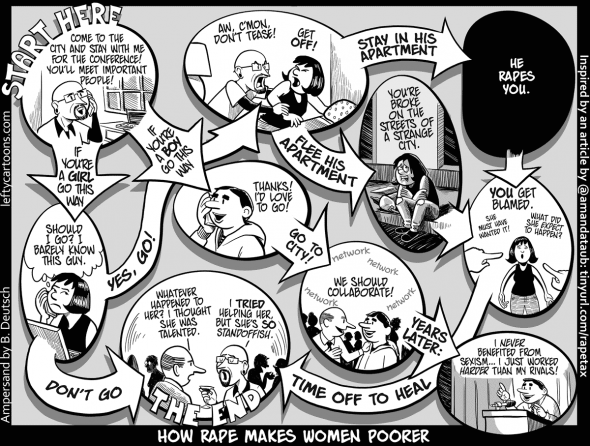

This cartoon was inspired by “Yes means yes” is about much more than rape, by Amanda Taub.

Transcript:

The cartoon is in flow chart form.

Panel 1 is labeled “START HERE,” and shows a fashionable hipster man talking on a cell phone. He has a Van Dyke beard.

VAN DYKE: Come to the city and stay with me for the conference! You’ll meet important people!

An arrow labeled “If you’re a girl go this way” leads to a panel showing a young woman on the phone thinking “Should I go? I barely know this guy.” There are two paths leading from this panel: “YES, GO” and “DON’T GO.”

“DON’T GO” leads to a panel marked THE END, where we see an IMPORTANT PERSON IN A SUIT AND TIE speaking to VAN DYKE.

IMPORTANT PERSON: Whatever happened to her? I thought she was talented.

VAN DYKE: I tried helping her, but she’s SO standoffish.

THE END!

“YES, GO!” leads to a panel of the young woman and Van Dyke in a bedroom. He is grabbing her and she’s trying to fend him off.

VAN DYKE: Aw, c’mon, don’t tease!

WOMAN: Get OFF!

There are two routes out of this panel: “STAY IN HIS APARTMENT” and “FLEE HIS APARTMENT.” “STAY IN HIS APARTMENT” leads to a black panel labeled “HE RAPES YOU.” “FLEE HIS APARTMENT” leads to a panel of the young woman sitting on a sidewalk, shivering, in the dark, labeled “you’re broke on the streets of a strange city.” Whichever path you choose, they both lead to…

A panel marked “YOU GET BLAMED.” Fingers point at the young woman.

FINGER 1: She must have wanted it!

FINGER 2: What did she expect to happen?

The “YOU GET BLAMED” panel leads to an arrow marked “TIME OFF TO HEAL,” which in turn leads back to the THE END panel.

Going all the way back to the “START HERE” panel, there’s one more route in this flow chart. From “START HERE” (“Come to the city and stay with me for the conference! You’ll meet important people!”) choose “IF YOU’RE A BOY, GO THIS WAY.” A young man on the phone says “Thanks! I’d love to go!” We then see him at a party in the city, with lots of networking going on; the IMPORTANT PERSON is saying to him, “we should collaborate.” An arrow marked “YEARS LATER” leads to a panel of the now less young man, clearly now an important person himself, giving a speech at a podium.

YOUNG MAN: I never benefited from sexism… I just worked harder than my rivals!

I work in academia (as do several others in this thread), where relationships among coworkers are relatively common. (I will leave as an exercise for the reader if this is because nobody else will have us. :D) But it’s also really common for academics to hang out socially outside of working hours, and I can’t think of any relationships among the people I know that happened solely because of work interactions. And, as a rough guess, the occupations where people spend the most time at work are also the ones that are most likely to have socialization with colleagues off the job as well–partially because it’s harder to make friends when you spend all your time at work. In other words, the workplaces where this kind of policy would have the most restrictive effect (because of the amount of time being constrained) are also the ones most likely to have alternate avenues of interacting with the same people.

(As La Lubu says, the heterosexual relationships can have a more negative impact on the women involved: if the pair are in closely-related fields some people have a tendency to see the work of the woman as aided by the man, which is pretty annoying.)

It’s not true of everyone, I agree. But I think that the people who find it hard outside their workplace, also tend to be the people who find it hard within the workplace. And some (not all) of the folks who find it hard, are also folks who have trouble perceiving social cues, which means that they will have a harder time recognizing when their advances are unwelcome. I’d argue that for people who have trouble perceiving social cues, a firm rule – “just don’t ask anyone out at work, ever” – is actually beneficial, because it’s much more comprehensible than informal social rules are.

This is hyperbole, I assume? Because I don’t think there’s anyone who favors a “no flirting, anywhere” rule.

La Lubu:

There seems to be a misunderstanding. Your point here misrepresents the disagreement as a false dichotomy. There isn’t a necessity to choose between your rule of ‘no asking people out at work ever’ and ‘no rules at all’ and apply it consistently to all workplaces.

Dealing with queries about yourself from other people might not be part of your job description but it is a basic part of being a civilised human being. As is treating people with dignity and respecting their communicated boundaries. It’s more than possible to ask someone on a date while do this.

If we go back to what you said in your comment@18:

These things are in breach of the latter principle. As far as I understand it, (a) fits clearly under existing sexual harassment defintions, while (b) and (c) if repeated/on-going could be used to demonstrate a hostile work environment, which would also fall under existing sexual harassment defintions.

If employers are blaming women for the conduct of the men then that is also pretty clearly sexual discrimination and already against the existing rules/defintions. Fibi@87 lists other categories of things which are already against the existing rules/definitions.

If these things are still occuring then clearly there is an issue with the enforcement of the current rules and not with their scope. I don’t see how drastically increasing the scope will improve enforcement. I haven’t seen any examples of genuine problems in this thread that I wouldn’t see as being covered by existing rules. If you think I’ve missed any feel free to point them out. It wouldn’t suprise me if politically motivated actions to address issues have done both and thus muddied the waters as to whether it was the change in scope or enforcement that caused the effect.

You’ve described some experiences with pretty poor employee/employer conduct. It’s quite possible that the culture at those workplaces is bad enough to justify a strict policy in order to bring about change. However, I don’t think there’s evidence to support a claim that workplaces generally have such a problematic culture, nor do I think its reasonable to apply policies that may appropriate for some subset of workplaces universally to all workplaces.

I was actually thinking of using religion as a example as per gin-and-whiskey’s comment @99. However, let’s consider a couple of other examples of you “just want to do my job and not have to put up with other people’s crap” logic.

Politics:

Problem: Alice has political views that differ significantly from many of her coworkers. When politics is mentioned at work things often result in heated arguments. Alice’s boss considers Alice at fault even though she’s just trying to calmly express her opinion and others react aggressively. Alice’s colleagues consider her morally bankrupt regardless of how she expresses her views.

Solution: Ban all political discussions, in all workplaces everywhere. You can discuss politics elsewhere and people need to work without facing a hostile workplace. That presidental election that occurs tomorrow? Not allowed to talk about it. That war that just started? Discussion about it is off limits, even just around the water cooler.

Family:

Problem: Bob is single and doesn’t have kids. All Bob’s coworkers are family types and spend the day chit-chatting about their kids, what they’re doing at school or what they did with them over the weekend. Bob’s coworkers consider that Bob wastes his free time on silly juvenile activities. As a result Bob is expected to always do the unpaid overtime to get things done because as everyone knows the others all have important ‘family commitments’. Bob just wants to do the same job for the same pay as everyone else and not face ridicule at work for his life choices.

Solution: Ban all talk about kids and family at any workplace. You don’t need to discuss your kids at work, and people need to get paid without facing a hostile workplace. You or your partner just given birth? Nope, sorry, talking about it is off limits. Got a sick or misbehaving kid and want some friendly advice? Don’t care; bringing that up might interfer with someone’s right to work unburdened by social issues.

Diet/weight:

(and La Lubu, since I don’t agree with SomeOne and don’t want to be confused, would you mind using names next time?)

Sorry! Will do. I was lax in the quoting because I was in a hurry to get out the door.

I’m asking you to define what you don’t want.

I do not want to be asked out on dates at work. I don’t want to hear come-ons or comments about my body at work. Is that clear enough for you?

Asking your coworkers if they want to come to church? Publicly reading your religious texts in the break room? Praying with your like-minded coworkers before eating lunch?

gin-and-whiskey, apparently I used a bad example. You and I must live in completely different worlds. Tradespeople in the rust belt are a non-religious lot; largely religious “nones” (mostly younger people; raised with no religion) or lapsed Catholics (“wedding and funeral” churchgoers, rather than “Christmas and Easter”). People aren’t hostile to religion per se, but are very hostile to proselytizing—I suspect because the legacy of ethnic/religious exclusion in the trades hasn’t been lost to memory yet. Re: Hobby Lobby, well, when they were in the news there was a sizeable protest against them in my city; of the hundreds of cars that passed by, most gave us “happy honks” and thumbs up, claps, “hell yeahs!”, etc. Just sayin’.

At least I think so. There are a ton of male-male interactions which are non-easygoing, non-congenial, non-collegial, and which contain a shitload of sexual expectations and/or assumptions. “Treat me just like you would treat a male colleague” and “treat me nicely” aren’t the same thing, at all. Men are often not very nice to other men.

I hope you realize how patronizing this is. I’m talking about actual experienced, observed conditions on my jobsites. I’m talking about real-time interactions that I observe and participate in. I’m not talking about “nice” (whatever that means). Put a sock in the “mansplaining”.

if the pair are in closely-related fields some people have a tendency to see the work of the woman as aided by the man, which is pretty annoying.

Worth highlighting.

desipis:

In all of those situations, it would probably be appropriate to ban the discussion at that specific workplace because it has been known to cause problems. (My exception would be Bob’s case, but–at least for me–in that case I think the imposition is much greater than the others: not talking about your family is entirely different from not talking about food.) When we’re talking about workplace sexual harassment, though, this is a case where many many people in many different industries and many different working conditions have experienced a problem. It’s not a one-off, or even a rare, occurrence (though thankfully getting rarer). So proposing that workplaces adopt similar regulations, because they’re all likely to see similar problems, isn’t at all the (eta: unfoundedly) strict measure that your examples would be.

(I’m not sure you’re thinking this, but just because it’s a possible interpretation of your examples: I don’t think anyone is proposing barring workplace dating invitations because they think it will completely stop the problem of sexual harassment; rather, the dating invitations are themselves a problem. Similarly, the fact that Clarence in your examples gets overlooked for tasks and promotions probably will need a separate intervention as well, but stopping the constant comments about his weight is a suitable goal in itself. Etc. And if you didn’t mean something like that by the examples, er…I guess I’ll leave this comment for the other readers? :) )

Amp wrote:

I assume you are probably right that almost everyone, including La Lubu, who is calling for an expanding the type of behaviors that are considered harassing leaven that with a realistic expectation that initial infractions are treated as minor offenses. However, in practice – at least in America – that is something that would be close to impossible to implement.

For right or wrong our harassment laws don’t actually make it illegal to harass someone (in most cases). They make it illegal for an employer to allow someone to harass someone else. A case can be made against an employer for a hostile environment even if no individual employee engaged in persistent harassing behavior — essentially no individual deserves more than a “relatively minor punishment” but the company is legally on the hook for major damages.

Obviously, that’s not tenable from the employer’s point of view. Which is why, under existing law, companies crack down hard on minor offenses which are brought to their attention. If we make any unwelcome request for a date a “minor offense,” employers are going to treat it as a major offense (they just have to).

Which is why I can support much of what La Lubu says in terms of policies that an individual company may want to put in place for their workplace (depending on factors like man/woman ratio; amount of professional socializing after hours; annual turnover rate; etc.). But if we codified it into law and required all employers to adopt it there wouldn’t be any leniency for first offenders.

Crystal. Thanks.

Re: asking out on dates:

The issue with is that rules which stop the first, unknown, request are required to be much more intrusive w/r/t personal interactions than rules which stop the second, “known to be unwelcome,” request.

Most existing rules prevent the second request already, assuming that the askee gives clarity: there is a difference between “do not ask someone out more than one time” and “do not ask someone out if they have told you not to ask them again.” I don’t oppose those rules. I don’t oppose better enforcement of those rules, if they’re not being enforced–and it sounds like they aren’t. I don’t oppose punishment for violators.

I do oppose rules which try to stop the first interaction, because I think those rules are very difficult to do right and because they lead to all sorts of problems. More to the point I think that the vast majority of the benefit that you might seek by implementing more restrictive rules would be better achieved through proper enforcement of existing rules.

I agree that the “don’t do that again” issue also puts a bit of a burden on the woman. I’m OK with that: the goal is to set up a system that is largely designed to change the behavior of men, and in which men will required to make a lot of changes to their behavior or risk getting fired. In that context, the limited burden that you have to say “please do not ask me out again” in order to prevent someone from asking twice, does not seem unreasonable.

Re come-ons:

TO the degree that they are “HOT TITS” I think we have no disagreement. To the degree that they’re basically the equivalent of a request to go out with someone I think they should be treated the same way.

Re: comments about my body

These are actually much trickier, because people talk about other people all the time. As a result attempts to ban this can often lead to a situation where the problem lies in the speaker, not the words.

If your pal Julia sighs in envy and says “man, La Lubu is always so hot looking and dressed so well” should she be fired? If not, it’s very hard to write a rule where Matt gets fired for saying the same thing, even if you think Matt is totally gross and sexist and even if you shudder at the sound of him saying your name.

I don’t think that people shouldn’t be upset by it. I’m just pointing out that trying to control what is said TO you is a lot more achievable than trying to control what is said ABOUT you.

Lol. Seriously? If you were looking for misuses of “mansplaining,” then “a man objecting to the accuracy of a woman’s summary of how men act to each other” is probably at the top of the list.

Heh. “Mansplaining” my foot. If anything this would prompt one to invent the term “femsplaining.”

I haven’t yet heard anybody in this thread advocating for a law of this nature.

Yes, in fact I thought the discussion was specifically about morality, rather than about what the law should be?

Harlequin quotes me and replies:

True – the conversation may have drifted a bit, but looking back nobody is advocating changes in the law (or the case law). Everyone is either talking in general terms or talking about individual employers changing their policies.

And on that, I am in agreement. An employer should certainly be free to restrict by policy personal interactions that harassment law doesn’t. And there are some times when an employer should do so.

gin-and-whiskey, the problem with your desire to draw a line between what you perceive to be a harmless level of intrusion with what what you perceive to be a harmful level of intrusion is its ahistoricity. You recognize certain behaviors as clearly harmful and beyond the pale because of decades of complaints, lawsuits, workplace actions, and political action by women that have changed general workplace culture. The general acceptance of routine quid-pro-quo requests for sexual intercourse is something that is well within the lived experience of most of the people participating on this thread (albeit secondhand, through our female relatives and the mass media, as most of us were not of working age during the heyday of sexual harassment). There were few women employed in the 1970s that didn’t endure extreme levels of sexual harassment in the workplace. If we were having this conversation forty years ago, you’d be telling me that a little pat on the ass never hurt anyone, and that while you’d be ok with some guy getting a good talking to by his boss for continuing to touch my ass despite multiple rounds of “get your hands off my ass!”, it’s unreasonable to expect men at work to keep their hands to themselves without getting at least one free squeeze.

You apparently were sleeping when I stated that what you regard as harmless requests for dates change the workplace dynamic. Most of my male co-workers treat me differently after they observe what you regard as a harmless flirtation or date request. They’re colder. Distant. Quieter. What was previously a friendly, “brotherhood” environment becomes something else. They lose trust in me. They lose trust in me because what-just-happened highlights what they—my male co-workers—perceive to be an advantage I have that they don’t. The term of art in my world is “pussy power”. After what you regard as a “harmless” flirtation, I’m watched like a hawk to see if I plan on leveraging “pussy power” as a means to get ahead, get a plum job assignment or easier duties, stay employed when the layoffs start happening, or even quitting my job entirely to have some man earn my living for me. This, after an over 25 year track record of never doing any of the above. It’s depressing. Depressing hell, it takes a piece out of my heart.

And y’know, I have a really good reputation in my Local. Not to brag (but yes! to brag! LOL!), I’m held in high esteem. If you ask any random brother if I was the kind of woman who uses her sexuality to get ahead, they’d look at you as if you’d just grown two heads and then set you straight.

But in that moment? After some other random guy figures he’ll take his chances and ask, ‘cuz what’s the worst that can happen—that I’ll say no? It isn’t the frontal lobe that’s doing the thinking—it’s the lizard brain. I’m now seen by my co-worker(s) as a threat, even though that wasn’t the intention of the random guy doing the asking. And I’m left to deal with the fallout. Of proving myself, over again. And it’s worse when jobs are coming to completion, and the shop has not much on the horizon, so everyone knows there’s going to be layoffs—-they just don’t know when the hammer’s gonna start falling or who it’s going to land on first. Even some random dude from a different trade, or some delivery guy, or some employee at the building that we’re working in—someone with absolutely no connection of any kind to influence anything about my employment—doing a so-called “harmless” ask, is going to impact the way my co-workers see me. I go from sister to potential traitor thatfast.

This isn’t unique to me; it’s a popular topic of conversation among tradeswomen off-hours. I’m not convinced that it’s just an issue for women in nontraditional employment either—standard issue advice to women in any career is to not mix dating life with work life because of the different—and negative—way women who do are perceived (by both male and female coworkers).

You’re focused on some supposed hardship to men who would now have to avoid asking women out on the jobsite the same way they currently have to avoid cigarettes. You have yet to explain how a “don’t ask your coworkers out” rule is any more burdensome than a “don’t smoke on the job” rule.

If you were looking for misuses of “mansplaining,” then “a man objecting to the accuracy of a woman’s summary of how men act to each other” is probably at the top of the list.

I see. So, if I’m working with Joe, Tony and Bill, their description of our workplace interactions can be trusted, but mine can’t. Because “woman”, and women don’t see straight, or hear straight, or interpret interactions correctly. When I say “I want to be treated by Joe, Tony and Bill the same way they treat each other and the rest of their male coworkers”, I mean exactly what I say. If you aren’t willing to take that at face value, at least have the integrity to call me a liar.

I am a man, but I totally get La Lubu and her desire to be left alone.

I work as a teacher, and I have no desire to harass women or act in an unprofessional way. This discussion may be about morality, but I wouldn’t even mind policies or laws against any kind of sexual talk with women on the job. I get it.

My issue is a bit different. I want to do my professional work, and I also don’t want to be bothered. I am older, don’t flirt with any women on the job, and probably appear avuncular. I am also fairly big. So what I get is a lot of requests to do things from women that have no relationship with work. This usually involves lifting heavy objects, moving (or recently: rotating) things like desks, loading things in their car and also fixing things.

I have no desire to do anything but my job and then leave. I usually try to be nice to people and do what they want, but I was in a bad mood with a particularly onerous request, and I just ignored her. This was actually brought up by the principal. I’m not a team player, am I.

I would actually be in favor of a policy or even law that says you do your job and other people just leave you alone. And if you are fired for “not being a team player”, you can sue.

Off to a meeting, this will be short, but

As a single example of why, most everyone understands what “don’t smoke” means and what “smoking” is.

Many people disagree not only about what behavior is appropriate, but also about what “don’t ask your coworkers out” actually means. If it’s restrictive, it won’t produce the effect you want. If it’s broad and retrospectively analyzed, it will be a much greater burden.

[shrug] You’re the one who used the term “mansplaining,” not me. And that carries an implicit claim of expertise-arising-from-gender, because, you know, “man.”

I think that your perceptions of how men interact may be inaccurate, and even if they are, that they may not be generalizable. That inaccuracy may also be true for me, but as a man I have been around a lot of man/man interactions, and of course 100% of my interactions with other men are, personally, in that category. If it comes down to a personal statement of “what it’s like to interact, as a man, with other men” I think I’m usually going to be more accurate, just as I have essentially been deferring to your description of “how women feel” because you’re probably more accurate.

If you choose to view disagreement with your summary as an accusation of lying, I’m sorry to hear that–I actually have a lot of respect for you and don’t mean that at all–but I think that interpretation is coming from you and isn’t my problem to solve.

One of the initial arguments against allowing women into combat, if I remember correctly—and I am remembering discussions from 30 or more years ago, when Selective Service registration was first started by Jimmy Carter—was that the possibility (some argued the inevitability) of romantic relationships, or even just the desire for romantic relationships between those women and the men with whom they were serving, would threaten unit cohesion because it would introduce a kind of competition among the men for the attentions of the (relatively, and probably significantly fewer number of) women; it might give rise to chivalrous feelings among the men towards that woman, potentially compromising their cohesiveness as a unit; it would place anyone who was in a romantic relationship within the unit in a very difficult position if a choice had to be made between the life of their partner and the greater good of the unit (however that might be defined at any given moment).

All of these, it seems to me, are good reasons to have a strict prohibition, and I guess I am assuming one exists (thought obviously I may be wrong) against romantic or sexual relationships within a unit in the military. That they were initially put forward as a reason why women specifically should not be allowed in combat had more to do with very male-centered assumptions about women, about women’s heterosexuality, men’s heterosexuality, the inability of men not to see women as potential sexual/romantic partners and the corresponding inevitability of heterosexual dynamics getting played out, and so on.

The workplaces people are talking about here, obviously, are not the military, but I am struck by how many of the comments I’ve read arguing against La Lubu have as subtext the same kinds of assumptions about men that were used to argue against allowing women into combat.

If it comes down to a personal statement of “what it’s like to interact, as a man, with other men” I think I’m usually going to be more accurate, just as I have essentially been deferring to your description of “how women feel” because you’re probably more accurate.

So to recap: if I describe interactions at work between me and my coworkers, Joe, Tony and Bill, you think you have a more accurate handle on those interactions than I do, despite (a) not being on the jobsite and (b) never having had any kind of interaction with Joe, Tony, or Bill, because you, as a man, have access to their inner world that I don’t have via, what, exactly? Testicle Magic©?

I haven’t been describing anyone’s “feelings”; I’ve been describing behavior. “Feelings” aren’t the issue. I’ve been consistently talking about what is done and what is said, not “what is felt”.

I’ve been told, by co-workers, foremen, and employers, why they feel my, and other women’s, presence on the job is problematic—usually with much apology about how they wish it wasn’t that way, and that women who can do the job as well as men deserve the same chances, but still…..we upset the routine. We create problems by being there. Men waste time trying to flirt, get dates, or impress us. They get possessive of us, or even jealous even when there’s no funny business going on. That we (the women) have the potential to cause problems in the marriages of guys at work, or even break up marriages. That some men are angry that we’re taking up the place of a man; that their son couldn’t get in to the apprenticeship program because of us. That some men have a hard time supporting their family or paying child support because we’re out here taking their place. That they still have a hard time seeing us do the work, even when they know we can do it, because they fear for us. That they struggle reconciling their belief that women deserve the same breaks, the same benefit of the doubt, that men do, with the belief that men are supposed to be better than women at traditionally male activities. That they have a hard time not believing that men—except for the real deadbeats—just are better, just because.

Are you hearing me, gin-and-whiskey? I’ve been told this, candidly, in private, umpteen numbers of times, by oh, more than a hundred but less than two hundred men—which, in the relatively small world in my jurisdiction of central Illinois, is a breathtaking number. Myself, I’ve found it breathtaking that they admitted it, to my face, without any subterfuge on my part to get them to say it. They were just straight up frank, volunteering the information, because they wanted me to understand their perspective, and possibly the perspective of other men who would not volunteer that sort of information.

Read Richard Jeffrey Newman’s response about women in the military. He gets it.

Lalubu: It’s odd because my definition of middle class is basically the same as yours, in that it’s the original, Marxist definition – one based on real economic assets, not cultural cachet or prestige. Those who reliably earn a wage that places them in the top third of the economic pyramid are middle class. There may be some wiggle room around non-wage assets like property ownership, but that’s basically it.

It’s this definition that informs my contention that most women are not middle class*, and that most working class jobs do not feature conferences and networking as a major part of career advancement. Note I say most – I realise your social worker friend is working class and conferences are important for her, but I think she isn’t typical.

When you talk about the white collar working class as a whole you’re including social workers, sure, but you’re also talking about secretaries, helpdesk operators, customer service representatives, payment processors, and mailroom workers. These people aren’t going to any conferences. There are a lot of them.

*nor are most men, but that’s not really relevant to this discussion.

First of all: I regret that what was a pretty productive conversation devolved in the last post. You probably shouldn’t have said I was “mansplaining” and I probably should have let it go when you did, rather than tweak you for it. Pity.

Nope.

If you say “this is what Joe and Tony say they feel” then sure, no reason to disagree. Never met ’em. And if I say “this is what my wife tells me she feels” (she does not take your position) then you have no reason to disagree, for the same reason, right?

But the conversation is about men in general and women in general. So what my wife thinks–or more accurately, what I think that my wife thinks, based on my memory and interpretation of her actions and words–may not be representative of “women generally,” or even “women on average.”

Similarly, what Joe and Tony think–or, more accurately, what you think that they think, based on your memory and interpretation of their actions and words–may not be representative of “men generally,” or even “men on average.”

I don’t dispute that they told you that. But I don’t think they’re necessarily representative of all men, and–especially given the whole “different treatment” stuff which you have discussed–I am not entirely sure how to reconcile that with the current claim that you are granted multiple personal and accurate reports of innermost feelings. Is the different treatment less than you have suggested?

And of course, if you want your anecdotal evidence to be relevant, then I’ll stop having the conversation as if you’re the only source for what women think, and you should be prepared to consider my representation about the thoughts and motivations of the women I know. Deal?

OK, I really don’t get this.

Here’s your next paragraph, emphasis added by me.

Are you using “talking about what is done and what is said, not what is felt” differently than I am, here?

Mythago@99

I’m really not. I’ve been using an example to illustrate a statistical phenomenon I’ve been trying to convey. There’s no either or, but the bell curves also aren’t congruent, which means that in the current reality, women are going to be disadvantaged, because for more men than women it will be harder to deal with their desire in that setting. Couple that with the gender structure of corporate hierarchies, and you get the reality we live in. Do social narratives matter? Of course! No one believes today that it’s fair to harrass a women for wearing a revealing blouse. So, sure, things change. Maybe the extent of arousal is even less now that more women with revealing blouses tend to work and will thus help a certain desensitization. But as long arousal patterns differ in the way they do currently, which means men need to expend effort to be professional, that effort has a cost (if only mentally), and the coroporate hierarchies are male-dominated, women will be disadvantaged.

I’m still not seeing it. You replied to desipis on a point-by-point basis but that paragraph appears to have been left out entirely. Could you repeat your answer?

The “grammar” definition of objectification is the flimsiest of all, and seems mostly to be a fallback when the stricter, more literal interpretation won’t pass muster. There’s a good reason for it too – treating someone as the object to your subject happens in every interaction, from unwanted sexual interactions to unwanted nonsexual interactions to pleasant interactions.

More to the point, every time we are thoughtless or mean to someone in any way, or treat them in a way they don’t want to be treated, you’re doing so without a single care of what they want, and as if their thoughts, feelings, intent, etc. don’t matter. I reject the notion that unwanted sexualization is a special kind of meanness that deserves a special moral (or worse, legal) category. It’s treating others as literally subhuman, while other kinds of group-against-group meanness are bad, too, of course, and I’d… I’d be first to denounce them… but aren’t they just a part of life? No. Or perhaps unwanted sexualization is also just a part of life.

Simply treat others the way they want to be treated, even when it’s hard. The use of terms like this is to imply that others have a greater obligation to do so toward you (or your favored demographic) than you do towards them. Everyone has emotional sore spots, and for some it’s being hit on all the time, but for others it’s other things. Respect others’ the way you would have them respect yours.

It’s my experience that any time someone treats me in a way I’ve made it clear I don’t want to be treated, or a reasonable person could infer that someone doesn’t want to be treated, they aren’t recognizing my humanity.

This argument has a lot of similarity with one that says, “That guy can’t be a misogynist, because he loves his wife.” Yeah, I mean, if you asked me to theorize I’d say it doesn’t make sense, and yet somehow lots of people manage it anyway. (In this particular case, to be blunt, there are lots of people who see other people as warm bodies they can use to get off, no humanity necessary.)

ETA: That’s “lots” as in “many more than I’d expect”, not “lots” as in “a large fraction.”

But the conversation is about men in general and women in general.

No, it isn’t. It’s about changing workplace culture. Changing the idea of what is and is not appropriate in the workplace, as to eliminate existing problems in the workplace, that yes—tend to have a differential impact on women because of pre-existing sexism, but are not exclusive to women. In my more sarcastic moments I might phrase it as “getting rid of the idea that the workplace has to perform as an extension of one’s dysfunctional extended family, most of whom have no sense of boundaries”….but hey, not everybody’s family is like that.

Are you using “talking about what is done and what is said, not what is felt” differently than I am, here?

Yes. All that falls under “what is said”—I didn’t guess about it; those were personal admissions. I get it—-you’re an attorney, so you’re trained to assume that when people make admissions as to their thoughts or feelings, they are lying or otherwise misrepresenting themselves. In the absence of any credible evidence to the contrary, I take personal admissions at face value, while being mindful that a person’s thoughts and feelings are exemplified by their behavior (i.e.: what they do trumps what they say).

What those various statements over the years boiled down to is: there is a tension between values. The values of fairness and equality against the messages of what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman. That’s a very human problem—living our values in the face of the various “isms” (i.e.: reductive beliefs about certain segments of humanity). That’s why I didn’t get angry with them, or in turn reduce my assessment of them to “sexist asshole male chauvinist jfsdkldffx#!!”, and my acceptance of those statements at face value, without further action on my part, is probably why I heard so many of them over the years.

At the risk of repeating myself, none of this is happening in a vacuum.

New York Times link

It’s like Amp’s cartoon was right on the money or something… ;)

Harlequin@107:

Except we’re not disagreeing about “sexual harassment”, at least as its typically defined. We’re disagreeing about the incidental, non-repetitive, requests for a date. We’re disagreeing because I don’t see that as something that significantly detrimentally affects many many people in many different industries. I’m not sure we can resolve this disagreement with anecdotes.

What’s more I think you are underestimating the extent to which things-that-aren’t-sexual are commonly problematic. One example I didn’t include before is height. In terms of direct workplace discrimination, height plays a greater role in predicting salaries than gender. Height discrimination is significant enough it may even explain a significant portion of any gender wage gap given the difference in average height of men and women. Yet, I hear people who are concerned about social justice constantly going on about the gender wage gap, and nary a peep about height discrimination in comparision.

Yes, that is what I meant: men and women in general in the workplace. Should have been more clear.

Yes, absolutely. You cannot satisfy all values at the same time.

See, this may be part of the root of our disagreement, because IMO generally fairness and equality are competing values. Fairness is outcome based: it’s “fair” for someone to get more help from the law if they are worse off to begin with. Equality is process based: a law which treats classes differently (or which is designed to come down more harshly on a particular class) is not equal.

[Wow. A large northern flicker just landed on the suet outside my window, about three feet from my head. It’s munching away. Big woodpeckers are awesome. Just had to share.]

Even if you get past equality/fairness it’s a conflict. At work–as with everywhere else–the “right to exist without being bothered” and the “right to act freely” are inherent conflicts. Either someone has to shut up, or someone has to suck it up. Obviously the employer can impose arbitrary rules (which is why I’m arguing against the idea of additional rules, not the right to implement them) but that conflict is ongoing.

So as with so many things, the outcome depends on what you assume needs to be protected. If you want to have people freer at the workplace so long as their behavior isn’t objectively inappropriate. Or if you want individual employees to have more say in who says what and when. And so on.***

At the risk of repeating myself as well, I don’t claim that it is, was, or will be. I mean, let’s face it: lots of our disagreement is probably about methods to reach mutual goals; some of it is about theory; some about language choice; and some about motivations. But if you asked both of us “this is specifically what happened here, what should the outcome be” I suspect we would probably agree on 90% of outcomes. We’re arguing margins.

[ok, I am not making this up. the flicker left. but now there’s a redbellied (which actually has a bright red head, not a red belly) in his place. i love my suet.]

After this I actually have to drop out for a while because, wouldn’t you know, I need to go file some wage cases :)

*** An interesting side note: To the best of my recollection, many people here generally argue for increased employee rights, and against harsher employer rules. I might sum up that position as “so long as it’s not outside social mores then as a rule your employer should try to stay out of it.”

(I’ve taken the position that it’s OK if employers choose to make harsher rules, if they think they relate to employment, though I never claim that they should make them.)

But the behavior we’re discussing here is not socially horrible. (More accurately, nobody is disagreeing that horrible behavior should be deterred. We’re disagreeing about things which are OK outside of work)

How do folks reconcile that? It can’t be “general discomfort” because you don’t want black folks getting fired for discussing Ferguson at work. It can’t be “issues relating to sex” because you don’t want folks getting smacked for reading amptoons. It can’t even be “it has to do with work” because heck, isn’t it the employer’s job to figure out whether something is worth banning, or not.

Do you think this is a special exception? Or do you think this fits within your existing rule?

desipis: Yes, height discrimination in pay is common (as is weight discrimination from your first set of examples, and favoritism of good-looking people, and many other things). But is it more commonly acted out through short jokes, or through subconscious pay discrimination? My experience has been the latter, although my knowledge comes from being around shorter colleagues, not from first-hand experience, so I’m open to being proved wrong. In other words, the discrimination is common, but it doesn’t come with a side order of common employee interactions supporting the discrimination. Where those interactions exist, sure, put some measures in place to help prevent them. “Not letting people get harassed at work” is a fine reason for employee rules, as far as I’m concerned. (I do also support making distinctions on whether something’s actually harassing, of course–and that is also a source of disagreement between us in this case.)

***

g&w:

Well, a few things:

– I don’t view this as “employer vs employee” so much as “employee vs employee, with the employer intervening on one side.” This isn’t a thing where employers are covering their asses w/r/t lawsuits and none of the employees want it, it’s a thing where female employees are suggesting this rule. (This also applies to the “employers figure out what to ban” point you made: unless you expect employers to be psychic, it may be that employees have to point out things that are making their work less productive. Saying “the employer hasn’t noticed it” is not the same as saying “it doesn’t occur.”)

– As to your “general discomfort” example, is it a surprise to you that social justice types (or…anyone) would support different rules for different situations depending on who’s being most heavily impacted and what kind of activity is being prohibited? Saying “you wouldn’t support a rule that suppresses political expressions by black people that makes white people uncomfortable, so why would you support a rule that suppresses certain social overtures by men that make women uncomfortable” is comparing two different kinds of speech or action (which should be an important distinction to anybody), and comparing one made by a group not in power to one made by a group in power (which you know social justice types commonly distinguish).

Also,

I mean, it can’t be a surprise to you that there are behaviors which are fine outside of work and not-fine during work. We’re making the case why it’s not-fine specifically during work hours, so pointing out that it’s fine outside work hours isn’t a counterargument.

***

This isn’t strictly relevant, because it’s employee-customer relations and not employee-employee relations, but I had a sudden memory of two female friends in college who worked in customer-service-heavy jobs (cashier and hotel desk clerk) who bought cheap rings and wore them as if they were engagement rings, because they got hit on so much by customers and that reduced it.

Thx. I didn’t ask because I think it’s some sort of inconsistency “zinger”, but because I was simply curious which path you’d use to reconcile it.

That wasn’t a counterargument. All I was doing is to try to head off the potential misreadings that I was, I dunno, suggesting that I was generally opposed to any regulations at all, anywhere.

Clearly, on reread, this was not one of my more well written posts. (Or should I say “not clearly…?”)

This, though:

Eh. I’m not so sure that generally encouraging employers to treat people distinctly differently based on group characteristics is a good idea. I think it’s a disservice to the claimed goals of SJ. But then again, I am more of a “look to a general rule first, and examine claims to exceptions carefully” kind of person, and a lot of SJ is basically exceptionalist at heart. No real surprise that we disagree.

Fair enough. But since the exact level of…problematicity? ugh, is there a word for that?…of workplace requests for dates is one of the things that we’ve been discussing, I didn’t want to let it fly past when you seemed to assume your side as one of your points. :)

No one is saying “heterosexual men can’t ask women out in the workplace but everyone else is fine,” or even “nobody can ask out women at work, but people of other genders are fine.” This is a blanket ban. So it’s not treating people differently based on group characteristics. Now, I see you could make a claim for it being unequal based on your statement above that something’s not equal if it’s “designed to come down more harshly on a particular class”, which I broadly agree with, I guess–voter ID laws being an oft-discussed example here of something that’s unequal based on that clause–but in this case, where you’re trying to prevent a sometimes-problematic behavior that is practiced mainly by one class, I don’t think you could design a solution to that problem that didn’t also come down more harshly on that class than on others. You’re left with solutions of varying levels of inequality, or not fixing the problem at all. (Or you may not agree that it’s a problem, period–as some here have been arguing–but that’s a separate thread of the argument.)

Harlequin:

Problematicotudinosity.

Grace

Harlequin:

I think it’s more than just a matter of varying levels of inquality. I mean consider the issue about how the standard of professional dress are different for men and women. One could argue that the prevailing standards place an unequal burden on women in terms of extra effort or it being impossible to please everyone with their choices.

So let’s say someone proposes that everyone simply be mandated to wear burlap sacks to work and that jewlery and makeup be banned. Probem solved. People don’t need to wear fancy or comfortable clothing when they’re working. They can wear clothes that express themselves or relax in comfortable clothing during non-work hours. With this rule everyone will be treated equally.

Yet, even though there’s no inequality, it still seems somewhat like punishment to take away the freedom of people to dress they way they want within the practical and business driven limits of the workplace. Given that many people haven’t treated others unfairly because of dress standards, this punishment seems harsh and unfair, even though it might be equal.

Grace: Beautiful, thanks! I knew I could trust in your wisdom. :)

desipis: I’m afraid I have to ask you to come up with another example, because I’ve been turning your comment over in my head, and I just can’t get past the fact that you just described a (particularly itchy) uniform as if it were a punitive assault on personal freedom. Like, that is not a hypothetical example (except for the burlap). It’s a relatively common feature of both workplaces and schools, not to mention the criminal justice system.

The burlap, I admit, is probably a bit harsh.

On a more general note, the reason I called this measure unequal in my comment to g&w was because, although the end state is the same for everyone, the difference between the pre- and post-no-dating-requests-rule states is much larger for men than women, broadly speaking. Possible solutions may also be harsh, which I think is something you were trying to get at with your comment–I don’t think this one is, but it’s one of the things we’re discussing here, so for the sake of argument–but I don’t think you can design a solution which is equal for this particular problem, regardless of how harsh or kind the solution is.

Harlequin: Ok, let’s take the staff lunch-room kitchen. From my experience these aren’t full kitchens, but usually have fridges, kettles, microwaves, sandwich toasters, etc. It is also usually left to the staff to keep it clean between themselves. Let’s say at a particular workplace the men and the women have different standards (on average) about the use of the kitchen. The men are happy to let things slide and the women want a clean and orderly kitchen. This of course leads to the women doing significantly more of the cleaning than the men. This obviously leads to disputes about how the cleaning burden falls unfairly on the women.

The solution? No kitchen for anyone. No fridges, no kettles, etc. Inequality removed, problem solved. But isn’t this an overly harsh rule despite the fact it achieves equality?

No one is saying “heterosexual men can’t ask women out in the workplace but everyone else is fine,” or even “nobody can ask out women at work, but people of other genders are fine.” This is a blanket ban. So it’s not treating people differently based on group characteristics.

Yes, this. Thank you, Harlequin. If there were a workplace rule prohibiting insults based on weight (which is outside of existing sexual harassment and civil rights laws), such that both fat and thin people were expected to not insult anyone else at work with “fatso!” or “toothpick!”—fat workers would receive the most positive impact from the policy not because of disparate rules or disparate enforcement, but because fat people are more stigmatized in this society and thus more likely to receive insults to begin with (including from other fat people).

desipis, setting aside the problems with your gendering of workplace sloppiness, sloppy kitchens aren’t an aesthetic problem—grease, crumbs, dirty dishes/utensils, and trash that isn’t thrown away in the wastebasket attracts cockroaches and rodents rather quickly. Even if the kitchen isn’t officially shut down, sloppy workers end up de facto shutting the kitchen down for everyone else because no one else wants to deal with the resulting conditions—they’ll either go out to eat, or bring a cold sandwich/hot thermos, or a deskside mini-microwave.

Understand—I’m not motivated by “revenge” or “punishment”. My goal is simply to be treated with the same level of professionalism that my male coworkers are, and requests for dates on the job are a barrier to my employers and coworkers (even clients, if they visit the jobsite or it’s a remodel) seeing me as a professional. I want to change workplace culture, so that asking for dates on the job is generally regarded as unprofessional behavior, not “bad” behavior—appropriate for outside the workplace, but not inside the workplace, and is why I liken it to smoking. Smoking on the job is generally recognized (even by smokers) as not appropriate to the workplace.

You’re seeing this as “employers against employees” or “one set of employees against another set of employees”. I’m seeing it as “appropriate workplace behavior vs. inappropriate workplace behavior”. Go look at some magazines or websites geared towards working women. You’ll notice a plethora of articles focusing on how women can change their appearance and behavior in order to be regarded as professional—that it takes more than just credentials, experience, and ability in order for women to receive the same chances as men. Notice how much of the advice geared towards women heavily moderating and managing their (our) workplace image (which we have to do to a greater extent than men) is in response to men’s behavior. Note also that much of the advice takes pains to gender this image management, so that the women seeking to take this advice don’t go overboard in reducing “feminine” signaling, because to be seen as too-masculine or too-gender-neutral is also a problem.

The solution? No kitchen for anyone.

Or one of a number of any other solutions, like assigned tasks (“Bob is going to handle coffee-making on Mondays”), including break-room cleaning as part of what the cleaning service does, or even just everybody sitting down and talking it over.

Also, you do realize that many workplaces in fact require uniforms, to the point of issuing uniforms? If you’ve never worked in a blue-collar or service job I guess you wouldn’t know that.

It’s fascinating how arguments about treating women with equal professionalism in the workplace always devolves into how doing so would make the workplace a gloomy, rigid, no-fun dystopia for everyone.

desipis:

I have to confess that, for me, the analogies you keep coming up are growing increasingly absurd. Asking someone out on a date—regardless of the genders of the people involved—is qualitatively different from height, weight, sloppiness in the kitchen, or dress-code requirements, not matter how much real and/or potential discrimination you can find in those other situations.

The fact is that asking someone on a date leaves both people vulnerable, emotionally and psychologically (and socially, culturally and politically) in ways that none of those other situations do; and that kind of personal vulnerability can be very disruptive in the workplace, not to mention potentially damaging for the people involved. I don’t mean that people might not feel vulnerable about their weight or height or whatever; nor do I mean that discrimination regarding those things is necessarily trivial. But none of them involve initiating and/or rejecting and/or managing a romantic/sexual relationship (along with all the corresponding social and cultural baggage) that is, by its very nature, not part of the work that needs to be done and also not necessary for the smooth functioning of the workplace—the way you might argue that keeping the kitchen clean, for example, contributes to a positive work atmosphere, or that uniforms help promote a company’s image and brand.

Not to recognize this difference, it seems to me, is willfully to ignore a great deal of what is really at stake in the points La Lubu is trying to make.

“It’s fascinating how arguments about treating women with equal professionalism in the workplace always devolves into how doing so would make the workplace a gloomy, rigid, no-fun dystopia for everyone.” — mythago

Remember, ladies, if you want to be free to do your work without being propositioned, it’s equivalent to shutting down free speech in America and simultaneously opening yourself up for previously male-only

hazingbonding rituals. Ladies, why do you hate freedom? Fun? Equality?The cartoon was great. The discussion has some real manipulative derailers.

Exactly kt. The whole point was that sexual creeping and rape cost women career opportunities. And look, here’s another example: young journalist interviews older male author, author creeps on her and de-rails the whole interview, journalist spends time referencing her boyfriend and evading creeping rather than getting good material for her article, interview never gets published. Oh, and who knows what assignments she turned down in the future because she didn’t want to go through that again? Or what assignments her editor didn’t give her because she “flubbed” this one?

Sure. I’ll go even farther: it would be nice to treat every person in a manner that each considers to be professionalism in the workplace. Doing so would not automatically make the workplace a gloomy, rigid, no-fun dystopia for everyone.

Simple agreement!

But when we’re done shaking hands in the motte, it’s time to recognize the real argument.

People don’t do that right now. And in all likelihood they won’t do it any time soon, unless they are coerced: change is slow. And making matters worse, people do not even agree all that much on what “professionalism” is. Nor, in many cases, do they agree on how it should be “equalized” (from the perspective of the actor, or the actee?) or what the appropriate procedure is for resolving a dispute when two people, unsurprisingly, disagree on whether something was “professional” and/or “equal.”

So the real question isn’t “should women be treated with equal professionalism in the workplace?” It’s actually more like this:

Folks would like to figure out a way to coerce people to act “professional,” whatever that means to each of them. How should we attempt to define or redefine “professional” behavior, in the context of a new set of rules that are designed to punish behavior which will be deemed “unprofessional?” Similarly, to the extent we will require that people are treated equally, how should we attempt to define “equal?”* And who is making the judgments about whether or not something fits the definitions?

Unlike the first one, the real question is complex as hell. Whether or not someone comes to a different conclusion in the end, if it seems “simple” or “obvious” or anything similar, I have difficulty understanding how.

I just listened to This American Life about “T” as in testosterone, and in act 2 they’re interviewing a transman who was a butch lesbian before about the difference it made for him. This seems relevant to this conversation, too.

http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/220/transcript

Quote:

Frankly, I don’t see how. Again: this proposal (lack of propositions/dating requests at work) has to do with behavior, not instinctual or unexpressed emotions. When something is biologically harder for some people than others, then yes, we should take that into account in designing rules/policies/whatever. But it’s not a get out of jail free card when weighed against the interests of other people. And you still haven’t established that “is likely to think about having sex with someone” necessarily precludes “is able to work with them like they work with people they’re not attracted to” in some hardwired way (as opposed to being the result of reduced pressure to have self-control in this area).

Not to mention that “person notices difference when their hormone level changes” does not imply “the way they feel after that sudden increase in hormones is the way people with that hormone level naturally feel all the time.” Note that the interviewee is talking in the past tense: he’s describing what happened when he started testosterone, and explicitly mentions he feels he understands adolescent boys better now. So he’s really talking about what male puberty is like, and not male adulthood.

I could also take your argument to an absurdist level: he also describes being turned on by the warm, vibrating Xerox machine. Should we allow male secretaries to be excused from making copies?

I have been working on a poem for my next book that deals with a particularly sleazy example of the dynamic illustrated in the cartoon. This was many years ago. A woman friend of mine, also a poet, who survived the kind of brutal rape and sexual assault that you usually associate with TV shows like Criminal Minds or Law and Order: SVU, had finally found a language in which to write poems about her experience. When she had enough material that felt ready for an audience, and when she felt strong enough to read them aloud, she sent samples of the work to a local poetry impresario—and I choose that word on purpose. He was, maybe still is, a true big shot on the local scene, someone whose “seal of approval,” so to speak, really meant a lot.

He read her work and was apparently impressed because he gave her a featured reading. Twenty minutes on stage to read her work. She did. It went very well, and they all went to a bar afterwards. At some point, he sidled up to her—her husband was in ear shot—and told her, “You know, when I finished reading your poems, I was hard all night.” Now, just to be clear, while these poems—some of which she shared with me—are explicit, none of them are sexy-erotic; they are about sexual violence, sexual violence that she, the writer, experienced, and they are about critiquing precisely the jaw-dropping and presumptuous arrogance contained in his comment.

People get turned on by whatever turns them on, and so my point here isn’t to judge him for having been aroused by the poems, but that he shared this with her, in the way he did….

I do not know for sure because she and I lost touch for a long time, but my guess is that this incident contributed to the fact that she stopped writing altogether and is only now, after eight or nine years, is she contemplating the possibility of starting to write again. And how is she going to make the decision about where to submit work if she ever decides that she’s ready to start giving public readings again?

it’s time to recognize the real argument.

The “real argument”? Do you mean the one that is honest enough to admit that there is already a great deal of consensus as to what constitutes professional behavior? The one that is honest enough to admit that the objections you raise are the exact same objections raised in the past to sexual harassment laws and policies? (“you say it’s “sexual harassment”, but how do we really know what sexual harassment is? I know some women who regard what you call “sexual harassment” to be a compliment, or a cheerful way to lighten up the workday!”)

This, too, seems relevant to the conversation:

The idea of two sexes is simplistic.

The one I mean is the one I said, though of course that’s a summary.

Earlier in one of our less-polite interchanges, you started getting into the “are you calling me a liar?” stuff. Are you really going to do that here, to me?

How many times do we need to dance around the same frustrating argument, which you keep phrasing as if there’s some obvious thing I’m NOT agreeing with?

I already said “But if you asked both of us “this is specifically what happened here, what should the outcome be” I suspect we would probably agree on 90% of outcomes” so it’s not as if there’s some “gotcha” moment going on–much less a dishonest one.

There are plenty of things where you can draw a line around them and get consensus that they are “professional behavior,” especially if you provide missing context like “…in a law firm” or “in a commercial kitchen.” But so what? That’s as non-useful as noting that “there are a lot of acts which are universally accepted as rape,” as evidence that we have a lot of disagreement about how to punish OTHER acts.

The things which have major consensus as “nonprofessional” are not, by and large, what we’re talking about: mostly because they are already illegal. And since nobody is arguing against it, and since various folks including me would happily support better enforcement of existing rules (did you see the “new rules” part above?)

So fucking what?

Yes: some of the arguments are similar to arguments that were made in different, worse, circumstances. Just as some of the rules are also similar to other bad things, because there are lots of instances of folks using rules badly. this whole analogy is basically pointless: the fact that someone made an argument in bad circumstances says nothing about it now.

Practically speaking, you need to define the harm in order to provide a right and a remedy. You don’t seem to understand that, and as a result you incorrectly mock the attempts to define it.

If you want a more familiar analogy, replace “sexual harassment” with some traditionally over-vague law, perhaps one which is often selectively overenforced against POC. Maybe “loitering,” or “threatening behavior,” or “acting suspicious,” or–wait for it–“harassment.” I strongly suspect that in more traditional liberal areas, you’d acknowledge risks of inaccuracy, discretion, enforcement, overbreadth, and the like. I don’t understand why you seem to refuse to acknowledge that analysis here.

Nobody involved should assume that their own interests are accurate representations of everyone in the group. And nobody involved should assume that their own preferences are more important than everyone else.

I don’t think sexual harassment is a compliment, of course. But since we’re talking about something with no objective definition, I treat desired definitions as a preference, not natural law. So if there were a large enough pool of people who did not share your perspective, I’d try to consider their interests as well, whether or not you lobbied for them to be ignored.

Also, I am attempting (however unsuccessfully) to at least consider both sides’ interests, and have made a variety of concessions based on your representations of what “your side” wants. It doesn’t seem to me that you are doing much to consider both sides/ interests; and it doesn’t seem that you are willing to make many concessions on your part: although that fits into the above-quoted theme of mocking those who take a different perspective, it’s a bad perspective to use to make new rules.

Harlequin,

No, agreed, the weighing is what’s important. My general point, as per my initial comment to the op, is still that it is *this* difference coupled with corporate structures rather than rape as such that makes professional success harder to achieve for women. I also suggest that we, in order to consider ourselves able to address that discrimination, have come to a point where we – as in “the general progressive political discourse” – disregard basic endocrinological differences between sexes and genders because they seem inconvenient from a fairness point of view. And that’s not how fairness works. I don’t have a lot of answers to the conundrum, but neither have those who claim they do.

@SomeOne, what exactly is “this difference”? Earlier you were arguing that there is a social component and desensitization (i.e. more women in the workplace) is probably helping; now you’re claiming there is a “basic endocriological difference”. Your evidence for the latter is… a single transman who, immediately after beginning hormone therapy, went through a period where he found everything arousing, up to and including an operating Xerox machine.

This is not about inconvenience or wanting the world to be a fair place. It’s about your pushing a narrative – men can’t help their boners, women can’t understand that because their ladyparts crave romance – that is not only insulting to men and women, but is laughably unsupported by anything you’ve shown so far, which I guess is why you keep backing off and throwing out qualifiers.

@Mythago,

I don’t see how that is incompatible. There *is* a social component, including desensitization, but there is also a biological/endrocrinological difference that is usually denied in such discussions merely because it’s ideologically inconvenient. I’m also not denying that men are used to (and require) higher concentrations of testosterone, and that one transman is unlikely to be the entire scientific story, albeit it is an interesting one, and possibly one that social-blank-sheeters and feminists can easier relate to than accounts of cis-men.

So far, nothing has convinced me that rape/fear of rape/rape culture, rather than a general difference in male and female sexual responses coupled with corporate structures, is the main reason for the disadvantages women experience in their professional lives.

That’s an unfair over-simplification of what I suggested.

but there is also a biological/endrocrinological difference that is usually denied in such discussions

Well, we’re having a discussion right now, so it’s not really necessary to talk about imaginary other discussions. Can we dispense with the evasive passive voice, please? Where is your evidence of “biological/endocrinological” difference that is responsible for the disparate treatment discussed in Amp’s cartoon, and elsewhere in this thread, particularly by La Lubu?

SomeOne:

You’re missing the point: The corporate structures that exploit those differences—or that allow those differences to be exploited—such that women experience “disadvantages in their professional lives” are themselves part of rape culture, by which I do not mean, simply, a culture that normalizes those differences in ways that result in (sexualized and other) disadvantages for women.

You keep arguing for an explanation that is rooted in nature/what is natural, as if our perception/understanding of what is natural somehow lies outside our other, gendered, socialized, sexualized perceptions of the world.

If I understand what I’m reading correctly, this is an argument between the position that biology is destiny and the position that biology is not destiny as represented by Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus vs. No they’re not.

Do I have this right?

Jake Squid, I don’t even know any more what’s happening in this thread, but that description of it made me laugh out loud! :)

@Mythago

http://io9.com/5977668/do-men-really-have-higher-sex-drives-than-women

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.186.5369&rep=rep1&type=pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8532819 -> “The administration of androgens to females was clearly associated with an increase in aggression proneness, sexual arousability and spatial ability performance. In contrast, it had a deteriorating effect on verbal fluency tasks. The effects of cross-sex hormones were just as pronounced in the male-to-female group upon androgen deprivation: anger and aggression proneness, sexual arousability and spatial ability decreased, whereas verbal fluency improved.”

etc.

@Richard,

No, I’m saying that “we” have a tendency to ignore the “nature” aspect in the complex interaction between nature and nurture, because, from an activist point of view, it’s far more convenient to assume that only nurture matters. So, basically, I’m arguing that nature lies *within* our gendered, socialized and sexualized perceptions of the world. And disregarding it won’t work.

@JakeSquid,

No, you don’t. Biology is disposition, not destiny.

SomeOne:

If that’s the argument you’re trying to make, it seems to me that you’re not doing a very good job of it. At the very least, the way you are separating rape culture from “natural” male and female sexual responses and how those are deployed/experienced within corporate structures seems to me an artificial one at best.

Wait, are you arguing that because some people’s biology supposedly makes it harder for them to resist acting on sexual urges, they shouldn’t be blamed when they do so?

Or are you arguing that because some people have such a hard time resisting acting on sexual urges (due to biology), they should be excluded from polite society and the world of work in order to make sure that other people aren’t economically and socially disadvantaged as a result? Because if you are, wow, that’s radical.

@Elusis,

I’m saying we need to strike a balance that doesn’t ignore what I consider to be reality (I accept that others disagree with that assessment). People (men, usually) have always been excluded from polite society when they have not been able to live up to the required social standards. So, no, people should not be excused when it’s harder for them not to act on their urges. But there should be some sort of understanding that it *is* harder and social attempts to address the issue should not ignore the issue because it is more convenient.

Personally, ideally, for me, that woudl amount to a climate where all people can talk about these matters without fear of harrassment or accusation. To gain a better understanding of what the other’s experience is like. Sadly, I don’t think that’s a very practical approach in most instances, and I’m not sure how to address this in a less conflicting way.

OK, so that’s interesting and all, but what about addressing the actual problem shown in this comic, that of the disproportionate economic and career impact of rape culture on women? Or do you just want to talk about what you want to talk about, which is apparently how hard you feel it is to be a person whose biology is particularly influenced by testosterone when there are objects of your potential sexual attention around?

I mean, if you genuinely feel that you cannot control your testosterone-influenced behaviors around others, I would invite you to present yourself to the nearest police station and ask to be taken into protective custody. Or when you say “a climate where all people can talk about these matters without fear of harassment or accusation,” are you mostly saying “I wish I could talk about my boner without people telling me it’s inappropriate”? Because: Unless you’re talking to your sexual partner(s), your therapist, your support group, or your doctor, it’s pretty likely that it’s inappropriate. And if you find THAT difficult to manage, see beginning of paragraph.

@Elusis,

thanks for illustrating the problem I referred to.

Way to go personal instead of addressing the structural issue raised.

You’re not addressing “the structural issue raised.” You’re persistently trying to change the subject to what you want to talk about, and wrapping your interest in a very thinly veiled self-reference. (Because you are totally resistant to any argument or evidence to the contrary of your assertion about the biological differences between binary genders, you come off as someone extremely mired in your own myopic view of the world.) And then you declare yourself (or your self-insert) the victim when people say “um, seriously? YUCK.”

Again, I ask: what about addressing the actual problem shown in this comic, that of the disproportionate economic and career impact of rape culture on women?

Apparently that’s not of interest. This is my surprised face.

Late to the party, but I completely 100% agree with what La Lubu, mythago and others are saying. All workplaces should have a no dating/sexual interactions/propositioning during work hours policy. I’ve been hit on/asked out/propositioned while trying to work, and it makes things really uncomfortable for me AND my uninvolved colleagues who are present at the time (no matter how politely worded, or how graciously the “no” was accepted).

I do not understand the biological argument about this at all. Biology certainly does drive sexual attraction, but most people learn self-control by the time they reach working age. I mean, people also experience a strong biological urge to urinate when their bladders are full, but I have never seen anyone in the workplace start peeing on the floor, call attention to their biological urge to urinate, or make a big production about having to quietly leave the room to take care of their personal needs. While it may be possible that some people experience sexual attraction at the workplace as powerful as the need to empty a really full bladder, if it is possible to control one strong biological urge, it is certainly possible to control another. It is just that some men are not used to having to put the brakes on when it comes to their sexuality.

I know plenty of people who have met their partners at school or work. Most of them are extremely careful to keep the personal separate from the professional. I have experienced loss of opportunity through the specter of sexual violence as depicted in this cartoon (fortunately not as severely as leading to rape). I am fortunate that it is far more common to have to worry about unwanted advances (even those that g&w would not consider harassment) than to worry about sexual violence in my career. That said, since I am in a male dominated field, I do experience unwanted advances pretty much every time I travel for work (even wearing a ring), which puts a damper in my enthusiasm for travel, and almost certainly affects me subconsciously. If everyone followed (or was expected to follow) a “no hitting on people while doing work” rule, it would make many people’s professional life a lot better without seriously constraining anyone else.

In summary: Like a colleague? wait until after work (and this including work-related networking!) to approach him or her. He or she will probably appreciate you separating the professional from the personal.

Jane Doh @161: the ‘biological argument’ is used because there’s not really a good alternative to it. (We are a little past the era where there’s anything like wide acceptance of the belief that women only enter the workforce to tempt men.) It’s a lot like the way that certain creationists peddle intelligent design; it’s not so much that they care about the science as that they understand saying “but it’s God’s truth” is not going to be convincing for people who don’t share their underlying philosophy.

I don’t think that SomeOne is trying to be deliberately dishonest. I do believe SomeOne has a core belief that men and women are just different (and largely opposite), and that the various links they have thrown out are not so much a foundation of that position as an after-the-fact justification meant to convince the skeptics.