Probably no piece of medical advice is so frequently given, and with so little rational basis, as the pressure on fat people to lose weight.

1. For The Vast Majority Of Fat People, Weight Loss Dieting Doesn’t Work

When I say a weight loss diet (or “diet,” as I’ll refer to WLDs for the rest of this post) doesn’t work, I mean two things. First of all, I mean that for most, the amount of weight lost isn’t enough to turn a fat person into a non-fat person. Second of all, I mean that for most, the weight loss cannot be sustained over the long term (say, five years).

Here’s a remarkable fact: There isn’t a single peer-reviewed controlled clinical study of any weight-loss diet that shows success in losing a significant amount of weight over the long term. Not one.

Isn’t that amazing? It’s not as if Weight Watchers, Slim-Fast, diet clinics, Jenny Craig, and the thousands of other companies making billions of dollars from promises of weight loss haven’t been trying. If anyone could reliably make fat people thin, they’d soon have more money than Microsoft and Haliburton combined.

From a review of empirical tests of weight-loss plans by Wayne Miller, an exercise science specialist at George Washington University:

No commercial program, clinical program, or research model has been able to demonstrate significant long-term weight loss for more than a small fraction of the participants. Given the potential dangers of weight cycling and repeated failure, it is unscientific and unethical to support the continued use of dieting as an intervention for obesity.

Let’s closely examine a study cited as proof that weight loss diets work (I examined this study in a previous post): “Behavioural correlates of successful weight reduction over 3y,” from The International Journal of Obesity (2004, volume 28, pages 334-335).

First of all, let’s notice that the definition of “successful weight reduction” is extremely forgiving: According to the study, “weight loss of 5% or more from baseline to 3 y FU [three year follow up] was defined as successful weight reduction.”

So if a 400 pound man becomes a 380 pound man over the course of three years, according to this study that is “success.” But there isn’t any evidence that a 400 pound man who loses 20 pounds will be any healthier, or have a longer life expectancy, than a 400 pound man who maintains a steady weight. (In fact, as we’ll see, the opposite is true – the 400 pound man who never lost weight will probably live longer). Nor is there any evidence that it’s healthier to be 190 pounds than 200 pounds.

And keep in mind, the amount of weight loss drops steeply over time – so when a study like this defines “success” as weight loss at three years, the effect is to unrealistically exaggerate the success of the diet plan being studied. If “success” was described as taking the weight off and keeping it off for a lifetime, the success rate of these studies would be barely above nonexistent.

Still, three years is relatively good methodology – many diet studies measure patients at 3 or 6 months and that’s all. Unfortunately, this study’s methodology is terrible in another way: the 77% drop-out rate. This means that the researchers have no idea how many people followed their instructions, found that they weren’t losing weight, and so quite reasonably dropped out.

So – of the 23% of subjects who didn’t drop out altogether – how many actually succeeded in maintaining a 5% weight loss over the course of three years? 48%. Put another way, of the 23% minority who stuck with this study’s plan, most weren’t able to lose even 5% of their weight over three years.

But what about the most successful group of dieters – those who managed to obey the seven separate diet restrictions this study called for, for all three years? (That’s a grand total of 198 dieters out of the initial group of 6,857, or 2.8%). Of this tiny, select group, 40% failed to meet this study’s extremely forgiving standard of “successful weight loss.”

Now, the above study is one that weight-loss advocates themselves cite as proof that weight loss is practical and possible. Is there anything there to convince a 300 pound person that becoming thin is a practical and likely effect of weight-loss dieting?

One possible factor making it difficult to lose weight permanently is that our bodies may adjust to situations of reduced food intake by lowering metabolic rate and increasing the proportion of food stored on the body as fat. (Some studies support the existence of this effect, but it’s not proven beyond all doubt.) The evolutionary benefit of this is obvious; humans who lower their metabolic rate and store more fat in conditions of famine are more likely to survive and reproduce. But as a result, the more you diet, the harder losing weight becomes over the long term, and the harder your body will fight to retain fat.

2. Losing Weight Makes It More Likely You’ll Die Sooner

Most of the time, people on weight loss diets gain back the weight they lose. But that doesn’t mean they’re back where they started, healthwise. Many studies have found that losing weight – even if the weight is regained – is associated with higher mortality rates. From David Garner’s and Susan Wooley’s review article “Confronting the Failure of Behavior and Dietary Treatments for Obesity”:

There are few studies in the medical literature that indicate that mortality risk is actually reduced by weight loss, and there are some that suggest that weight loss increases the risk of death. In an American Cancer Society prospective survey of over 1 million people, individuals indicating that they had lost weight in the past 5 years were more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than those whose weight was stable. In a 10 year follow-up of men who were asked their weight at age 25, Rhoads and Kagen reported that heavy respondents who had later lost weight had almost twice as high a death rate as those who maintained a high but stable weight. Moreover, those with a high but stable weight had the same or lower death rate as thinner men. […] Although weight change was unrelated to mortality for women in the Wilkosky et al. study, the odds ratio… for men indicated that each 10% loss of weight was associated with a 14% increase in all-causes mortality and a 27% increase in cancer mortality.

Finally, in a study of mortality risks among 16,936 Harvard alumni, Paffenbager at al. not only found that the highest mortality occurred in those with the lowest body mass index (below 32), but also that those who had gained weight since college had a significantly lower mortality risk compared to those who had minimal weight gain since college. According to the authors, “alumni with the lowest net gain since college had a 29% higher risk of death than their classmates that had gained the most.” Thus, even if one accepted the premise that obesity is a dangerous condition and weight reduction a realistic goal, it is an unproven hypothesis that weight reduction actually translates into increased longevity.

When you read that, you probably had the same reaction I first did, which is to wonder if the higher death rates associated with weight loss might be caused by unintentional weight loss among already sick people. Glenn Gaesser’s book reviews several studies that distinguished between unintentional and intentional weight loss. One study found that for overweight women with pre-existing health conditions (such as high blood pressure), even a very small weight loss – just a couple of pounds – decreased mortality. (There was no increased benefit in losing 20 or 30 pounds instead of just 2 or 3). A similar effect existed for diabetic men. For virtually all other groups, however, intentional weight loss either had no effect or led to increased mortality.

Among the two-thirds of the study participants who were healthy to begin with, intentional weight loss was anything but good. For example, compared with healthy, overweight women who remained weight stable, women who intentionally lost between one and nineteen pounds over a period of a year or more had premature death ates from cancer, cardiovascular disease, and all causes that were increased by as much as 40 to 70 percent. Unintentional weight gain, on the other hand, had no adverse effects on premature death rates for these nonsmoking, “overweight” women. These findings suggest that if you are overweight and have no health problems, you are probably better off staying at that weight (and not worrying if you gain a few pounds) rather than dieting to conform to some height-weight table “ideal.”

It’s worth noting that the negative effects of weight loss seem to exist regardless of if the weight is regained or not.

I would be remiss not to mention the dangers associated with yo-yo dieting. Too many Americans – especially fat Americans – will lose weight a few times in their lifetime, and then regain. This is referred to as “yo-yo” dieting, and it’s both common and dangerous. (Many yo-yo dieters may not think of themselves as yo-yo dieters, since there may be years between each cycle of loss and gain.) According to Case Western Reserve University’s Paul Ernsberger:

Obese humans typically show repeated loss and regain of large amounts of weight. Men with large fluctuations in weight between the ages of 20 and 40 have increase systolic and diastolic blood pressure and cholesterol. these yo-yo dieters are two times more likely to die of coronary heart disease, even after adjustment for known risk factors, than are men with stable or steadily increasing weight. Fluctuations in body weight have been shown in many other major epidemiological studies to have deleterious cardiovascular effects resulting in increased mortality.

If you’d like to maximize your longevity, probably the best thing you can do is a program of moderate exercise. This may not cause any weight loss – but no matter what your weight, even moderate exercise is likely to increase your lifespan.

3. The Idea Of “Normalizing” Eating Habits Is A Myth

The case for weight loss dieting typically assumes that fat people are fat because they eat more and exercise less than thin people; that thin people, if they ate as much as fat people, would also be fat; and that if fat people only “normalized” their eating habits, they would be thin.

Under this model, fat people eat like fat people, and so need to “modify their lifestyle” to eat “normally,” after which they’ll lose weight.

But evidence indicates that all these assumptions may be false.

First, do fat people eat more than thin people? Study after study has attempted to show that fat people eat more calories, without success. It’s true that many fat people have lousy diets with too much fatty food – but the same is true of many thin people. And, anecdotally, I’ve met fat people who were extremely healthy eaters, and fat vegans. It doesn’t appear that fat people are “eating like fat people,” compared to how non-fat people eat, in any measurable way. From Garner and Wooley:

…[A] tremendous body of research employing a great variety of methodologies… has failed to yield any meaningful or replicable differences in the caloric intake or eating patterns of the obese compared to the nonobese…

[In a study of children], Rolland-Cachera and Bellisle found that food intake was about 500 calories greater and obesity about four times more common in the lowest versus the highest socioeconomic groups studied; however, within each socioeconomic group, there were comparable levels of caloric intake among lean, average weight, and obese children. […]

…It may be concluded that nature and nurture both exert influences on body weight and that the eventual expression of obesity is a complicated matter…. Regardless of these factors, the myth of overeating by the obese is sustained for the casual observer by selective attention. Each time that a fat person is observed to have a “healthy appetite” or an affinity for sweets or other high calorie foods, a stereotypic leap into causality is made. The same behaviors in a thin person attract little or no attention….

…The major premise of dietary treatments of obesity, that the obese overeat with respect to population norms, must be regarded as unproven.

What happens when naturally thin people eat the way fat people allegedly eat? In the 1960s, before ethical rules prevented this sort of study, scientists tested this question on prisoners, doubling their calorie intake in an attempt to make them gain 20-40 pounds. From Garner and Wooley:

Most of the men gained the initial few pounds with ease but quickly became hypermetabolic and resisted further weight gain despite continued overfeeding. One prisoner stopped gaining weight even though he was consuming close to 10,000 calories per day. With return to normal amounts of food, most of the men returned to the weight levels that they had maintained prior to the experiment.

Do fat people who lose weight, do so by taking on “normal” eating habits? Some studies indicate that a high proportion of the few fat people who keep weight off, do so not by “normalizing” their eating habits, but by becoming effectively anorexic. From Garner and Wooley:

Geissler et al. found that previously obese women who had maintained their target weights for an average of 2.5 years had a metabolic rate about 15% less and ate significantly less (1298 vs 1945 calories) than lean controls. Liebel and Hirsch have reported that the reduced metabolic requirements endure in obese patients who have maintained a reduced body weight for 4-6 years. Thus, successful weight loss and maintenance is not accomplished by “normalizing eating patterns” as has been implied in may treatment programs but rather by sustained caloric restriction. This raises questions about the few individuals who are able to sustain their weight loss over years. In some instances, their eating patterns are much more like those of individuals who would earn a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa than like those with truly “normal” eating patterns.

Too many diet advocates still believe in the above myths – and that weight is a simple matter of input and output. But real human bodies are far more complex systems. From the New England Journal of Medicine (emphasis added):

Many people cannot lose much weight no matter how hard they try, and promptly regain whatever they do lose….

Why is it that people cannot seem to lose weight, despite the social pressures, the urging of their doctors, and the investment of staggering amounts of time, energy, and money? The old view that body weight is a function of only two variables – the intake of calories and the expenditure of energy – has given way to a much more complex formulation involving a fairly stable set point for a person’s weight that is resistant over short periods to either gain or loss, but that may move with age. …Of course, the set point can be overridden and large losses can be induced by severe caloric restriction in conjunction with vigorous, sustained exercise, but when these extreme measures are discontinued, body weight generally returns to its preexisting level.

4. So To Sum Up….

1) No weight-loss diet has every been scientifically shown to produce substantial long-term weight loss in any but a tiny minority of dieters.

2) Whether or not a weight-loss diet “works,” people who go on weight-loss diets are likely to die sooner than those who maintain a steady weight or who slowly gain weight.

3) For fat people (or anyone else) concerned with their health, the best option is probably moderate exercise and eating fruits and veggies, without concern for waistlines. In other words, Health At Every Size (HAES).

4) The model on which most weight-loss diets are based – in which fat people eat like fat people and must learn to eat like non-fat people – is probably a myth.

* * *

Citations

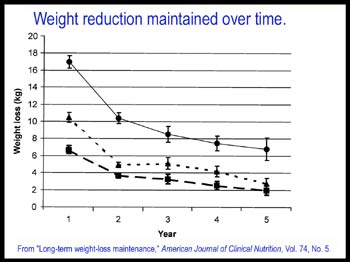

Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL (2001), “Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol 74, p 579-584

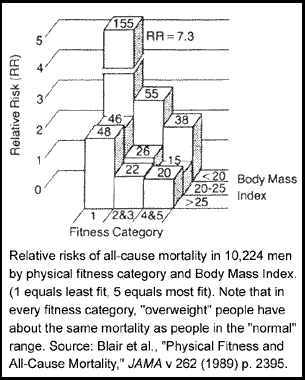

Blair, S.N., Kohl, Paffenbarger, Clark, Cooper, and Gibbons (1989). “Physical Fitness and All Cause Mortality, A Prospective Study of Healthy Men and Women,” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol 262 p. 2395-2401.

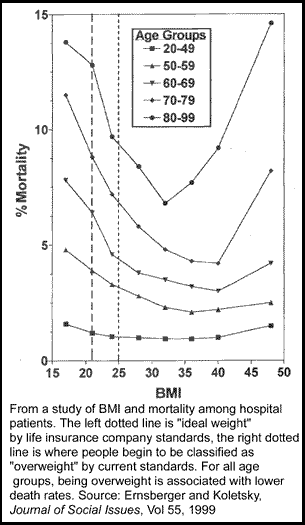

Ernsberger, Paul and Koletsky, Richard (1999), “Biomedical Rationale for a Wellness Approach to Obesity,”Journal of Social Issues, vol 55, p. 221-260.

Gaesser, Glenn (2002), Big Fat Lies: The Truth About Your Weight And Your Health, Updated Edition, Gurze Books, Carlsbad, CA..

Garner, David and Wooley, Susan (1991), “Confronting the Failure of Behavior and Dietary Treatments for Obesity,” Clinical Psychology Review, vol 11, p 729-780. Pdf link.

Kassierer, Jerome and Angell, Marcia (1998), “Losing Weight – An Ill-Fated New Year’s Resolution,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol 338(1), p 52-54.

Miller, Wayne (1999). “How effective are traditional dietary and exercise interventions for weight loss?,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol 31 no 8 p. 1129-1134

Westenhoefer J, von Falck B, Stellfeldt A, and Fintelmann S (2004). “Behavioural correlates of successful weight reduction over 3y. Results from the Lean Habits Study,” International Journal of Obesity, vol 28 (2), p 334-335

Pingback: Asymmetrical Information: Does weight loss work?

Pingback: Ezra Klein: Fat Is Good?

Pingback: cynth

Pingback: and I wasted all that birth control...: April 2006

Pingback: Repeat after me. at BABble

I hopped over to this post via BABble… And Amp, if you don’t hear it often enough, you are a genius. This needs to be said again and again and again and again until it can at least poke one tiny hole in the anti-fat, pro-diet saturation Americans experience every day.

And a shout-out to BStu, who writes an awesome FA blog. :)

I am a cardiologist and I obviously completely disagree with you.

1) Obesity has definitely been associated with increase mortality, independent of exercise (see reference).

2) I agree weight loss diets have not shown consisent long term mortality data. However, people usually don’t follow these diets long term and the cost of a trial to do so is exceedingly expensive.

Obesity is associated with an increase in diabetes, bad cholesterol, high blood pressure, gallstones, arthritis as well as psychological implications. Therefore, losing weight should reverse these and only give benefits over time — not during short term trials that have been done so far.

3) Bariatric surgery yields 50% weight loss and has yielded significant mortality benefits, and has decreased all of the above medical complications.

4) Finally, it is silly to say that scientists and doctors who have studied this all their lives are wrong. Who are you and what are your credentials. For all we know, you could work for McDonalds in an effort to confuse the public.

References:

Hu FB, Willett WC, Li T, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE. Adiposity as compared with physical activity in predicting mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 23;351(26):2694-703. PMID: 15616204

Association is not causation.

And even if it were proven that obesity was causally related to increased mortality — which, except possibly for the most extreme cases, it has not been — it still wouldn’t follow that weight loss diets are a good idea. For most people, they don’t work. There’s no point addressing a real problem (if it is real) with a non-working “solution.”

It’s certainly true that most people don’t stay on most weight loss diets long term, but that’s just another reason why it’s a bad idea for doctors to prescribe weight loss to their patients; it’s a bad idea to suggest a program that you know from experience most patients will be unable to stick with. (Too many doctors blame patients when this happens; I say that if the doctor assigns a program with a proven record of failure, and it fails, blame the doctor!)

That said, reasonable weight-loss diets also haven’t been shown to cause much long-term weight loss even among patients who don’t drop out. Certainly not enough to turn an obese person into a “normal” weight person, for instance.

Again, “association” is not causality. There are many other possible causes — not least of which is the repeated failed weight-loss diets that many fat people put themselves through.

For the large majority of fat people, weight-loss diets don’t work. Therefore, any plan of treatment that is based on weight-loss diets won’t work, either. A more rational treatment for those problems you mention is to look at preventative efforts that might actually work for most patients, such as regular exercise, or shifting to a diet richer in veggies and the like. (I won’t get into the argument over whether it makes more sense to reduce carbs or fats, other than to point out that this is a very live controversy among researchers, and not a settled question).

For those who already have diabetes, high blood pressure, etc.., there are treatments for these conditions that are effective — exercise, change in diet, medication, etc.. Harping on weight loss is pointless, because you don’t know how to make most people lose a lot of weight in the long term. No one knows how to do that.

Again, I’m asking that doctors stick with programs that have been proven to work, rather than emphasizing a program that has not been proven to work. Why is that unreasonable?

Finally, I find it ironic that you cite “psychological implications” as a problem of being fat. Being fat doesn’t cause “psychological” problems; rather, bigoted and anti-fat attitudes cause psychological problems for fat people.

Bariatric surgery also has a higher mortality risk than obesity, not to mention many other complications. Plus, it’s almost always prescribed in concert with diet changes (not just “eat less,” but also eating healthier food) and a regular exercise program, making it hard to separate where the benefits come from.

Finally, there’s also the “over what term” problem. As you probably know, a substantial number of bariatric surgery patients eventually regain much or all of the lost weight. For those who do regain, the downside of having had serious surgery almost certainly is greater than the upside of being thin for several years.

But not all “scientists and doctors who have studied this all their lives” agree with your view. As you should know if you follow the peer-reviewed literature on this, there is significant controversy over whether or not weight-loss diets should be recommended.

What there is no controversy over is the fact that no weight-loss diet has been shown to work for more than a small minority of patients over the long term. And you present absolutely no evidence in your post to convince a skeptical fat person that a weight-loss diet is likely to turn her into a “normal” weight person. As a fat person myself — and one with significant health problems — I think my most logical course is focusing on health plans that have some evidence of effectiveness. Again, let me ask: does that seem unreasonable to you?

Talk about an ad hom — as well as an argument from authority! You must realize how weak your arguments are if you’re resorting to these tactics.

It’s illogical to suggest that an argument is wrong or right depending not on the argument’s strength and support, but on the credentials of the person speaking. Throughout history, many well-credentialed people have made terribly wrong arguments in defense of a mistaken status quo.

(And for the record, no, I don’t work for McDonalds. Yeesh!)

My nutritionist to me, yesterday: “We have no data indicating that being overweight or obese affects your health. Poor diet and inactivity affect your health. These things can be, but are not always, correlated with weight.”

Mr. “Cardiologist,” how dare you contradict a dietician who has spent her life studying these things! For all I know you’re a shill for bariatric surgery companies! For shame.

Pingback: Xtinian Thoughts » Blog Archive » Weird clicking moment.

Women who are overweight are better off losing some weight, but women or girls who are average or thin should NOT buy into the “thin is in” craze! (Millions do, unfortunately.) I’ve been saying for years and years that unless women fight back against this oppressive skinniness fad which is killing a thousand or more women and girls yearly, and psychologically harming tens of millions, the dieting and clothing and exercise equipment industries will continue indefinitely to harm self-esteem, and to exploit women and girls both economically and psychologically, but, even more, physically. I truly believe that the media’s flesh-is-evil fad, that purports to get universal adoption of bony little females as the only acceptable body type, is misguided and evil, coming as it does from the distorted profit motives of the clothing industry, the dieting industry which includes diet drinks and diet pills and dieting specialists, the exercise equipment industry, and the sellers of books or videos about any or all of the above.

Women who are overweight are better off losing some weight

Saying it over and over again doesn’t make it true, no, really.

Pingback: Alas, a blog » Blog Archive » Today Is International No Diet Day

Pingback: Alas, a blog » Blog Archive » Dance Your Ass Off

At least this topic is not dying.

e.g. I was just reading:

http://meganmcardle.theatlantic.com/archives/2009/07/americas_moral_panic_over_obes.php at The Atlantic.

Pingback: Jimmy Dissects Blogger’s Disses Against Dieting (Episode 80) | The Livin La Vida Low-Carb Show

Pingback: Reading while fat, part 2 « Tutus And Tiny Hats