If you enjoy these cartoons, please support them on Patreon! Even a dollar pledge means a lot to me.

This cartoon is lampooning two things I’ve seen right-wingers do: First, claim that it’s racist that Black people but not white people can “get away” with saying the N-word. And second, look for (or invent) alternative racial slurs that they can say while remaining respectable.

Artwise, this cartoon is definitely on the “do minimal penciling, try to keep the drawings loose and lively” end of my scale. (As opposed to a cartoon like “Helping Ordinary Americans,” where almost every line, except for some of the shading, was penciled out before I did the final black linework.)

I honestly like the loose approach better, when it works well – I can’t think of a single cartoonist whose work gives me more joy to look at than Bill Watterson’s (Calvin and Hobbes), who is the king of brilliant loose lines. I’m no Bill Watterson, obviously, but that’s the ideal. But doing a loose approach feels, to me, like working without a net. If I do careful, detailed renderings, I’m less likely to be surprised, either in a good or a bad way. (And some cartoons I just think need to be more detailed, of course.)

More about the art that probably no one but me cares about: I like the look of having no word balloons in political cartoons. (Maybe it’s because I grew up on Doonesbury.) But I also like full backgrounds, and the Doonesbury approach of just having the backgrounds cut off and turn to white always strikes me as a bit clutzy looking. So here I tried having a full background, but doing it in light enough colors so the text could go directly on top of it and still be legible. What do you think? If you hate this look, let me know and I’ll be less likely to do it again. :-)

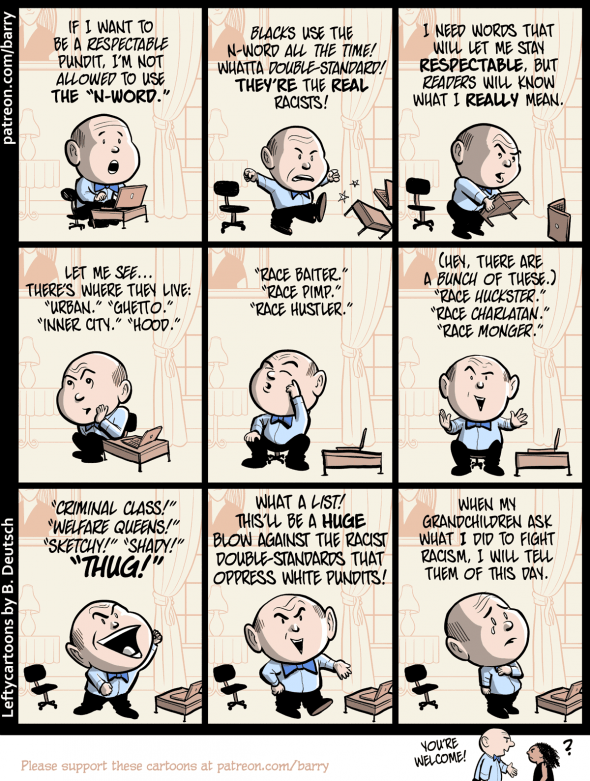

Transcript of Cartoon

Panel 1

This panel shows a balding man with a bow tie, THE PUNDIT, sitting in a wealthy-looking study, with a large curtained window, a little table with a tablecloth and a lamp, and a large framed portrait visible behind him. He is sitting in a plain office chair, at a tiny work desk, with his laptop open on the desk.

PUNDIT: If I want to be a respectable pundit, I’m not allowed to use the “N-word.”

Panel 2

The Pundit angrily kicks his little desk over.

PUNDIT: Blacks use the N-word all the time! Whatta double-standard! They’re the real racists!

Panel 3

The Pundit puts the desk back where it was.

PUNDIT: I need words that will let me stay respectable, but readers will know what I really mean.

Panel 4

The Pundit sits, chin in his hands, thinking aloud.

PUNDIT: Let me see… There’s where they live. “Urban,” “ghetto,” “inner city,” “hood.”

Panel 5

The Pundit closes his eyes, one forefinger on his temple, concentrating.

PUNDIT: “Race baiter.” “Race pimp.” “Race hustler.”

Panel 6

The Pundit’s eyes open; he’s smiling, warming to the subject.

PUNDIT: (Hey, there are a bunch of these!) “Race huckster.” “Race charlatan.” “Race monger.”

Panel 7

The Pundit, with a huge grin, has stood up from his chair and is pumping a fist high in the air. By the end of this panel he is yelling.

PUNDIT: “Criminal class!” “Welfare queens!” “Sketchy!” “Shady!” “THUG!”

Panel 8

The Pundit, looking very satisfied, speaks directly to the reader.

PUNDIT: What a list! This’ll be a huge blow against the racist double-standards that oppress white pundits!

Panel 9 (last panel)

The Pundit puts his left hand over his heart and looks reverent, a tear falling from one eye.

PUNDIT: When my grandchildren ask me what I did to fight racism, I will tell them of this day.

Kicker Panel (A tiny additional panel at the bottom of the strip)

The pundit is speaking to a Black child, who is bewildered by this.

PUNDIT: You’re welcome!

*shrugs*

We have used more polite words in europe but now those words are associated with the kind of people they have been used to describe.

Since you asked readers to play art critic:

The background in this cartoon works MUCH better than in “Helping Ordinary Americans.” The vastly overdone background in “Ordinary Americans” ran directly into the foreground objects, resulting in a visually confusing and very cluttered image. (The rear area of a drawing is called “BACKground” for a reason: It’s not supposed to distract from or interfere with the subject of the cartoon.)

So your cartoon today is a big improvement . You might have made the background SLIGHTLY darker, since it’s so light as to be barely noticeable — but keep it light enough not to encroach on the central character.

My answer to the question “Black people say ‘n****r’, why can’t we?” is this:

I have two brothers. We call each other all kinds of shit, both privately and in front of other people. It’s a joke when we do it. But someone *else* (other than some very close friends that we have known for a very long time) had better not say anything like that to any of us or the other two will take it personally. I figure this is the same thing.

Not that I think the average white person should say the “n-word”, but the brother analogy doesn’t really seem to work. You do share genetics (“race”) with your brothers, but the reason you can call each other names is because you have a direct personal history with your brothers. Imagine if you were introduced to another genetic brother you never met because he was adopted at birth into another family. You’d not feel comfortable if this brother suddenly started calling you “dumbass”. But an adopted brother could call you names all the time.

So maybe the “test” for who “gets” to say cultural stuff like that should be culture, not race exactly? Dunno.

” You do share genetics (“race”) with your brothers”

Why are you assuming his brothers aren’t adoptive?

Merely for the purpose of argument: as a semi-analog for “race”. But regardless, my point was that the reason his brothers “get away with it” is not that they are related, but that they share a personal history, which they’d have even if one was adopted (ie that’s why I said “But an adopted brother could call you names all the time.”).

As a general rule it’s still OK for in-group members to refer to themselves any way they want, and to claim outsiders can’t do so. The difficulty really arises when things get more public.

To use an analogy:

Imagine that a ton of Jews started using “kike” when speaking to each other, and when describing Jews to the public. And yet all Jews (and a significant majority of non-Jews) agreed that the use of “kike” by a non-Jew was presumptive evidence of major anti-Semitism and could easily be a serious, potentially career-ending, foul.

From a game perspective it would be a brilliant use of the social rules to gain an advantage. It would game better for Jews as a group if Jews could keep more people on their toes and if Jews could take advantage of accidental uses of “kike” to gain concessions. The public use would mean that there were more and more situations where a non-Jew would have to rewrite or moderate their speech, and would be more likely to mess up. And since the power to rule on whether a given use of “kike” would largely rest in Jews (because non-Jews shouldn’t be telling Jews what is or isn’t anti-Semitic, right?) it would overall give more power to Jews.

These days, that’s sort of where we are with “n-r.” What makes it unusual and different from words like “kike” is that it is routinely used and publicized and spoken among a lot of black people without affecting its immense stain on everyone else. So it sometimes does seem like the word is used in a very deliberate manner, where the speakers are deliberately trying to make it so the listener is discomfited and/or forced to make concessions to avoid the term. If you’re singing the CeeLo song “fuck you” in the shower, what do you do when you get to the line “that’s right she’s a gold digger / just thought you should know nigger”? If either option makes you squirm a bit, I suspect CeeLo intended that result.

I think it’s brilliant gaming of the system and I respect the black community for managing it so well. But while I’m used to it for “n-r” (probably because I have been trained that way my whole life) I am still a bit concerned that the strategy will become more common. Weaponized language is sort of like the ultimate in cultural appropriation claims and it seems that any expansion would probably harm communication.

First, for the record – to paraphrase the Marx Brothers, according to my mother the man who lived in my house our entire childhood was our biological father.

Second – what defines the bonds of brotherhood to me are the shared experiences, we had and the shared principles and ideals we lived by while growing up; our culture. Note that I included not only the two people I share genetic material with but “some very close friends that we have known for a very long time”. Brotherhood is more than genetics. There are people I call “brother” that I share no genes with.

But isn’t it true, then, that the use of a term that is viewed as a racial epithet is acceptable when used by someone of the same race is because it’s presumed by the people involved that due to their same race they share similar experiences, etc. It’s not precisely the same thing, but I don’t think it has to be to be close enough to explain the phenomena.

For what it’s worth, RonF, I agree with your take on this issue.