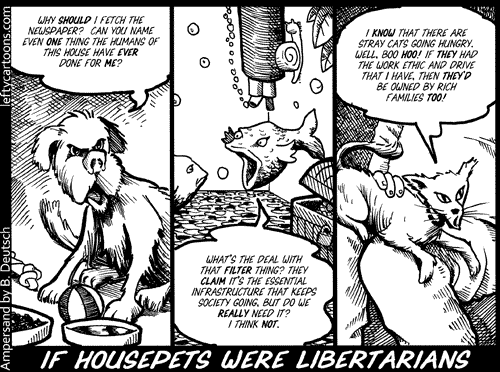

That’s an old cartoon, but I like it, and so I’ll take any excuse to post it. Such as this email I received from “Mark”:

Just caught your “If Housepets were Libertarians” cartoon

Boy are you confused about what Libertarians are. It’s not about selfishness, it’s about not being FORCED into charity. What’s more damaging however is the impression you form in the minds of those who take your little drawing at face value. Read a book would you; how about “Atlas Shrugged” or “Wealth and Poverty” or “ Freedom to Choose”. If you are going to dabble in political thought don’t let yourself be pigeonholed as a complete neophyte.

I’m really tickled by the idea that if you haven’t read a book by obscure 1970s anti-feminist George Gilder, then you’re a complete neophyte.

I don’t interpret “If Libertarians Were Housepets” as saying that libertarians are selfish (that’s more the theme of this cartoon). Rather, it’s saying that Libertarians have dangerously little understanding of how society actually works. As Mark Thoma writes:

Where I part with many libertarians – perhaps due to my background – is in the idea that government is almost always at odds with liberty. In my case, government played a key role in providing me with opportunity – education is one example, without tuition of $100 per semester at a state school, I probably would not have gone to college – but the opportunities government provided me go beyond education (and also see the examples given in the article for women and minorities).

Bruce Bartlett argues: ((I’ve cut out a sentence in which Bartlett says that blacks no longer have less freedom than whites, generally. One look at who goes to prison in the US is enough to refute that claim.))

Many government interventions expand freedom. A good example would be the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It was opposed by libertarians like Barry Goldwater as an unconstitutional infringement on states’ rights. Yet it was obvious that African Americans were suffering tremendously at the hands of state and local governments. If the federal government didn’t step in to redress these crimes, who else would? […]

One could also argue that the women’s movement led to a tremendous increase in freedom. Libertarians may concede the point, but conservatives almost universally view the women’s movement with deep hostility. They think women are freest when fulfilling their roles as wife and mother. Anything that conflicts with those responsibilities is bad as far as most conservatives are concerned.

But although Libertarians may concede the point, Bartlett points out, in the end they still vote Republican, because they’re entirely focused on economics, and on government as the enemy of liberty. This is problematic because libertarians tend to have an extremely narrow conception of what liberty is: not paying taxes.

The Cato Institute publishes an annual survey of economic freedom throughout the world, but produces no surveys of what countries have the most political or social freedom or those that have the most libertarian foreign policy.

Furthermore, economic freedom tends to be determined primarily by those measures for which quantifiable data are available. Since it is very easy to look up the top marginal income tax rate or taxes as a share of GDP, these measures tend to have overwhelming influence on the ratings. As a result, countries like Denmark, which are very free every way except in terms of taxes, end up being penalized. Conversely, authoritarian states like Singapore don’t suffer for it because they have low taxes.

Although not all libertarians are well-off white men, nearly every libertarian I’ve met had at least two of those three traits. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. I think that if you’re economically comfortable, white, and male, it’s much easier to imagine that government is the biggest threat to liberty in the world, and to minimize or dismiss how other factors — such as racism, sexism, and the concentration of wealth and poverty — also constrain liberty. For George Gilder — a white man with more money than he could ever spend — perhaps the biggest threat to his freedom is taxation. But most of us aren’t George Gilder.

I think you and Bartlett are slightly unfair, or at least limited, in your view of libertarian political philosophy. (Although admittedly if you went solely by people like “Mark,” you would be forgiven for this. If you’re interested in the intellectual roots of libertarianism, I’d recommend Mill’s “On Liberty” and Nozick’s “Anarchy, State and Utopia” — the latter has been pretty thoroughly picked apart by Rawls and his followers, but is still thoughtful and well-written.)

The libertarian conception of economic liberty goes well beyond taxes. It also considers matters like

– government seizure of private property with government-decided level of compensation (as in Kelo, where the town of New London forcibly took homes that the owners didn’t want to sell, in order to create an industrial complex for Pfizer);

– government regulation of what one can do with private property, including rendering it essentially worthless through environmental regulations;

– government mandates on who can do what kind of work (as in requirements that any hair salon have trained cosmetologists, even if the salon is catering solely to traditional African braiding, which is not even taught in the average cosmetology school because they’re so white-culture-focused);

– government mandates on the number of hours, type of conditions and wages for which one may work;

etc. etc.

If the Cato Institute is measuring only economic freedom, why does it matter whether Singapore is authoritarian with regard to speech freedom, or Denmark is tolerant with regard to religious or sexual freedoms? One might critique the Cato index for laziness in relying too heavily on tax rates without consider issues like those I listed above (government seizure and regulation of property; regulations on business and employment). But it’s nonsensical to say that Singapore can’t be relatively economically free if it is somewhat socially and politically authoritarian.

I was a libertarian during high school, and while I no longer agree with the overall philosophy, I think you can be more just to it than you were in this post.

Hey, Amp, you need to practice your cat heads. Unless that person has a pet rat.

I myself see some value in some of what I’ve seen described as “libertarian” philosophies, but I’ve not studied it in depth or in any original sources. I’d say that I personally see taxes as a necessary evil – while society’s ability to take money from me by force is bad, the bad is outweighed by the good that is done with it. Or, at least, should be. The public good provided by things like actual infrastructure (roads, bridges, airports, police and fire stations) and certain essential services (police, fire departments).

But what I see is that there are many people who make the presumption that if 50% + 1 of the electorate (or even just 50% + 1 of a legislative or judicial body) believe that something is good (e.g., numerous social services) then that automatically justifies taxing people to fund it, or (as we saw in Kelo and thanks for reminding me, PG) using other means of taking private property and putting it to that use. The idea that government itself is a necessary evil that needs to be closely constrained against abusing individuals seems to be losing ground rapidly.

To my mind – and I don’t claim to be libertarian or to speak for those who are – the greatest threat to liberty is creating a class of people who are dependent on the government for their life’s needs. The larger the class of people are who depend on the government (in all it’s myriad layers) for things like housing, employment, health care, etc., the less liberty they have and the less we all have.

Like the last quote. Source?

Put aside the hot-button issues: Western governments tend to be the main engines combating or mitigating disease, natural disasters and simple ignorance. I have a standing offer for my libertarian colleagues: I’m willing to concede that government caused the Holocaust (death toll 20+ million) if they’re willing to concede that government stopped smallpox (death toll 300-500 million). This is perhaps the paradigmatic case of privilege: People complaining that government is the greatest threat they face – and the complaint may well have merit, because government has eliminated all the larger threats.

(Oh, and having spent multiple posts picking at one of Amp’s cartoons, let me seize the opportunity to say that I find this one — and the Libertarians in Heaven one — nail the topic cold. The expressions of indignation are perfect.)

I think that if you look at your statement that you’ll realize that this is far too simplistic to apply to real life. I won’t insult your intelligence by naming a threat to liberty that is obviously greater than the class you mention.

But those are the people who most visibly represent libertarian political philosophy in the US. It’s like those conservatives (or Republicans) who claim that Bush the Younger was not a real conservative (or Republican). You may think that but it’s no longer reflected by reality. The “Mark’s” of the world are what libertarian political philosophy has become in the US. You need look no further than the Libertarian Party to confirm this.

While I would agree with you that they offer an extremely simplistic, immature and stunted libertarianism, that doesn’t refute the fact that that is what libertarianism has become. I believe that is what Amp’s cartoon is addressing.

a side note on rhetorical structure: the email from “Mark” is a textbook example of ‘concern troll’.

And he’s no true Scotsman either!

I have strong libertarian leanings, some ways. However, among other things (I like govt. protecting rights ), I really think that the “state’s rights” thing is waaay overdone. Like abortion should be decided by the state? What?

The government should protect us (law and order to prevent people from hurting one another, and bodily integrity rights, general freedom protection) and offer us opportunity to pursue our happiness (education, roads, etc).

The government should not try to make things cheaper for consumers unless individual rights are being violated (corn subsidies, oil wars).

Women’s bodily integrity is more important to me than not subsidizing corn, thus I vote democrat.

I don’t think “Mark” is as comparable a representative of libertarianism as the president that the Republicans actually nominated and elected, twice, is a representative of the Republican Party. If I just went by, say, Playboy, I could say that liberalism is represented by misogynists and homophobes. I don’t think it’s altogether intellectually honest to judge a philosophy by its least appealing purported adherents — it’s verging on straw-man argumentation (not quite strawman, since Mark exists, but his understanding of libertarianism appears to be at a literally sophomoric level such that I don’t feel badly about humming “If I Only Had a Brain”).

Saw this quote from Maimonides the other day:

And the first thing I thought was “No true Scotsman … ”

It made me wonder about the earliest recorded use of the no true Scotsman fallacy.

Do you have to be a libertarian to worry about government use of power and to think the government is not always a benign force? I don’t consider myself libertarian in the least, but I have a huge problem with Kelo because I don’t consider a private business venture to be a public good for the purposes of seizing property, no matter how many jobs it creates. Conversely, the libertarian might oppose environmental regulation, and point to the jobs created in polluting industries as evidence of the benefit of this type of economic freedom. But if I get sick from their pollution, my freedom has been impinged upon by a private business venture, just as that of the property owners in Kelo. There is significant overlap in my views on drug laws and those of libertarians, but does that mean I am taking a libertarian position or could my position be perfectly consistent with my own medium-lefty world view?

It might not be fair to judge libertarians based solely on Mark, but Mark is pretty typical of most libertarians I have encountered.

And your Playboy example is exactly the type of thing that makes me uncomfortable calling myself a liberal, though “progressive” has always felt a little pretentious to me.

my dog’s a libertarian and like to licks his balls , maintaining its his first amendment right like nude dancing. me and my conservative buddies say its obscene and violates community standards. my gf andrea says its misogynistic hate speech when done around her so she hooked up with my fascist cousin and cut his balls off.

Sorry, that was also from Bartlett’s article. I’ll have another post quoting more from Bartlett in a couple of days.

* * *

BTW, everyone, I did email “Mark” to let him know I posted this. So keep in mind that he may be reading your comments.

http://www.theagitator.com

He’s clearly a libertarian. He says he’s a libertarian, He worked for Cato, and is now working for Reason magazine.

He opposed the Iraq war, spends a large amount of his time writing about police actions that hurt people as part of the drug war, and supports a number of policies that most alas readers would agree with.

There’s no shortage of narrowly focused morons offering comments on the internet. Libertarians have plenty. But if we’re discussing logical flaws, assuming that the options are “Oppose the small Pox vaccine” or “admit that expanding government power is a good thing” is a clear false choice.

PG siad:

I think Amp is lampooning the libertarians one generally meets rather than the philosophical libertarians that actually do more than read a little Ayn Rand.

I say this because every self-proclaimed “practicing libertarian” that I’ve had the misfortune of meeting is more in line with the “Mark”s of the world than with the alternative.

Every person that I’ve met that engaged libertarianism with some form of intellectual approach seems to end up more like yourself, PG (i.e. an ex-libertarian). Usually because they realize that it is disconnected from reality and once they get some real world experience they (as you put it) “no longer agree with the overall philosophy”.

Perhaps the examples I’ve encountered are, in fact, anecdotal. But, in my experience, evidence of Amp’s personification of the “average libertarian” is overwhelming to the point of leading me to believe that your “philosophical libertarian” is, at worst, non-existent or, at best, so much a minority that s/he does not influence libertarianism-in-practice in any meaningful way.

Joe, I agree that Radley Balko is great, and he’s definitely a libertarian. I read his blog often, and I link to it pretty regularly (most recently, earlier today).

But I don’t think he’s typical, unfortunately.

Okay, then. Forget about “Mark.” What about the Libertarian Party? That’s a pretty good example of the simplified version of libertarianism. Sure, they have a platform that expounds on a bit more but, when they run for office and when they get media attention, they proclaim the same poorly thought out positions.

Libertarianism has value in that there should be no unaskable questions about the appropriate role and scope of government. That doesn’t mean the answers will always make Ayn Rand happy, of course, but it helps get us that much closer to the ideal utopia each human should be living under if we consider the merits of and problems with every approach. The Kelo case provides an excellent reason to examine Government economic power, but that examination icludes considering who benefits from it as well as whom it impacts negatively. In that specific case, I think New London was in the wrong, but in a different instance I may think differently.

PG:

I think the point is that economic liberty isn’t the only or even always the most important freedom. Indeed, I would argue that without social and political freedom, economic freedom is, if not meaningless, greatly restricted.

chingona,

Do you have to be a libertarian to worry about government use of power and to think the government is not always a benign force?

No, but it helps, since libertarians are consistently suspicious of the government instead of being suspicious only when the government seems likely to tread on the particular rights one cares about personally.

I don’t consider myself libertarian in the least, but I have a huge problem with Kelo because I don’t consider a private business venture to be a public good for the purposes of seizing property, no matter how many jobs it creates.

OK, but then you’re prioritizing individual property rights over what has been determined by democratic means to be in the interests of the community. If the people of New London did not consider the new complex to be in the community’s interests, they could have voted out the city council members who thought that it was and stopped all the plans.

Conversely, the libertarian might oppose environmental regulation, and point to the jobs created in polluting industries as evidence of the benefit of this type of economic freedom. But if I get sick from their pollution, my freedom has been impinged upon by a private business venture, just as that of the property owners in Kelo.

Sure, but you aren’t wholly without redress in a libertarian worldview. For example, libertarians do want to retain the courts and the common law right to bring a suit in tort. If you have been harmed by pollution, you can bring a lawsuit about it. If these lawsuits become sufficiently onerous, such that the cost of defending them, paying settlements and awards and so forth is higher than the benefit of being able to pollute, then the industries will pollute less.

MisterMephisto,

your “philosophical libertarian” is, at worst, non-existent or, at best, so much a minority that s/he does not influence libertarianism-in-practice in any meaningful way.

The very Bartlett article that Amp linked and twice quoted refers to this type of libertarian:

A blogging acquaintance of mine who currently is clerking for Chief Justice Roberts fits this description almost perfectly — we even met initially at a Washington-area social gathering while he was interning at the Institute for Justice, albeit a games night rather than a dinner party. (Scrabble is the quiche of the post-undergrad class.)

I know people who fall on a wide range of the political philosophy spectrum, ranging from Communists (albeit of the type who went to business school, learned marketing and work for Greenpeace in the Netherlands) to free-market libertarians, from Southern Baptist Bush Admin political appointees to leftist pagan anarchists. They’re all smart people. I don’t think any of their beliefs are so obviously irrational as to deserve being dismissed out of hand.

Jake Squid,

Could you point me to the specific Libertarian Party national platform you have in mind?

– government regulation of what one can do with private property, including rendering it essentially worthless through environmental regulations;

This is something that really needs some work. I think that the government has a legitimate role in regulating the amount of damage your actions do to the environment that everyone lives with. If you are refining gold, you should not have the right to dump mercury or cyanide into the local aquifer. It’s possible for you to do damage that you cannot pay for.

But what is not legitimate is to use environmental regulation to force particular kinds of land or property use that is deemed desirable but not obtainable through other means. Nor is it legitimate when the environmental effect (one way or the other) is in fact unknown.

I think the point is that economic liberty isn’t the only or even always the most important freedom. Indeed, I would argue that without social and political freedom, economic freedom is, if not meaningless, greatly restricted.

I agree that economic freedom isn’t the most important kind — that’s one reason I’m not a Republican. However, it makes no sense to criticize an annual survey of economic freedom throughout the world for failing to include social and political freedom. Bartlett says, “As a result, countries like Denmark, which are very free every way except in terms of taxes, end up being penalized. Conversely, authoritarian states like Singapore don’t suffer for it because they have low taxes.” It’s perfectly sensible for Denmark to show poorly on a survey of economic freedom if it’s not economically free! Look at the bloody label on the tin!

If the people of New London did not consider the new complex to be in the community’s interests, they could have voted out the city council members who thought that it was and stopped all the plans.

First, was there an intervening election that could have stopped this?

OK, but then you’re prioritizing individual property rights over what has been determined by democratic means to be in the interests of the community.

Good. I thought it was pretty well established that the intent of the Constitution was that governmental powers are to be limited, and that there are individual rights, including property rights, that are to be supreme over the powers of the State. IIRC a lot of pro-gay marriage people have made that argument.

Sure, but you aren’t wholly without redress in a libertarian worldview. For example, libertarians do want to retain the courts and the common law right to bring a suit in tort. If you have been harmed by pollution, you can bring a lawsuit about it. If these lawsuits become sufficiently onerous, such that the cost of defending them, paying settlements and awards and so forth is higher than the benefit of being able to pollute, then the industries will pollute less.

Technically, yes. Practically, no. Even if the polluting organization is in fact an industry with deep pockets (not always true), it’s entirely possible for a small amount of pollution to cause a large number of things like cancer cases, etc., that there is just no way to compensate people for.

PG, do you think CATO’s decision to do an annual survey of economic “liberty,” but not one of social liberty or political liberty, is a coincidence; or does it in some way reflect CATO’s priorities?

By the way, correct me if I’m wrong, but my impression is that CATO’s measure of economic liberty is blighted and narrow. By their measures (as I understand it — too busy drawing to look into it in detail today), someone forced into homelessness and despair by endless medical bills in the US would count as having more economic liberty than someone guaranteed medical care, but paying higher taxes, in Denmark. That’s not, in my view, a very substantive definition of “economic liberty.”

Sure, theoretically, but the argument being made here (and I think it’s a good one) is that although the libertarian label says “We care about all government infringement on rights,” when you open the jar, too often you find an asterisk on the inside reading something like, “*as long as you mean taxes, and we’re perfectly okay with the invasion of Iraq, and by the by, the government should not have done anything about segregation.”

Certainly, but I don’t think that that’s the point. The point was that Libertarians only seem to give (much of) a shit about an extremely narrow definition of freedom, and the Cato Institute’s survey of economic freedom is a pretty good example of this.

Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe they also publish a ‘survey of economic mobility,’ a ‘survey of human rights,’ a ‘survey of racial equality’, and a ‘survey of journalistic freedom.” I doubt it, but maybe.

The complaint, then, is that they take one kind of freedom, define it as the only kind of freedom worth paying attention to, embrace it whole-heartedly, and define themselves as pro-freedom. That’s like calling yourself ‘pro-nutrition’ because you like cheese.

—Myca

PG,

The national LP platform can be found here:

http://www.lp.org/platform

That expounds a bit more on libertarian principles than your average LP candidate will usually do. And a lot more than the libertarians that I and others on this thread have been acquainted with.

PG, I was going to respond, but … wait for it … I agree with everything RonF wrote @ 22.

That’s like calling yourself ‘pro-nutrition’ because you like cheese.

Now that’s a platform I could get behind.

First, was there an intervening election that could have stopped this?

Yes. There’s a New London city council election every two years, on odd-numbered years. The city council approved the development plan in January 2000; condemnation proceedings were initiated in November 2000; in December 2000, the Kelo plaintiffs brought their action in the New London Superior Court. The plan could have been stopped by kicking out the city council that had approved the development the in 2001 or 2003 elections, prior to the 2004 state Supreme Court or 2005 U.S. Supreme Court decisions. Heck, I bet there’s a way to collect signatures on a petition to call an early election. The political party One New London formed to stop the development, but doesn’t seem to have organized until 2005. It won two seats on the city council in the 2005 election — not enough to control.

PG, do you think CATO’s decision to do an annual survey of economic “liberty,” but not one of social liberty or political liberty, is a coincidence; or does it in some way reflect CATO’s priorities?

From what I understand, CATO started doing the survey after it published a 1997 study (also presented to the Senate) about the relationship betwen economic freedom and economic growth. That study specifically disclaimed any presumption that its focus on economic liberty meant that the authors believed other human liberties unimportant:

By their measures (as I understand it — too busy drawing to look into it in detail today), someone forced into homelessness and despair by endless medical bills in the US would count as having more economic liberty than someone guaranteed medical care, but paying higher taxes, in Denmark.

“Right to have medical care provided free of charge” is not included in the quoted list, because all of those listed rights are negative rights, not positive rights. Most “freedoms” are generally framed as negative rights. If I have a right of free speech, it’s a right to flap my mouth free from government censorship, not a right to have people sit and listen to me, or for the government to pay for my speeches to be printed and distributed.

“Right to provide medical care” and “right to receive medical care” would be freedoms from government intrusion thereon (and the state laws that forbid unlicensed practice of law and medicine obtrude on such freedom in order to keep quacks and shysters from screwing people over — or in order to protect the legal and medical guilds from competition, if you’re cynical). “Right to demand medical care without cost to myself” is not what traditionally has been framed as a freedom. It might be an important substantive right in order to be a functioning member of a polity (as I consider education to be), but the freedom to obtain an abortion is not generally construed in American political discourse as the right to have taxpayers pay for my abortion.

Or to put all this a lot more briefly, what you consider to be “freedoms” are what I’d consider substantive rights. Rather than asking only that the government leave me alone to give and receive medical assistance, I am asking that the government provide me with a positive entitlement to the medical assistance.

and we’re perfectly okay with the invasion of Iraq, and by the by, the government should not have done anything about segregation

Lots of libertarians were not perfectly OK with the invasion of Iraq, as you would see if you, say, looked at the Libertarian Party platform of 2004, or statements of the Libertarian presidential candidate (for whom my cousin, theretofore a Republican, voted in his disgust at Bush for the Iraq war; in the last election he voted for Obama).

Libertarians are completely supportive of the government’s ending segregation within its own facilities, workplaces, etc. If a state government wanted to end segregation in its schools, great. Truman’s desegregating the military, also great. The objection is to (a) having governments impose rules on private sector businesses and associations; and (b) having the federal government go beyond what Libertarians consider the Constitutional bounds on federal power in order to tell the states what to do.

And libertarians can get pretty creative about how it would be OK for a government to interfere with the private sector. For example, I’ve heard it suggested that since a corporation is a legal fiction existing solely at the pleasure of the state of incorporation, it would be fine for a state to condition its recognition of incorporation on the corporation’s following the state’s rules on non-discrimination. This could even be extended to limited-liability partnerships or any other entity that requires state recognition. In other words, if you run a store and would like to enjoy the legal benefit of not being personally liable if someone slips and breaks his leg in your store, then in exchange for that legal benefit, the state could require that you comply with non-discrimination rules.

One more thing about the citizens of New London voting out the council if they don’t like taking little old ladies’ houses for economic development …

I cover and write about local government for a living. The reason I do what I do is because I think it’s important for people to know what their government is up to so they can make informed decisions as part of the democratic process.

But it’s a very imperfect system. A lot of times there aren’t complete slates of opponents in local elections. A lot of times the people who run for office are, well, not the brightest bulbs, and people vote for the devil they know instead of the village idiot they also know. A lot of times turnout in local elections is so low that the partisans of the incumbents, who are more organized and better financed by local business interests, easily carry the day. People do not inform themselves. I get calls all the time from regular readers of the newspaper who are upset the government is spending money on X – and think they are tipping me off to some secret plan – when the project was part of a voter-approved bond package I’ve written about 15 times, including all the arguments against it before it was voted on.

Perhaps more significantly in the case of Kelo, things are not easily undone. Once contracts and agreements are signed, they are just as binding as any private sector contract. A town attorney would warn the new, inexperienced board they would face a lawsuit and likely lose if they tried to back out of the deal. Time and again, I’ve seen elected officials take “principled stands” for what their constituents wanted, only to fold in the face of a lawsuit (and usually end up paying attorney’s fees to the wronged party, too).

All of which is to say that, yes, I think certain rights are more important and deserve more protection than whatever your city council comes up with next.

My objection is you seem to be casting any concern for rights as the purview of libertarians. I think there are a number of ways to arrive at the same conclusions and a number of ways to prioritize competing values that still recognize the importance of limiting government power.

(The American government class I took in college used a four-square thing depending on how you value equality, liberty and security. If you value liberty over equality and security, you’re a libertarian. If you’re a progressive, you value equality over liberty but liberty over security, etc.)

chingona,

If you agree with Ron that there are property rights that are more important than the collective interest of the community, is there any level of taxation that you would consider to be infringing on property rights? Or any level of environmental or other regulation, in terms of rendering property unsuable?

And yet we didn’t have substantive environmental regulations in this country until the 1970s, and there have been many celebrated class action suits — often made into movies with Julia Roberts or John Travolta — that dealt with pollution’s causing lots of harm that was deemed to be somehow compensable.

If you study tort law, you learn that while there’s “no way to compensate” for the loss of a limb, or a loved one, at some point you have to come up with a dollar figure to approximate it. How do you think poor Kenneth Feinberg, who administered the 9/11 victims fund, was supposed to manage? (And now he’s going to have to oversee executive compensation for the bailout companies.) If you study modern regulatory law, you learn about cost-benefit analysis and how to put a dollar figure on human life in order to determine whether to mandate a particular safety requirement. We’ve known for years that we’d all be safer if every car came with side-impact air bags that came with a weight sensor in the seats (so that a less-than-average-adult sized person doesn’t get her neck broken by the airbag), but they won’t be mandatory until 2013, because when the technology first came out, it was considered too expensive to mandate. It’s now come down in price enough that the lives saved would be worth it.

Jake,

And which of those principles do you find so self-evidently and inarguably ludicrous that libertarians should be dismissed out of hand?

Perhaps more significantly in the case of Kelo, things are not easily undone. Once contracts and agreements are signed, they are just as binding as any private sector contract.

Since the development hasn’t actually occurred in New London and the whole business seems to have been some expensive foolishness on the part of the city, I don’t think there could have been any terribly binding contracts in play here.

Regarding property ownership, I didn’t think much of O’Connor’s and Thomas’s “boohoo the most vulnerable in society will be the targets of these development programs and will have to accept the government’s cash for their property.” First, if you own property you’re not the worst off person in society. Many people are worse off than you are. Second, if the problem is that the government compensates insufficiently, then we ought to change that, not scrap the government’s takings power — that’s throwing out the baby with the bathwater.

PG,

I wrote:

I’m not sure why you think my complaint is with the LP platform. My complaint is with their candidates and their public statements in the media. In Oregon and Washington it can usually be boiled down to:

1) Taxes should be eliminated

2) All public services can be provided more efficiently by private entities than by government

3) We believe in legalizing drugs/same-sex marriage/some other currently debated social issue

4) Property rights trump everything else

5) There should be no governmental regulations, the free-market will take care of everything

6) Eliminate all governmental social safety nets

7) Privatize the roads

8) We’ll really only put effort into reducing or eliminating taxes, vote for us!

Really? If the KKK beats you up for speaking your mind, that wouldn’t abridge your free speech rights? I tend to think of the “right of free speech” as represented by Solomon Rushdie’s discretion to call upon the resources of the state, without limit, to fend off people that would attack him for his writings. That’s a whole lot of affirmative activity required for a “negative” right.

In contrast, government sometimes announces that it intends to refrain from acting. For example, it claims the right to “grant immunities” to its agents, or to foreign agents, or to “shareholders” in limited-liability companies. This simply means that government will not respond when private citizens call upon it to vindicate some private right that they would otherwise have. That’s an example of REAL negative action by government, yet I think of these policies as representing a huge intrusion of the rights of private parties.

Thus, I often find the distinction between “negative” rights and positive rights to be somewhat contrived.

Assuming that a libertarian wouldn’t object to a government-run school in the first place. I’m reminded of the old lady that scolds the libertarian for his beliefs. “You don’t believe in anything! Why, you wouldn’t see anything wrong with letting people have sex right in the middle of the public square!”

“That’s simply untrue, madam,” he responds, “I’m utterly opposed to public squares.”

it wouldn’t abridge your first amendment rights. the bill of rights doesn’t speak to this scenario. it prevents government from making laws that restrict your speech, but it does not mandate they make laws that protect individuals from violence if they speak…for an important reason.

democracy. its up to the people to decide if and how they want to punish the act you just described, ie assault. now, all states do in fact have laws agsint such an act, but these laws are not mandated by the first amendment.

theoretically, i suppose, a state could decide not to make assault illegal, but if they do they can’t do it selectively…either selectively on the basis of speech (1st amendment, value neutral) or on the race of the offender/victim(14th ammendemt, equal protectin clause).

rights exist outside of the democratic process, so the concept is very limited. these rights exist in order to, among other reasons, protect democracy from itself…like say the majority of people decide to put all the jews in a concentration camp. hey, that’s democracy. but not for the jews right. ergo, 14th amendment. lets say the republicans come in power an decide to outlaw all leftist thought. will of the people, right? well, thats the democratic connundrum: democracy undermines democracy. ergo, first ammendment.

but positive rights do no such thing. in fact they threaten democracy. to have positive rights (health care, housing etc) would be to take very important issues normally debated by the legislature and put them beyond democratic control.

and then you have a problem with power. these type of rights would, far from limiting the executive, presumably strengthen it, and thus leave the people at the mercy of the state.

PG,

I’m not a libertarian. I’m okay with takings power. I’m not okay with takings to enrich a private third party. If private businesses need land for their operations, they should negotiate directly with the property owners. If they won’t sell at any price, too bad. Put it somewhere else. New London wanted the tax revenue? That’s not a good enough reason to seize someone’s land and give it someone else.

A Chicago suburb that I covered was planning to seize a shopping center and turn it into a Super Target. To justify the takings, they had declared the area blighted. The reasoning behind the designation of “blight” was that the shopping center brought in much less tax revenue than the Super Target would. The shopping center was full. Every store was rented. The parking lot was always packed. But it was with stores owned by Korean immigrants, catering to the same population. The businesses did lower sales volumes than a Super Target would. Perhaps some of the businesses didn’t report all their income. If so, they should have been investigated on that front, not given away to Super Target. Do you really think a bunch of small business owners catering to a minority population that wasn’t represented on the city council at all is on equal footing with Target?

So … no, I’m not okay with the government taking private property that is “underperforming” in providing tax revenue and giving it to another private party that would be higher performing. And I’m not okay with the government abridging your property rights just to make another private entity richer.

But the basis of my objections isn’t that property rights are absolute and it isn’t that the government shouldn’t ever interfere in the economy. It’s based on how I define the public good. I don’t consider enriching one private party at the expense of another a “public good.”

So … heading to environmental regulations. Because we all bear the cost of environmental pollution or ecosystem degradation, I don’t think taking an absolutist view of property rights really makes sense. If everyone is being harmed by an activity on private property, I find that a pretty compelling public interest in regulating that activity – ahead of time, before harm that can’t be undone is done.

You probably could give an example that I would find too onerous, but I would need a specific example. I can think of examples where I think zoning regulations are too onerous and even counterproductive, but building codes and zoning save lives, as I am reminded every time an earthquake kills tens of thousands of people in a country with more lenient building codes (or more corrupt building code enforcement). There isn’t really a private sector mechanism for tenants to ensure that buildings are built in the safest way possible or that food is kept hot or cold enough or that fire exits open out (oh, don’t worry, when you all die in that fire, your survivors can sue and get reimbursed!).

PG,

In summary, it seems like you are arguing here that the only way to approach limits on government power is through the libertarian approach, and if you use a different approach, you’re either required to let the government do anything people would vote for or you’re being completely inconsistent. I think there are other approaches that arrive at, to my mind, more just and fair results, results that better reflect what I consider to be a proper balance between individual rights and state power. YMMV.

chingona:

of course there’s a middle ground between libertarianism and pure democracy…the system we have in place right now.

i agree with your analysis: the type of taking that occurred in kelo is open to corruption, and that was one of the big concerns of the founders. justice thomas’ dissent also highlighted the meaning of “public use”, specifically that new jobs and tax revenue does not constitute such.

furthermore, even PG concedes there wasn’t just compensation, which would make the kelo taking unconstitutional no?

i think the solution is all there in the document. takings are allowed but limited for public use. either scotus was too judicially restrained or didn’t philosophically believe in property rights in the first place.

Jake @ 33,

OK, if your beef is not with the Libertarian Party’s stated principles, could you link a statement, by Michael Badnarik or someone else who is as representative of the Libertarian Party as Bush of the Republican Party, that you consider to be an instance of “extremely simplistic, immature and stunted libertarianism”? Because when you boil down another person’s words, it is of course very easy to make that person sound simplistic and immature.

nobody.really @ 34,

I have no idea which laws against assault you’ve seen that apply only when the assault is to discourage someone from exercising their freedoms. And the Rushdie example is particularly poor because Britain doesn’t have very strong freedom of speech: their libel laws make them a popular forum for famous people who want to shut down criticism of themselves; they criminalize hate speech; they have no constitution that provides a right of free speech. I assume that they would have hidden Rushdie even if the fatwa had been declared because the ayatollah didn’t like Rushdie’s beard. In other words, what Manju @ 35 said.

chingona @ 36-37,

First, I should clarify what my position in this discussion is, as there seem to be several people who evidently are mistaking my posts about “this is what I think libertarians would say” for “this is what PG personally believes to be true.” As I stated in my very first comment on this thread, I don’t agree with libertarian philosophy overall, but I think it is not so ridiculous a belief as the cartoon might lead someone to believe. (Incidentally, I can imagine a social conservative taking the middle image of the fish who deny the need for a filter and using that as an argument against same-sex marriage.) I consider it a bit cheap for the weakest version of an argument to be the only version one deals with.

Second, while you may not consider higher tax revenues to be part of the “public good,” that’s pretty much the goal being sought when government increases tax rates, and taxation is a forcible taking of private property. Moreover, the “public good” is determined by democratic means, as I’ve described; if the city council is acting outside what voters consider to be the “public good,” the voters can vote against them.

Third, the environmental regulations that are most often argued by libertarians to be an uncompensated taking are not those that involve refraining from pollution that would harm humans, but those that require a piece of property remain wholly undeveloped and essentially untouched by humans in order to preserve a particular species of plant or animal from extinction. In order to satisfy what has been democratically determined to be part of the public good (i.e. maintaining a diversity of species), the government imposes regulations that have the effect of rendering property worthless to the owner, without even providing compensation for the loss.

Manju @ 38,

To clarify, I don’t know whether the compensation in Kelo was just or not. I have heard the argument from libertarians that because the government is the one deciding how much to pay, it’s inherently going to under-pay and provide insufficient compensation. If this is a problem, it should be addressed, quite possibly at the Constitutional level (i.e. the courts providing guidance on a fair way to determine just compensation). I don’t know what the correct market value for the properties at issue in Kelo was, nor what the government offered the owners.

“Right to have medical care provided free of charge” is not included in the quoted list, because all of those listed rights are negative rights, not positive rights. Most “freedoms” are generally framed as negative rights.

Oh, this is a bit of nomenclature that I have quickly come to despise – “negative rights” and “positive rights”. As if there’s something wrong or deficient with a requirement that the government stay the hell out of your way while you progress using your own resources and ambitions, but something blessed and superior to the government taking money and property from those who have earned it and giving it to those who have not.

This phraseology seems to have been invented to avoid calling a spade a spade. What is termed a “positive right” has been up to now called much more accurately an entitlement – a perfectly good word that communicates the content and consequences very well indeed. When people talk about healthcare and housing being rights, what they really mean is that they think people are entitled to them whether or not they have earned them. Regardless of whether or not you favor such a stance (and there’s certainly degrees, it’s not a binary solution set), let’s say what we mean instead of trying to hide it.

The founders of this country were well advised to frame our rights as they did. Emphasizing that citizens must concentrate on striving to become productive on the basis of their own resources and efforts is what it takes to build and maintain a country where the citizens are free. This is not to deny that we all have an obligation to aid those less fortunate than ourselves. But everyone’s first obligation is to help themselves. An emphasis on entitlements will weaken and destroy the United States.

President John F. Kennedy, a Democrat, put it well. “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” Would I love to hear another Democratic President say that today.

PG, the fact that the legal system has a process established to assign values and award compensation does not mean that the recipient is thereby fully compensated and made whole. There’s more to life than money. It seems to me that the system is more an attempt to solve the problem of “how do we equitably allocate a limited resource.” And while the concept of “punish them enough and they’ll stop doing bad acts” has validity and use, it does not make whole those already affected and those who’ll be affected down the line.

RonF,

I don’t think “negative right” has the connotation of “something wrong or deficient” that you’re trying to impose on the term, at least not among the political philosophers who use this terminology. If it sounds that way to you, OK, but just be aware that it’s not how it’s treated within the field. Nor have you provided any basis for your claim “This phraseology seems to have been invented to avoid calling a spade a spade.”

Also, I am well aware that “There’s more to life than money,” but I appreciate your patronizing delivery of cliches in the course of a discussion about competing political ideologies, including one that I’ve now said half-a-dozen times that I don’t agree with.

PG, you’re a libertarian? Really? When did you switch?

(kidding.)

I remember Kelo well, as I was living in the area at the time and knew quite a few of the players. Like many of these things, the winning team (Pfizer) was fairly well connected to a variety of quite powerful people, while the protesting homeowners were not. I am not surprised that they won, but given what I recall of the situation the homeonwrs got fairly screwed.

Real estate values are quite difficult to ascertain, as realty is unique. Much like your favorite sweater (worth perhaps $5 on the used market and worth perhaps $50 to you) homeowners may have attachments to their home which go above and beyond the desirability of that home in pure economic terms.

When calculating ‘worth” you have to use two competing values: (1) how much the owner would accept to sell it; and (2) how much an average buyer would pay to own it. #1 is difficult to find out so the courts lean towards #2. this generally screws over the homeowners.

Tax rates apply equally to every property that falls into a particular taxation category. Eminent domain involves the complete seizure of one particular property.

The thing I really object to in Kelo, and I’ve tried to be clear on this but maybe I haven’t been, is that they wanted to take private property and give it to another private party. I don’t oppose takings across the board, and I don’t oppose government involvement in economic development. But I have a serious problem with the government using its takings power to the economic advantage of a third party. You don’t. Fine. But the issue isn’t that I don’t understand what’s involved or have some confusion about what taxes are. I just don’t consider the benefit to be obtained to be important enough nor appropriate enough to government’s role in economic development to justify impinging on a private property right. Property rights aren’t absolute, but the government ought to have some compelling reason to impinge on them. I don’t think getting rid of an under-performing division of the community is compelling enough, even if people did vote for it.

I know this, and actually was going to get into it and then stuck with the pollution example upthread because it’s what everyone had been using. I think property owners in these cases have a legitimate claim, but I think the value of preserving habitat is high enough that we need to look for ways to deal with endangered species that don’t just say “whatever, it’s your property.” In some cases, offering to buy the land or otherwise compensate the owner would be appropriate. They are giving something up for a public good. (Was I supposed to say otherwise and reveal something about myself?)

The county I live in has a regional conservation plan that designates certain areas as high resource value (for habitat, riparian area, etc.) and others as medium or low, with increasingly stringent set-aside requirements as the resource value increases. The requirements can be satisfied by buying land off-site that is of similar resource value (though you have to buy more acres off-site than you would have to set aside on-site). And they only kick in when someone comes in for a rezoning. There is an impact on their property value, because a lot of times the existing zoning is outdated, and the rezoning (from say, rural residential to commercial) would be a cakewalk, but if they stick with the existing permitted uses, they don’t have to meet the new requirements, so there is no regulatory taking. You aren’t actually entitled to a rezoning.

What’s special about this plan is that it constitutes regional compliance with the Endangered Species Act (covering, I think, two endangered species and a dozen or more threatened species), so individual property owners and developers don’t have to take their individual parcels to the feds, and there’s a lot more certainty for the development community. If you don’t want to do the set-asides, you know where to buy – the low-resource-value areas, which are clearly laid out on maps developed by the county with wildlife biologists. If there is no way to make your project work with the set-asides, you can buy land off-site. They’re also working on transfers of development rights and land swaps. So there are ways to do this that don’t render property worthless, still allow for development, protect habitat, and don’t bankrupt the government by requiring it to simply buy up everything that has any resource value.

I’m not sure how a libertarian would view such a scheme – it’s pretty regulation intensive – but nonetheless, it does balance the public good of conservation with property rights.

And PG,

I understand you’re not a libertarian – I saw right where you wrote it the first time, and I’ve read enough from you that, well, I know that about you. I felt like you were trying to push any concern about government infringement on property rights into the libertarian box, and that’s what I was objecting to. But if all you’re saying is that people should engage with more than the weakest libertarian arguments, then I misread you.

First, Thomas’s argument that the 5th amendment provides for taking for “public use”, not “good.”

Be that as it may, to allow for the govt, or the people, to define public use/good however it likes is a circular argument. In other words, your saying the 5th limits takings to those that are done for the public good, but the taker decides what is good, not the judiciary. In that case, then how exactly is this part of the takings clause a limit on government?

Makes more sense to say what constitutes public use/good is up for judicial review, though it might be fair to say the burden of proof is on the property owner because, all things equal, what a democratically elected govt does should be presumed to be the will of the people. But all things aren’t necessarily equal.

Very well put. This would make a great T-shirt and I completely agree.

I was not a fan of the Kelo decision. I’m still not.

From my perspective, eminent domain is a necessary and good power of the government, right along with condemnation. The question becomes whether it should be used when the primary benefit is to a private party, and the public benefits are incidental to private gains.

I am of the camp who believes that if it is “public enough” to justify the use of eminent domain powers, then it should also be “public enough” to require government involvement with the project directly. I think that the only people who should be able to be the direct recipients of eminent domain should be (1) government, and (2) public charities, which are regulated by government.

Once the government owns it, it can of course bid it out for private development.

On that same vein, the “old” process would be:

1) government votes to acquire property through ED.

2) government acquires property

3) government votes on what to do with it (may or may not be in this phase, but it happens somewhere.)

4) government bids it out through standard procedures

5) the building commences.

What private eminent domain does, is to let an elected body functionally combine steps of the process. In one fell swoop, you can vote on (a) taking for eminent domain (b) to give to Pfizer, (c) to build a research center. IMO that reduces review and oversight, and it reduces the voter’s right to influence the process.

I don’t dislike kelo because I’m a libertarian, i dislike it because I think it allows for more disconnect between voters and elected officials.

What is the libertarian mechanism for avoiding extinction?

—Myca

What would the libertarian mechanism be for avoiding extinction?

People who don’t want to see the extinction happen, paying for whatever needs to be done to prevent it.

Ah, so there isn’t one, really.

Is that about right, PG?

—Myca

Er, didn’t you read Ron’s comment? Because he described one. You may not like it, but it’s there.

From a libertarian perspective, the existence of an animal has value just like anything else, and you can put money on things you value. If you want spotted owls to have forest habitat, buy some forest and leave it standing. If you aren’t willing to pay for it yourself, then you shouldn’t be able to force other people to pay for spotted owl habitat. If you think there is value to spotted owls remaining in existence, it is incumbent on you to define that value to other people in a manner which will also get them to chip in.

So if it costs $100 million to preserve sufficient habitat, then what? You can probably find 100 million people worldwide who will claim that they care, and who will claim they will be upset if the owl goes extinct… but you may also find that very few of them are willing to actually pay any of their own money to save the owl. Having worked for PIRG in the past, this is pretty standard.

Obviously that method doesn’t work in all situations. But AFAIK, libertarians don’t reject the tragedy of the commons. As such, there might possibly be situations where preventing the extinction of an animal might require some government intervention if it were in a limited class of providing a public good as libertarians define that good.

This may be a better explanation:

Bob owns land which is the last known dodo habitat. Bob wants to clearcut it. Dodo-lovers want it to stay as it is. What happens? There are three basic options.

1) A majority votes to amend the zoning/conservation laws so that Bob is prevented from clearcutting his land. Bob is not compensated for the change in permitted use. Therefore Bob will personally bear the cost of the zoning change and reduction in value, as imposed by the majority.

2) A majority votes to amend the zoning laws so that bob can’t clearcut his land, but ALSO to raise taxes so that everyone chips in to compensate Bob for the reduction in value of his land.* All citizens will share the cost of the zoning change and reduction in value, as imposed by the majority.

3) A group (majority or not) who likes dodos gets together and pays Bob in exchange for a restrictive easement which preserves the habitat. Although not all interested citizens may contribute to the cost, all of those who contribute to the cost do so voluntarily.

Generally speaking, we currently tend towards #1 . Many people in the country–including those who do NOT call themselves libertarians–are more comfortable with something like #2. libertarians are probably espousing #3, though most of them who I have met would be a hell of a lot happier with #2 and would probably settle for it in a heartbeat.

*For the purposes of this example, I’m assuming that value and compensation can be easily calculated.

Well, no, that’s my point, is that that’s not really a mechanism, that’s “figure it out yourself.”

And, see, this is precisely the flaw in libertarianism. They don’t have a decent mechanism for dealing with distributed harms to the public good.

Nobody owns the species ‘spotted owl’, so nobody has grounds to bring suit if it’s destroyed.

You could make driving any species to extinction illegal, but then the question is what do you prosecute? Habitat destruction? Then you’re back in the same boat you were in before, with regulation of private property. Killing any spotted owl? That’s awfully similar. Literally killing the last spotted owl? Leaving aside how fucking stupid that is, it’s also impossible to really know in most cases.

And yet … plant and animal extinctions are, I believe, a pretty clear harm to the public good, in that it’s the destruction of something that the larger community derived a benefit from, either to a larger or smaller extent (depending on the plant or animal in question, of course).

Another example of this kind of problem: antibiotics. It is in the self-interest of individual people in general to take a bunch of antibiotics for whatever problem they’re facing. The overuse of antibiotics, though, breeds antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The effectiveness of antibiotics is a public good, and one that needs preserving … but when you get an antibiotic-resistant infection, who do you sue? It’s a collective problem that has only collective solutions.

You run into similar situations when you talk about pollution. Within a 30 mile radius of where I live, there are five oil refineries. Four within 20 miles. Three within 10. Two within 5. If I get sick from the air I breathe, or the water I drink, even if I’m able to prove that the illness is due to industrial pollutants from a refinery (no mean feat on its own, and one which puts the expense on the victim), there’s no way to know which one it’s from … and it’s likely that they’re all polluting a little. Hell, let’s say that none of them individually are polluting enough to make me seriously ill, but the aggregate effect of all of them polluting might very well make me ill.

Well, who do I sue in that case? All of them can argue that their emissions weren’t enough to cause the harm, and they’d be right. That’s the problem. It’s not an individual problem, and it doesn’t have an individual solution.

—Myca

Sailorman:

Me:

Or putting it another way, there’s nothing in libertarianism that addresses collective problems other than, “I guess people will take care of them if they think they’re important.”

The ‘mechanism’ as far as that goes is, “we won’t stop you.”

Which, when it’s a collective problem, is just as vulnerable to the tragedy of the commons as any other collective issue.

—Myca

If you believe that markets are efficient, then presumably — since the fact that the government sometimes limits land use to protect wildlife is well-known, and has been for decades — the existence of environmental protection laws (and the potential for new laws) has been suppressing the price of land generally, and wildlife areas specifically.

So do keep in mind that Bob has already benefited from the existence of environmental laws, which made it possible for him to buy this land at an artificially lowered price, in exchange for the risk of losing his investment if it turns out to be the nesting ground of the last remaining dodos. (And really, shouldn’t he have had the land appraised before buying?)

There isn’t a libertarian in the world who feels that the government should bail out poor people who make bad decisions.So Bob who owns huge acres of wildlife takes a bath — that’s sad, but Bob knew the risks before he bought the land.What Bob should have done is taken the money he saved (because environmental laws artificially lower land prices) and used that money to buy insurance, so that if this exact thing happened he’d be covered. Why should taxpayers pay for Bob’s foolish risktaking?

At least here in Oregon, Libertarians don’t limit themselves to these sort of examples when they create laws to prevent “takings.” They talk about any sort of case of a government regulation lowering the value of a land, including limiting the profit that can be made from that land.

PG:

As a recent convert to the “non voter camp” I’m curious what made you change? To me I’ve seen a lot of truth (maybe not everything though) in what libertarians have been pointing out in governmental shortcomings. This is especially true when it comes to spending money (at least in my opinion), specifically bank bailouts that suck, out of control military spending, and so forth.

Myca:

I think that’s a fair way of putting it. So the question I guess then is which is better at addressing collective problems the government or “the market” (is that the term for it?)?

The government. IMO, that’s one of the main reasons that governments exist: to take collective actions which are necessary for the public good and/or which provide a significant public benefit, in situations where individual incentives don’t work.

The devil is in the details, of course, and it is hard to find the proper line between too little and too much government intervention.

I am not sure such insurance is available. You can certainly insure against something that already exists, but I have not heard of property insurance designed to insure against democratic action which isn’t even up for a vote yet. You’d run into moral hazard there, I think.

But in any case, the underlying issue remains the same: whether it’s a risk or a cost, there is a group of people who have a view on dodo protection, and they are enforcing it and not paying for it. Bob is holding the bag.

Furthermore, you are presupposing that Bob knew that dodo protection was even an issue at the time he bought the property. Often that is not the case. When I live we have zoning issues which weren’t even on the table two decades ago and which are quite serious now. It is unrealistic (actually, almost impossible) to suggest that people buy insurance against all unknown and future hazards of any type for as long as they own the property. (and it’s inefficient as hell. You may as well go with my #2 example instead.)

*Moral hazard is when the existence of a safeguard (in this case insurance) increases the tendency of someone to use that safeguard. IOW, the safety mechanism makes unsafe behavior more likely, just as you may be more likely to speed if you are wearing a seatbelt. In this case, the restrictions would probably tend to end up being applied to insured properties, since uninsured owners would put up a bigger fight.

Sailorman,

I’m curious about something. Your description of land use regulation infringing on property rights seems to assume situations in which your zoning is changed after you bought your property. In Arizona, they can’t do that, not without your permission. There have been a handful of cases where they tried to downzone property that was particularly environmentally sensitive and lost in court. It’s problematic here not just from an environmental perspective but from a what goes where perspective. Most of the zoning was laid down in the 1950s and allows for all kinds of uses that would never be allowed in the same vicinity today. Is that not the case in Massachusetts? They can just rezone you to whatever they feel like at any time? Or what?

Edited to add: I understand the Endangered Species Act can kick in whenever evidence of an endangered species is found, so it’s a bit different. It seems that maybe part of the problem is that it isn’t explicitly a land use regulation but ends up being one in practice. But that’s one of the things about the regional plan I described in my long comment @ 44 – because we have regional compliance, you could legally kill an endangered species as you develop your property.

Sailorman:

I agree that’s the basis for why government exists. I’m unsure though whether “the market” or government operates better for the collective benefit of all. I wonder what makes you so convinced one way or the other?

Your point raises more questions though. Who defines the public good/public benefit and how to go about achieving it (within the context of government)? What about abusive actions done in the name of public good/public benefit?

The people, democratically. If the government takes an action that they dislike, they have the option of democratically changing that action.

What about abusive actions done in the name of private good/private benefit?

At least I have some kind of say in what my city government does. When I go in to talk to the mayor, she may not do what I ask, but she’ll at least listen.

The Chevron board of directors? Not so much.

—Myca

You generally have a grace period, but yes, they can change zoning and have it affect you even though you owned the property prior to the zoning change.

You’re different? Huh. How do they really do zoning, then?

If the government acts to solve a problem, private individuals can still act. So only the “government act” situation offers two discrete methods of solving a problem; the “individuals only” situation does not.

The question really then becomes whether the government intervention is (a) actually negative in effect; and/or (b) overly stifling the individuals’ attempts to do things.

Myca

A legitimate question. Clearly there are abuses with both. So, which one abuses more/worse? I dunno, which is why I find libertarian and socialism positions interesting.

And see that’s where I get lost at, I don’t feel as if I (or for that matter any other citizen) has much say in our government. Even when we do vote in the politicians we want they often don’t do what they were voted in for (war in Iraq is a great example). I feel I have more say in what happens in the market than I do with government. This is especially true when I think of all the instances where government officials have listened to/voted in by the wrong people.

Obviously, we have more say the smaller the scale is. I live in a town of <30,000 residents, so when I go in to speak to the mayor, 1) she’ll see me, and 2) I represent a sizable portion of the people she’s talking to today.

When we talk national level politics, it’s a lot harder for one person’s opinion to make a difference, since it’s obviously diluted by the opinions of everyone else.

Goodness, I have no idea why. I wouldn’t be surprised of more people shopped at Starbucks last year than voted in the last presidential election … your opinion is more dilute still. And that’s even before we get into large multinationals like Chevron.

Additionally, since corporations are 1) answerable to their shareholders, and 2) reliant on the profit motive, your opinion carries even less weight if you are not a shareholder or advocate a course of action that might lower profits. This is not true of democratically elected governments.

Well, sure, but such are the perils of democracy. There is a pretty good way of making sure that governments only listen to the ‘right’ people, though! It’s called fascism, and historically, it’s record is … er … well, let’s just say ‘mixed.’

—Myca

Myca,

But the private sector is going to have more trouble following the Rove strategy of 50%+1. If Starbucks takes actions that cause 49% of the population to loathe it, they’re going to run into trouble, because almost certainly that 49.9999% will include significant numbers of their target market (people who can afford $4 for coffee). If Starbucks at any point had the kind of unpopularity numbers that Bush had in the last year of his presidency, it would do everything it could to reverse that, not shrug and say, “Well, history will be on our side.”

The private sector relies tremendously on the general good-will of regular people. Why do you think that morning show that was hateful toward trans-kids had to reverse itself? Its sponsors couldn’t afford to be associated with hatefulness. Losing even 25% of a customer base is a disaster for someone in the private sector, because the private sector is generally competitive.

If you live in a town of less than 30k, I don’t think Chevron or any other corporation that has more employees than your town has people is very analogous to your local government.

AND it’s before we get into situations like large multinationals operating in third world nations where those primarily affected by their actions are often not their customers. In a situation like that, the corporation has close to zero incentive to listen to the opinions of those that their actions are primarily affecting.

—Myca

Myca:

If a majority of people are for mandatory press censorship by the government it would be a public good? The gay marriage ban is apparently a “public good” in most states. If you can convince enough people of anything, it is considered a public good. In fact, since most people are OK with torturing terrorists, maybe thats a public good.

This and PG’s similar view that –

– is the reason that our bill of individual rights supercede (or should) all other authority (state, federal, or mob). If we have freedom of the press, speech, arms, property, etc. It should be an absolute limit on the power of government, or any voting mob, to circumvent remove those rights. (yes, “fire in a crowded…”, “reasonable”, etc. the like not withstanding)

So on a whim, when “public use” changes to “public benefit” without a constitutional amendment, it subverts all of our rights. Because if your individual rights depend on the mood of nine robed lords on the bench we can only be on the slow march to tyranny.

Ah, except that I live in a town in which large corporations, in the form of oil refineries, have a huge presence. The question is: if I want ‘X’ done, which would my time be better spent on:

1) Persuading the corporation to do it directly?

or

2) Persuading the local government to make the corporation do it?

For me, the choice is obvious and clear.

I think that this also holds true on a national level. Although there’s something to be said for directly lobbying a corporation to improve its safety/environmental record, generally there have been better results across the board by lobbying the government to set up standardized regulations.

—Myca

You’re different? Huh. How do they really do zoning, then?

My knowledge of zoning comes from sitting through dozens and dozens of planning and zoning, board of adjustment, village board/city council/county supervisor meetings over the last decade. So I’m not an expert in land use law, but I’ve talked to a lot of planners, land use attorneys, developers, community activists, covered a lot of development controversies, and I have a decent sense of “Hey, they can’t do that!” and “Well, there’s probably nothing they can do about that.” And I’m pretty familiar with various theories, legal principles, precedents, etc. I’ve worked in Illinois and Arizona, and I don’t remember Illinois being radically different. That said, Illinois is far enough in the past that I’m not comfortable going to the mat about Illinois land use law.

Here’s how it works in Arizona. There is planning, and there is zoning. Planning is the government’s theoretical idea of what they’d like to see happen with your property. Zoning is what you can legally do with your property. They can change your planning designation without your permission. They can’t change your zoning without your permission. Zoning is often outdated, which sometimes works in the property owner’s favor, allowing him to do something with the property that would not be allowed if planners (and the neighbors) had their druthers. Sometimes, the zoning doesn’t allow what the owner wants to do, and the owner requests a rezoning. Rezoning is a discretionary, legislative act, so you aren’t entitled to it, and if you’re turned down, your property rights have not been infringed at all. That said, if your re-zoning request is in line with the underlying planning designation, you’ll probably get it, and the government will have to provide more justification for turning you down. If your rezoning request doesn’t match the underlying planning designation, you probably won’t get the rezoning.

So changing the planning designation does have an impact on your property’s development potential, and they can do that without your permission because it doesn’t change your existing rights. But your zoning – the legal designation of your permitted land use – cannot be changed without your permission.

Now, they have tried to downzone property. But when it’s gone to court here, they’ve always sided with the land owner against the government. This is the West, and we like our property rights out here. So it could be that it’s more a matter of state case law, leading to governments just not going there anymore, and that could be why it’s different in Massachusetts. At the same time, I’ve read appeals court decisions here that sided with property owners that took into account court decisions from around the country. That makes me think we aren’t too far out on a limb here.

So … more than you wanted to know about zoning.

Oh, and rezoning is generally what makes new regulations kick in. If you don’t ask for a rezoning, rules that were passed after you bought your property won’t apply. But if you want a rezoning, you have to come into compliance, just like a major renovation will trigger new building code requirements.

Okay, so comparing Supreme Court Justices to Nazis is ‘invoking Godwin’.

I don’t believe I’ve ever seen them compared to nazgûl before, though!

Clearly, we need a new word.

—Myca

Myca @ 70,

Do you generally find that if you want someone to do something well, truly and thoroughly, that you’re better off persuading that person directly, or that you’re better off finding someone who controls that person and having them tell that person to do it?