This cartoon was drawn by Becky Hawkins.

If you like these cartoons, you can help us make more by supporting the Patreon!

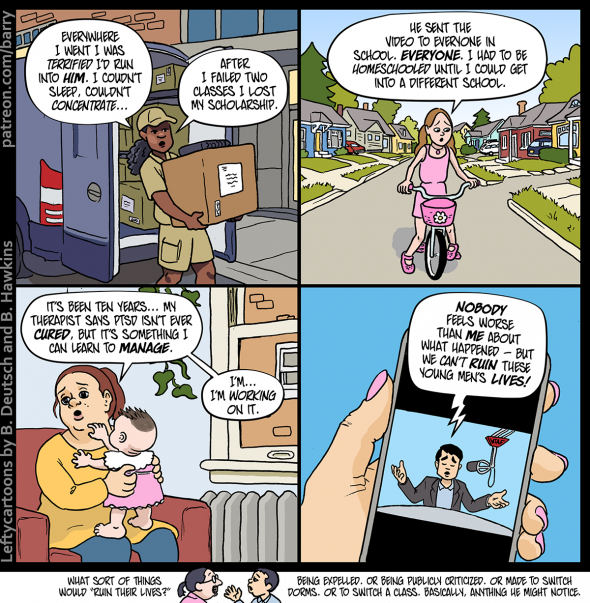

Anytime a male student is accused of sexual assault – or even when discussing things more abstractly, like how campus justice systems should treat a student accused of rape – we hear the same argument: “We can’t ruin his life.”

In context, “ruining his life” is a statement that can mean many things. Everything from a long prison sentence, to being expelled, to being made to switch dorms or classes, to losing a place on a sports team, to even being investigated in the first place.

I actually do take their point. Men falsely accused of rape do exist.

But.

But victims of rape also exist. Although being a victim of rape is terrible in any circumstance, it can make things even worse when schools refuse to take action to protect victims, for fear of inadvertently punishing a falsely accused man. Some victims have had to take classes with their attacker, or live in the same dorm.

There is no solution that completely avoids unfairness. But making schools shouldn’t do anything that impacts the life of an accused rapist our top priority doesn’t reduce unfairness. It just transfers it. It moves unfairness away from accused rapists by piling even more unfairness onto rape victims.

This is even worse when we consider that rape is a much more common crime than false reports of rape are. We can’t use this principle to judge any individual case, but it’s safe to say that a large majority of rape reports are true.

Figuring out school justice systems is complex. But schools effectively treating the protection of accused men as their first and foremost goal, making the protection of victims a distant second priority, is a bad solution.

When I was thinking about how to approach this cartoon, I wanted to push back subtly against the “ruined lives” narrative. People are hurt badly, and the course of their life may be altered. But for most, their lives go on. The two women and the girl in this cartoon are all still having lives, and perhaps very good lives, but that doesn’t mean that they’re entirely okay and uninjured.

And frankly, the same is true of a man who is kicked off the football team or even made to switch colleges. The course of his life has been altered – in most cases, deservedly so – but his life is not “ruined.”

I’m not surprised that Becky chose to draw this one. It aligns with Becky’s politics, of course, but it also aligns with Becky’s love of drawing different characters and settings.

Just look at that background in panel 2! She drew seven houses and three cars like it’s nothing. God, how I hate Becky.

(Kidding!)

[Becky here! Barry is right–I really enjoy drawing different environments! Google maps was my friend for this cartoon. I like opening Google Street View and clicking around different neighborhoods to find the right setting. If I find an area I want to use in a cartoon, I’ll save screenshots to look at later. Panel 1 is a street in Northwest Portland with lots of shops and tall apartment and office buildings. Panel 2 is based on a sleepy street in Southeast Portland. (Instead of copying the street exactly, I clicked up and down looking for an interesting collection of houses.)

The guy in Panel 4 is modeled after Ben Shapiro. I saw a photo of him speaking into a microphone with a radio station written on the arm. So if you zoom in close enough, the red part of the mic arm says “WTAF.”

I’d actually blocked out the memory of drawing the hand holding the phone. It took so many tries to get it to look right. When I opened the file folder for this cartoon and saw all the reference photos and stock photos I ‘d saved of hand-holding-a-phone, it came flooding back. I’m pretty sure I spent more time trying to draw that dingdang hand than I did drawing seven houses and three cars!]

Barry here again. Oddly enough, I love drawings close-ups of hands holding smart phones, which is probably why I put them into my cartoons so often.

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

This cartoon has four panels, each showing a different scene. A tiny additional fifth “kicker” panel is under the bottom of the cartoon.

PANEL 1

A Black woman in what appears to be a UPS or UPS-like uniform is standing holding a large box with an address label on it, and an electronic clipboard device on top of the box. Behind her we can see the open doors of the back of a van, and inside the van, more boxes to be delivered. She’s parked on a city street, in front of the entrance to a brick building. She speaks directly to the viewer, with a calm but downcast expression.

WOMAN: Everywhere I went I was terrified I’d run into him. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t concentrate…

WOMAN: After I failed two classes I lost my scholarship.

PANEL 2

A light-skinned girl is on a bike, on a suburban-looking street. The street is clearly residential, and is lined with cottage-style houses. The girl’s clothing is pink, like her shoes and the pedals and basket of her bike.

She’s facing the viewer, but looking downward with her eyes to avoid looking directly at us.

GIRL: He sent the video to everyone in school. Everyone. I had to be homeschooled until I could get into a different school.

PANEL 3

A light-skinned woman sits in an armchair, looking vaguely into the air as she talks. She’s wearing jeans and a yellow top, and holding a baby, who is standing in her lap and doing that cute-but-annoying thing babies do of patting the face of the person holding them while that person is trying to talk. The baby has a pink skirt and is cute.

A plant hangs from the ceiling. Judging from the brick building next door we can see out the window, and the radiator below the window, this is probably an apartment in a city. Her expression is a bit sad, but not over the top or panicked.

WOMAN: It’s been ten years… My therapist says PTSD isn’t ever cured, but it’s something I can learn to manage.

PANEL 4

A hand with pink, smoothly filed nails holds a smartphone. On the smartphone, a pale-skinned male podcaster or radio host is sitting at a table, a professional-looking microphone in front of him. He’s wearing a jacket over a blue collared shirt (no tie), shrugging with a sad-but-calm expression.

MAN: Nobody feels worse than me about what happened — but we can’t ruin these young men’s lives!

TINY KICKER PANEL UNDER THE BOTTOM OF THE CARTOON

The man from panel 4 is talking to Barry, the cartoonist.

BARRY: What sort of thing would “ruin their lives”?

MAN: Being expelled. Or being publicly criticized. Or made to switch dorms. Or to switch a class. Basically, anything he might notice.

It’s interesting that different artists find different things more or less challenging. I could have made a decent line drawing of that street myself (it’s just geometry!), but the girl on the bike would be utterly beyond me.

As for the theme of the cartoon, I was under the impression that the “ruining his life” argument was generally raised when it came to a conviction, especially one that carries a prison term. That’s quite different from making a sex offender change schools. The penal system does ruin lives and I wish we had something better — for all offenders, of course, not just privileged white males charged with sex offenses. But separating an offender from their victim isn’t punitive; it’s restorative, and it doesn’t even carry the same lifelong consequences that other penalties might have.

Accusations of rape are something that the police&judiciary should handle.

It shouldn’t be up to the school to determine whether the charges are valid or not.

Polaris – do you think schools should not be allowed to enact disciplinary measures against their students who break school rules? Or do you think that accusations of rape/sexual harassment/revenge porn/etc. are a special category? So that, say, a school is within its rights to expell a student who refuses to adhere to the uniform policy, but it should not expell a student who distributed a sexual video of another student?

This reminds me of when I heard someone argue that the CEOs of the major banks responsible for the 2008 recession shouldn’t face criminal prosecutions let alone go to prison, even though they committed fraud, because being prosecuted is scary.

See MAHANOY AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT v. B. L.

Public high school student B.L. didn’t make it onto the school’s varsity cheerleading team and so—off-campus and outside of school hours—made and distributed a Snapchat message using vulgar language and gestures criticizing the school and the school’s cheerleading team. School officials suspended B.L. from the junior varsity cheerleading squad, stating the post violated program rules and the school’s rules for student-athlete conduct. B.L. sued.

SCOTUS ruled that the punishment violated B.L.’s free speech rights, emphasizing that the conduct in question happened off campus and outside of school hours. The court reasoned that the school’s interests—including teaching good manners, preventing classroom disruption, and preserving team morale—did not outweigh student’s interest in free speech.

But SCOTUS left the door open to reaching a different outcome under different circumstances. “[T]he special characteristics that give schools additional license to regulate student speech do not always disappear when a school regulates speech that takes place off-campus.” Examples of “off-campus behavior” that “may” call for school regulation include severe bullying or harassment targeting particular people, threats aimed at teachers or other students, participation in online school activities, and breaches of school security devices, including material maintained within school computers.

Eytan @3

I know this was at Polaris, but if you don’t mind, I’d like to take a swing at it.

The short answer is that it’s going to be complicated, and it depends.

Right off the top: I think that including revenge porn in this discussion is a classification error. Revenge porn is not rape. That doesn’t mean it’s good, but not all bad things are the worst thing possible. And the process for those cases should be different… It’s relatively easy to figure out the facts, particularly when there are digital records, and in cases where there are no revenge porn laws, perhaps the school should be the agency to act. And if I have to pin down a general rule for situations like this that’s going to be my very blurry line: There should be an identified agency best able to deal with different classifications of issues, and that agency should have something approximating sole responsibility for the process.

To an extent, we already do this: If a student is accused of murdering another student we don’t expect the school to act as the agency involved in fact finding or justice. In a perfect system, the police would arrest the student, an investigation would take place, and the system would provide an answer. If in fact there’s a determination that the accused student did commit murder, then the school’s actions are moot… The student is going to jail regardless of whether or not the school expels them. If at the end of the fact finding process the accused is found not guilty, then I don’t know if it’s the school’s job to overrule that, even in their narrower format. That’s obviously less than ideal, particularly if the accused actually did commit the murder, but I don’t know what the reasonable alternative is. How does a school take it upon themselves to say that they did their own investigation and determined that the accused student did commit murder, while the student stands acquitted?

If you feel like that didn’t clear anything up, I’m sorry, but rape cases are worse. Murder is almost always illegal and a dead body is pretty good evidence that at least a homicide occurred, but the vast majority of sex is consensual and fun, and the only things that differentiate normal sex acts from rape are the victim’s lack of consent and the perpetrators reasonable knowledge of that lack of consent. This makes rape cases notoriously hard to prosecute. Everything I just wrote about murder applies to a rape case but the facts are much less clear and that means that victims are much less likely to get justice.

And I think that’s why we’re having this conversation, victim’s rights groups generally aren’t happy with that, and so the push seemed to be an erosion of process: They weren’t seeing enough convictions, so the plan was to game the system in a way that hurt the people that they legitimately see as rapists the most, functionally abandoning the legal system in favor of educational tribunals, the innocent people they hurt along the way be damned.

I’m sympathetic. I imagine that it might be easier to ignore the suffering of a minority of innocent accused when part of a group of innocent sufferers in search of justice. But two wrongs don’t make a right. And doing the right thing the wrong way is still wrong… And more bumper stickers. I honestly don’t know what you say to them, it’s rough. I don’t judge them, but I disagree.

I think the answer, if one exists, is to Schrodinger the situation, and act as if the accuser is telling the truth from a support perspective and assume that the accused is innocent from a punishment perspective, at least until better information comes out. Give the victim options, do they want to return to class? How is that facilitated? Do they need resources to talk to? Can accommodations be made? If the victim can procure a restraining order, then all of a sudden this becomes easier: the accused has to stay X distance away, can their courses be taken by distance education? This isn’t perfect, obviously, and sometimes it’s going to be really hard to reconcile sometimes, but I don’t know what the better alternative looks like.

Does that make sense?

Corso – I brought up revenge porn because the cartoon’s second panel is about a video. Polaris narrowed the question to one of rape, but that’s not what this cartoon is about.

As for what you are saying, I agree that the difficulties you point out are real. But – and this is crucial – schools are not courts. The principles of innocent until proven guilty and reasonable doubt do not apply to schools. You and Polaris are correct that the school should not decide whether a student is guilty of a crime in the eyes of the law. You’re right that the school should not act as a replacement to the legal system. But a school also has the obligation to protect its students from other students. And to do that, the school has the obligation to determine whether a student is a risk to other students.

I’m not advocating for a system in which accusations are automatically taken to be evidence of such risk. But I believe that in any situation where there’s a reason to suspect that one student is a risk to the well being of another – be it because of sexual harassment, rape, assault (sexual or other) or bullying – the school has a duty to intervene, without having to wait for the legal system to make a determination. And the school’s standards of evidence do not need to match that of the legal system. It’s enough that the school determines that the risk is plausible, not that it is certain, to act on it.

I’m not saying that the situation is easy, or that there is a way that schools can magically ensure justice where the legal system cannot. But neither do I think it’s correct to make school action contingent on legal action. And once you accept that schools need to make their own determination, then Barry’s point holds – the driving principle cannot be that protecting the accused is more important than protecting the accusers.

As a minimum, I’d expect a school to treat allegations/evidence of sexual assault, sexual harassment or rape by the same principles they treat allegations of bullying. If you accept that a school has the right (and responsibility) to punish bullying behaviour even without legal intervention, than I don’t see why you’d limit its ability to punishing sexual assault, sexual harassment, or rape. If you don’t accept that a school can punish bullying behaviour without a court ordering it to, then I don’t think we can find common ground.

The problem with handling accusations through extra-judicial proceedings is that the closer they come to formal disciplinary hearings, the more likely it is that they will affect the subject’s legal right to due process and so forth. This is quite a problem: things like dorm and class reassignments really shouldn’t be treated as weighty issues of justice, but if the registrar (or whatever the US equivalent is) says that they’re reassigning someone’s accommodation for being a sexual harasser then I think the subject would quite reasonably want a chance to appeal that determination – not the reassignment necessarily; just the fact that their file now has a note on it that they’re a sex pest.

What decision-making bodies of this sort should do is scrupulously avoid making findings of fact: that’s a matter for a court. When they see the need to reassign a student it would be enough for them to say that they made the decision in response to a complaint and, if the complaint is serious, refer it to the police.

I have both a son and a daughter. If my son was accused of sexual abuse I’d insist that he be given the presumption of innocence and that no measures punishing him be taken either judicially or extra-judicially until he was convicted of a crime. If my daughter accused someone of sexual abuse I’d want his balls cut off. So I have a conflict here.

It makes no sense to say that the only body capable of making a finding of fact is a criminal court.

Different adjudications will impose different standards of proof, and may also impose different standards of evidence.

For example, any crime against another person can produce a civil trial as well as producing a criminal trial, and the standards of proof and of evidence are different between the two. Very few people would argue that you should only be allowed to sue someone in civil court after they have been successfully convicted. If they are convicted, you can use that in a civil case, but if they are acquitted, that very much doesn’t mean they’ve been proven innocent, so you can sue for damages against someone who was acquitted of committing a crime against you. It is easily possible for there to not be proof beyond a reasonable doubt of guilt, but for there to still be a preponderance of evidence of guilt.

Likewise, a school probably should use something closer to the civil standard of proof (preponderance of evidence) for expulsion (a punishment far closer to a civil penalty than to imprisonment), and something lower than that for lesser measures such as requiring someone to move out of a particular dorm, change classes, or to place an equivalent of a restraining order (many states use ‘reasonable grounds’ as the standard of proof for restraining orders). Expulsion is a reasonable punishment for any behavior that seriously violates the contract between the student and the school, while lesser actions are necessary to accommodate the competing needs of different student.

I’m very suspicious of people who suddenly think that “criminal prosecution or nothing” are the only correct response for schools to student infractions when those student infractions are sexual harassment or sexual assault. Schools punish plenty of infractions that don’t even rise to the level of criminal activity, and it makes no sense to say that schools must do nothing if a student is alleged to have committed an infraction that also happens to be potentially criminal. If someone engages in harassment of a fellow student that can’t be considered a crime, but does violate the school’s code of conduct, then the school can adjudicate the case, but if the behavior is severe enough that it is also criminal, then suddenly the school can’t do anything for however long it takes the case to work through the criminal justice system? How is that possibly a coherent or appropriate rule?

If a student cheats on an exam by stealing their professor’s computer or breaking into their google account, would anyone really require that the student first be prosecuted for theft or hacking before the school is allowed to punish them for cheating on the exam?

It would be useful to have a concrete example to discuss. Otherwise, I think we’re just shadow-boxing.

But to continue at the level of generality, here’s how things look to me: People have patterns of behavior (classes, dorms, etc.) that arise in the absence of accusations of wrongdoing. Now someone makes an accusation. In the absence of intervention by some authority, the accused party will likely continue the same patterns as before–and it will fall to the (alleged) victim to make any necessary changes. But for the authority to take action, the authority must first have grounds to do so. Amp’s cartoon notes the harm that befalls an innocent party–but it says nothing about how to resolve questions of FACT. And it’s a harsh reality to face, but compassion is not a substitute for knowledge.

I see a sliding scale, where slighter interventions can be justifies on the basis of mere rumor, while more serious and targeted interventions may require a felony conviction. As Amp notes,

I find this a useful insight: Can we identify remedies that do not (publicly) focus on individuals? For example, if a teacher heard that a given student was planning to humiliate another student in class, that teacher might simply elect to refrain from calling on the troublemaker–or contrive to have the student pursue some project outside of class that day. Or maybe a high school teacher makes a habit of shuffling seating assignments each week or so–and uses this regular break of routine as a mechanism to keep two students far away from each other. In each case, there is no accusation and no confrontation, and little harm–so even slight evidence might justify these tactics.

Slightly more confrontational, an authority could announce a new policy designed to avert problems in the future, without affirmatively claiming that problems arose in the past. “From now on, students wanting to go to the bathroom must take two friends with them.” Again, this remedy could be justified even in the absence of evidence of past wrongdoing.

Or a school could adopt a presumption that all penetrative sex is rape; people who pernitrate their classmates (and leave evidence of the fact) place themselves at the mercy of their lovers, without recourse. This would seem like a policy designed to address the dynamic Amp identified in the quoted passage above.

Stronger still, a school could close its dorms and put all classes on-line.

But here my imagination fails. I struggle to identify circumstances under which an authority would expel a specific student from a class, dorm, or school without some pretty substantial evidence of serious wrongdoing. And, ironically, I’d be more willing to take steps against a student accused of bullying than a student accused of rape–precisely because rape is such a serious offense. If I publicly sanctioned someone accused of rape, it would appear that *I* was making the accusation–and I could be liable for defamation if I couldn’t back up the claim. And I don’t think that advice such as “scrupulously avoid making findings of fact” would help. If I publicly deviate from the status quo (by, for example, imposing a sanction on someone), an aggrieved party will ask why–and will ask the judge to compel my answer.

Ok, how ’bout this: The school could have a policy that an accusations of misconduct would result in the accused having to change dorms and classes–as well as the accuser. This would strengthen the authority’s claim that, in imposing the sanction, it was not lending credence to either claim. (Alas, this policy might also give incentive to a student who was struggling with a professor or roommate to seek an escape by making a false accusation against a classmate….)

Finally, to people who argue that authorities should feel free to impose sanctions in the absence of knowledge, recall that black people are 14.2% of the US population, but RAINN reports that black people are convicted of 27% of rapes (along with another 9% committed by “unknown race” or “mixed). Admittedly, this reflects convictions, not accusations. But wherever there is a policy authorizing sanctions, I expect that policy to be imposed most stringently against black people–even when we make a rigorous effort to enforce due process. If we relax due process, what outcome should we expect…?

I agree with the view that authorities should not make defending the accused their primarily objective. Instead, their primary objective should be to create a good status quo–and this may include adopting policies that will apply under circumstances of uncertainty amid accusations of misconduct. But, having established these policies, I would not otherwise deviate from them in the absence of FACTS, and fact-finding typically requires due process and time.

I disagree that awaiting due process causes unfairness to be transferred to victims. Rather, this policy leaves the unfairness where it is, at least for a time. Yes, that outcome offends our sense of compassion–but compassion is not a substitute for knowledge.

True. OTOH, the processes and standards for trying and finding facts in both a criminal and a civil court have been developed over centuries and are subject to multiple levels of testing and review by higher courts and by the defense. Many of the objections to administrative procedures used in universities are based on flaws in those processes and the inability to have them reviewed or tested.

“it’s a harsh reality to face, but compassion is not a substitute for knowledge.”

I am not sure I 100% agree with this. Isn’t compassion a form of knowledge, e.g. knowledge of the experiences and consequences of trauma? Isn’t lack of compassion actually something that is missing from a lot of so-called knowledge-based processes?

Men can be sexually assaulted – and in fact are more likely to be victims of sexual assault than victims of false accusations. Women can also commit sexual assault or be falsely accused (admittedly, most of the cases I know of false accusations surround abuse of children in daycare).

What if we didn’t respond to sexual assault accusastion in this binary way – either the accuser must be a horrible liar trying to ruin a good young man’s life or we need to ruin the life of the monster rapist.

What if we focused on protecting victims and rehabilitating perpetrators?

Better yet, what if we focused on prevention, by teaching respect for the bodily autonomy from a young age and disciplining children in an age approprite way for infractions? When girls were groped at school when I was growing up, we’d be told “that means they like you” or, later in high school, we’d get written up for dress code viloations. In any case, nothing would happen to the boys. Some of those gropers went on to be rapists (four were convicted of gang raping a mentally handicapped girl shortly after we graduated high school). Could that have been prevented if they had simply been given detention for groping girls when they were in school, rather then being taught that they had the right to take what they wanted from female bodies?

Kate, I think I agree. When we focus on the punitive side of justice we tend to ignore the need for rehabilitation. Also, the prospect of a criminal conviction makes it more likely that the accused will fight the charges, which will be traumatic for the accuser and, if the defendant prevails, will sometimes mean that a guilty person has been wrongly exonerated. Sometimes people really do need to be locked up; sometimes they really do need to have a conviction recorded against them. But we also need to have ways to handle cases that don’t rise to that level. We should be spending vastly more on rehabilitation and mental health for offenders anyway; it’s crazy that we don’t even contemplate it unless they’ve entered the criminal justice system.

Charles @10

I think this may have been directed at me, and if it was, I didn’t say that. nobody.really’s comments @11 almost perfectly mirror my own, and I think they expanded the ideas well. But I did say that my “very blurry line” was that “there should be an identified agency best able to deal with different classifications of issues, and that agency should have something approximating sole responsibility for the process.”

It seems to me that there are often too many cooks in the kitchen, and generally, we should defer to the highest authority applicable, which would ideally be the group best set up to work the situation. Of course schools could act as fact finders, but are they really the best equipped, most able people to do so? They’re biased, primarily concerned with the outcomes for the school, and educators, usually with someone between little and no training in dealing with these situations.

And when there isn’t that? Look, nothing you said was incorrect in and of itself, obviously we don’t need to have a criminal conviction for civil liability, but while there are all kinds of variations on the theme, the most common fact pattern is that two people are alone in a room, a sex act occurs, one party says it wasn’t consensual and the other says it was. A preponderance of evidence with that fact pattern is hard to arrive at. It’s why these cases are so frequently unsatisfied. That’s not a flaw of the system, we literally do not know what actually happened, and it is better, not good, but better, for guilty people to walk free than for innocent people to be punished. There is no greater injustice.

I explicitly did not say that. I said that we should support the victim to the best of their ability while doing as little as possible to the accused until a finding of fact came out. Schedules could be rearranged, dorms could be changed, these are not life altering events, and a starting point. On the other side of that, when you said expulsion was “a punishment far closer to a civil penalty than to imprisonment”, I agree that it’s closer, but it’s not the same, and for someone decrying a black or white view of a situation that I don’t think anyone has actually taken, perhaps some nuance to your position is in order. Wearing my views on my sleeve, Education is important, and a sexual violence accusation can permanently sideline lives, I think we ought to be more certain than “it may have happened” or even “it’s likely that it happened” before sewering someone’s life trajectory. Like I said, and to be clear: There are absolutely things that the schools can do, moving dorms or rearranging schedules seems very reasonable, but expulsion is, in my opinion, an order of magnitude more serious that you seem to think.

“What if we focused on protecting victims”?

Many victims do not feel protected as long as their attacker is not incarcerated, and often criticise failure to incarcerate their attackers as something that makes them feel unsafe.

Preponderance of evidence is literally the standard rule for expulsion from college. But some of us suddenly discover it is too severe of a standard when sexual assault is the topic…

NR also stands pat on explicitly thinking that probable bullies should be punished, but probable rapists should walk free because being punished for being a probable rapist is such a terrible thing. So that’s panel 4 of cartoon there, enacted and endorsed by the commenters here.

Satire is dead.

But, it doesn’t follow that the testimony of the alleged attacker and the alleged victim must be given equal weight. The alleged attacker has a clear motive to lie. In the absence of a clear motive for the alleged victim to lie, the victim’s testimonly should be given more weight. I don’t think it generally is, but I think it should be.

Sure. But in the current situation many are called lying sluts AND fail to see their atackers incarcertaed. Any concern for the protection of victims at all would be an improvement over the current situation.

And, rape is so common and committed by so many seemingly nice, personable young men, that I don’t think it can be addressed without extending some sympathy towards the perpetrators. Especially because often even the victims liked, or even loved the person who attacked them and feel ambivalent, or even aversion, to ruining their lives. This was my experience, and it is more common than those who have not experienced it might think.

And, as I said above, boys are often taught that they have the right to touch girls as they wish in school. They are often taught that girls should cover up to avoid arousing them. Our culture DOES tell them that it is o.k. in hundreds of tiny ways. So, I DO have sympathy for them. Boys who sexually offend as teens and who are caught and disciplined have a very low recidivism rate as adults. So, accountability doesn’t ruin their lives. It makes them better men.

I don’t think the current problem is lack of sympathy towards rapists, quite the opposite.

Currently rapists benefit from an incredible abundance of sympathy, not least that they cannot be held to account for rape until an incredibly high bar is passed, a bar so high that practically for something like 95% of rapists it will never be reached.

I can’t see how extending them even more sympathy will solve anything. I mean on a personal leave we can sympathise, or not sympathise, with who we want, but talking about institutions, I think we need to sharply throttle back on the sympathy extended to rapists.

But, in most of those cases (not all, I know there are some exceptions), sympathy isn’t being extended to someone who people see as a rapist. Sympathy is being extended to someone the community sees as being falsely accused of rape. There is a big difference. The current problem is that people are not willing to admit how common rape and rapists are.

But even when a man has been convicted the sentence is often extremely brief or even non-custodial. And once he has served his sentence he is then allowed to re-enter society with no restrictions, or at best very weak restrictions. So even when a man is “officially” a rapist, e.g. the facts have been validated by a court system that is strongly biased towards protecting rapists, we still have to act as if he is not one except for what is usually a very brief period when he is subject to some kind of incarceration or restriction.

I’ll just say that when I was in high school a student DID murder a fellow student off school grounds, and the murderer was suspended while the investigation was ongoing once they became a suspect. When I was in high school none of the people I knew who were sexually assaulted (up to and including rape) reported it, so it is unclear what would have happened, but I am thinking not suspension (which is probably why no one bothered to report it – I know I didn’t report mine, since I figured it would mostly hurt me and do nothing to my assaulter).

As for what should happen, I don’t think that it is too harsh to impose a no contact order such that the alleged victim does not need to see or otherwise interact with their alleged assaulter. For classes, that might mean the alleged assaulter has to withdraw or not attend class until an investigation is complete. For a dorm situation, that might mean moving the alleged assaulter – there is no need to make public why. Students change dorms for many reasons, so that isn’t particularly damning.

Most cases would likely end up as “they said, they said”, since the fact that the two people were known to be in the same place at the same time is relatively straightforward to establish, while the issue of consent is much harder to prove one way or another. Personally, I would lean towards assisting the victim here, and maintaining a no-contact rule, even if that inconveniences the alleged assaulter.

I also have a son and a daughter, and I don’t want either of them assaulted nor do I want either of them to assault someone. We discuss consent and personal safety, both separately and together as a family. And having seen the way the world has not changed enough from when I was a student, I would likely counsel my kids to NOT report unless they had some sort of evidence beyond “they said, they said”. I feel no shame in protecting them from having their lives revolve around a horrible incident, possibly for years, for the tiny chance for justice. Reliving the assault and being re-victimized by the investigation are just not worth it. Better to just work on recovering from the event and living their own lives.

That’s not a perspective I often hear. Perhaps this just illustrates how people in different environments encounter different viewpoints.

I more often encounter perspectives such as this:

For example, New York laws can bar sex offenders from living within 1000 (lateral) ft of a school or facility that cares for kids. This may seem like a workable policy in the suburbs–but if you live in dense urban communities, you may discover that this prohibition blankets virtually the entire city.

And those are just the legal consequences. According to the American Civil Liberties Union,

I won’t (at this time) ask for compassion for sex offenders. But I will ask that people base their opinions on accurate information.

Yes I mean we can of course find isolated instances of rapists facing extrajudicial punishments beyond what the justice system imposes.

But given that there are many cases of rapists having non-custodial sentences or only serving a year in prison, I’m not convinced that these particular instances establish a pattern.

I share the view that we should not base our conclusions on isolated, atypical examples. And I continue my campaign to encourage people to base their opinions on accurate information.

To this end, please note that the United States Sentencing Commission reported that, for 2020, 99.5% of sexual abuse offenders were sentenced to prison and their average sentence was 201 months (almost 17 yrs).

Nobody.Really, I suspect that a typical rapist serving less time would be one that made a plea bargain and got sentenced to a lesser charge, and thus wouldn’t necessarily be included in those statistics. Any rapist who isn’t offered a plea bargain would be one that prosecutors have an iron-clad case against, and who they expect to be unsympathetic to a judge and/or jury.

Also, those stats only include federal courts, not state courts. Most “typical” rapists who are tried, are tried in state courts. Most of the people in the federal stats you linked to were either people who make child pornography, or people who crossed state lines to have sex with a minor.

That said, I do think it’s probably the case that rapists who are tried and convicted of rape are punished pretty harshly, although there are some egregious exceptions. But the number of rapists who aren’t tried and convicted of rape – due to plea bargains, or police deciding they don’t have a strong enough case, or prosecutors deciding the same, or simply because the rape is never reported – is far larger than the number who are tried and convicted.

Thank you, Amp.

You may be right about disparities in sentencing between federal and state courts; I don’t know.

But the United States Sentencing Commission reports that “10.1% of sexual abuse offenders were convicted at trial, compared to 2.2% of all other federal offenders.” I read this to mean that 89.9% of people convicted of sex abuse pled guilty–and this STILL resulted in an average sentence of 201 months. But maybe there’s another way to read this?

True enough, the category “sexual abuse” includes crimes other than rape; I expect that’s true in both federal and state jurisdictions. The Commission notes that rape convictions carry an average sentence of 192 months (16 yrs). So, ironically, a person facing a federal charge of sexual abuse might want to plea bargain DOWN to a mere rape conviction, thereby reducing his average sentence by 9 months.

But there could be some statistical flukes here, as when people plea-bargain down from a sexual assault to a mere assault; I expect that their data would no longer influence these averages (but presumably would get including in the sentencing data regarding assaults).

As Ken said to Barbie, “Social science is hard.”

I don’t think we, as a society, have figured out what to do with offenders. Is 201 months right? Right for what? I think locking someone up for that amount of time is horribly abusive. It certainly doesn’t help the victim in any meaningful way. I don’t know what we should be doing instead, mind, except that it would probably involve supervision, and counselling, and reparations.

I totally agree, Joe. I want the country to get away from carceral solutions as much as possible; far fewer people should be sent to prison at all, and those in prison should typically be there for years less than they are under the status quo.

However, I avoided bringing that up in my prior comment because I don’t see any reason to begin that discussion in a thread about rape and sexual assault. We should be having that discussion about ALL prisoners, or maybe we should discuss the low-hanging fruit – nonviolent criminals – first.

“It certainly doesn’t help the victim in any meaningful way.”

I think the most important thing is to listen to victims and listen to women.

And while it is not unanimous, a significant number of victims and women say they do want rapists imprisoned, or they want them to be imprisoned for longer than they currently are. I think we shouldn’t be selective in only listening to the victims/the women who agree with our preexisting beliefs.

Thanks, Ampersand. Yes, my remarks about sentences are directed to all crimes, not rape in particular. It’s hard to articulate a coherent standard for addressing crime because, I think, we mostly want two things: the bad thing not to have happened; and the bad thing not to happen again. We can’t do much about the first (therapy only goes so far, and restitution is rarely substantial enough to be meaningful) and we seem reluctant to make the social changes that would help ensure the second.

Gorkem – I agree, but also, people usually choose from the options they’re aware of, not from options they haven’t yet heard of.

Mary Koss (a feminist scholar who studied rape issues for decades, although she may be retired now) pointed this out about “restorative justice” as an alternative to the traditional court system – that a significant number of rape victims do prefer the restorative justice alternative when it’s presented to them as an option. And some studies have show that some women do get a much greater sense of closure from going through the restorative justice process.

Of course, not all rape victims would choose that, and they shouldn’t have to. But I think it should be an option.

I think one thing that virtually all crime victims would agree on is that they wish the crime had never happened in the first place. When we reach the point where we’re discussing punishments, society has already failed to protect the victims adequately.

We need to focus on prevention. That means making sure every child is taught their rights as a human being and their responsibilities to respect the rights of others. It means certain, proportional consequences for bullying in schools. It means having counselors in every school to help children who have behavioural problems. It means having after school programs, all the way up through high school, so children and teens have adult supervision and constructive activities to participate in.

If we put more resources into schools, mental health care and support for families, we will need fewer police and prisons.

For what it’s worth, Harvard’s Steven Pinker argues that societies have grown less violent over the millennia. More recently, crime in the US has fallen dramatically since the 1990s–although the murder rate began increasing again around 2020. Wikipedia cites various theories trying to explain these trends; they don’t focus on the variables cited by Kate.

Oh sure! Crime has gone down. Rape even is far, far less common than it was in the 1960’s. And many of those theories cited in the Wikipedia article might be correct.

Although my knee-jerk reaction is to say that public education has gotten worse since the early 1990’s, on reflection that might not be true on the points of most concern to this issue. I get the sense that there has been a pretty radical change in attitudes towards bullying. When I was growing up in the 70’s and 80’s, I was almost universally told by parents, teachers and administrators that if I didn’t want to be bullied, I needed to try harder to fit in. My sense from popular culture is that that sort of victim-blaming is less common now, at least in liberal areas. I think there is less tolerance for interpersonal violence in school as well. It may also be that supervision of children after school and on weekends is more robust, particularly among the middle class and wealthy. I do recall controlled studies in which half the schools had after school programs introduced, and were compared with schools with similar demographics but no after school programs and the number of students who became “involved with the criminal justice system” went down in the schools with after school programs, as did pregnancies among the girls, but I have no idea where to find it now.

Charles @ 18

I tend to find that when the other person in a disagreement has to mischaracterize what you’ve said in order to debate your point, they probably know, whether they choose to acknowledge it or not, that you have a point. This isn’t what I said. I can’t speak for NR, but I don’t think that was his point either. Our comments speak for themselves.

The conversation seems to have moved on, and I find it interesting. There are positions out there that “the left” as an ephemeral, general thing have that aren’t easily reconcilable. Don’t get me wrong… Righties have these issues as well, but I’m going to focus on left issues because I think that’s what the crowd here (generally) can speak to, and the forced reconciliation of these issues are always interesting.

Take guns, for instance, it seems facially to be inconsistent to hold the views that private individuals should not hold guns, and that some amount of police officers are ruthless thugs. “only cops should have guns” doesn’t clear off nicely against “all cops are bad”. There are all kinds of variations on this theme, I’m not speaking to anyone’s politics in particular… But there are people out there who have said both those things unironically, and the spectrum of opinion goes from there.

In this case, the positions are “we have an overincarceration problem” or “the system is designed against minority defendants” or some other kind of general discontentment with how strict law enforcement is. The position I think needs reconciliation is “we should do more to convict and punish rapists”.

Don’t get me wrong, I see the points from both sides, as a Canadian looking into America, your incarceration rates and the conditions of your prisons really bothers me. I have all kinds of sympathies for a general take of the former. But as to the latter, I’m not sure what you’re looking to do, particularly as whatever you do will have ripple effects throughout the system because charges of rape do not exist in a vacuum. I also wonder if the group has considered the ramifications to the accused from the perspectives of means and demographics: Black people are absolutely disproportionately represented as accused parties in violent crime. I can’t imagine a situation where this would not carry through to rape. Does that matter?

1.) Almost no one is saying “private individuals should not hold guns” or “only cops should have guns”. Aside from certain particularly deadly rifles designed for use in war (which I don’t think cops should be carrying either), I just want guns regulated – only owned by people who actually know how to use them, and will store them safely. I want guns kept out of the hands of people with demonstrable histories of violence, including domestic violence and ties to terrorist organization and the like.

2.) No, it isn’t “facially inconsistent” anyway. The fact that there are so many guns out there is a major reason why the police “fear for their lives” excuse is so effective. Those few who do want guns eliminated probably also want a system like in England, where most cops don’t carry guns.

3.) But, in any case, how would having a gun be of any use against a bad cop? I’d just wind up dead or in jail for the rest of my life. Now, maybe if you’re Cliven Bundy you can get some protection. But, marginalized people don’t have that privledge. If left-leaning protesters did what the Bundy’s did they’d be dead or in jail.

The fact that we have an overincarceration problem for some people and some offenses (eg. low level drug offenses, poor people, people of color…people the law binds but does not protect) does not contradict the idea that some categories of offense/offender are not taken seriously enough (eg. rape, murders committed by police officers, white collar crime – people the law protects but does not bind).

This was also already discussed in this thread @30ff., with mention of restorative justice as an alternative to incarceration.

Kate @ 39

“Almost no one” admits that some are, and like I said, the spectrum goes from there. I think a more common example might be people who said “what government tyranny” as a response to 2A activists who say that the 2A wasn’t meant for hunting, and then complain about government tyranny in the forms of aggressive over-policing.

And as to your third point… Deterrence? The ability to protect yourself even if it’s ultimately futile? Optics? The thing is, I used that example because I think that in the wake of the George Floyd murder “the left” as a very general body has already done that reconciliation and the gun control narrative lost. This might be temporary, the pendulum might swing, but gun sales are at an all time high, gun ownership among minorities is disproportionately rising, and we don’t hear about shootings on the media like we used to despite murder rates and shootings being higher in the last two years than they’ve been in the ten previous to that. And when murders and shootings do make it to the news, the conversation isn’t about gun control. When is the last time a Democrat pushed a gun control measure?

It’s interesting as an idea, but I’m not sure how effective it would be. And while that might be an ideal system, it doesn’t exist in most jurisdictions. When you said “people the law protects but does not bind” there is a mirror to that, the people who are bound but not protected.

Functionally, in the time between when we biased the system in favor of victims and when we installed a system of restorative justice, functionally and disproportionately, you would be locking up black men. And if we never installed a system of restorative justice, that would just be the norm.

And maybe I’m wrong, or a pessimist, or just dumb, but I can’t see a restorative justice system rocking America’s mainstream in the next decade, but America seems really bloody good at locking people up when it puts it’s mind to it.

“Almost no one” means it is a position so fringe, so outside of the mainstream, as to be not worthy of dicussion.

Against a govenment with weapons like drones that can target and blow up your house without you ever even knowing you’re a target? If your guns appear to be acting as a deterrent against the U.S. government, it is because you are actually on the same side as law enforecement. People on the left and members of marginalized communities can be summerily executed by the police for shooting members of the Proud Boys (possibly in self defense), or looking at a police officer disrespectfully.

On the state level, they are quite common. Federally, March 2021.

Corso, what is your proposal for improving the way the US judicial system responds to rape in a way that 1) is politically certain to “rock American’s mainstream” in the near future, and 2) won’t maintain the status quo of Black men being more likely to be convicted than white men, all else held equal?

Expulsion is governed by the same standard of evidence as civil cases. Ending a contract (e.g. the contract between student and college that allows someone to attend a school) is a normal use of civil proceedings. There is no way in which expulsion is an order of magnitude more severe than what can be covered under civil proceedings. If we were discussing anything other than sexual assault, I find it hard to believe that you would be making these ridiculous claims, but perhaps you truly do believe that people should only be expelled from college as the result of a criminal trial.

And you explicitly tie your concern with expulsion on the mere basis of the standard of evidence normal for civil proceedings to the fact that we are discussing sexual assault allegations (bolded in the quote above).

So, yes, your argument is gross, and your condescending pretense that you didn’t say what you said is ridiculous bullshit. I’m not sure why I ever bothering engaging with you, since you routinely pull this sort of bullshit. Good day, sir.

” perhaps you truly do believe that people should only be expelled from college as the result of a criminal trial.”

I doubt Corso would advocate people who commit academic plagiarism should be allowed to remain without a criminal trial. And academic plagiarism is far, far less wrong than sexual harassment of even the “mildest” kind. (And as a former university teacher, believe me, I am no fan of plagiarists).

Amp @ 42

I don’t have one, that’s my point.

My position is to support the victims as if they were victims and treat the accused as if they were innocent, at least until better information comes out, I called that Shroedingering earlier. That’s my position because if the victim is a victim, they need support, and if the accused is innocent, they need our support. Again: It is better, not good, but better, for 100 guilty people to go free than to punish a single innocent person, because there is no greater injustice.

Look, the reason I pointed out that black men would be disproportionately effected by changes that made it easier to prosecute alleged rapes is because they would. Perhaps because black people tend to commit more violent crime on average (something I attribute to poverty and not race), perhaps because black people generally don’t have the means to defend themselves, on average, to the same extent that white people do, on average. On the former, maybe that disparate outcome has a tinge of justice to it, because perhaps more rapists would be in jail. On the latter, it means that more innocent black men would be in jail.

And if someone wants to remove protections under the law to make the prosecution of crimes, any crime, easier, that’s something they have to contend with. Removing protections under the law disproportionately effects the people who need protecting the most. And that scales down, if the maximum punishment is expulsion, I think the reasonable expectation is that this would mean that black students would be disproportionately expelled.

Görkem @ 44

Obviously not, police wouldn’t investigate plagiarism as a crime. Also, the proof for plagiarism is pretty clear and obvious.

Perhaps my position isn’t consistent. I’m considering it. But there is a level of absurdity in “you were tried and acquitted of this act in a court of law, so we can’t prove that you did this thing, but we think that on balance, it is slightly more likely than not, so we’re going to expel you, leave you with some amount of student debt, cripple your ability to get into another school and sewer your life trajectory.”

This conversation seems to function on the assumption that the accused is guilty. And while that’s usually true, some aren’t. Imagine a case where the accused is innocent. Put yourself in their shoes. I’d imagine that whatever benefits their expulsion has societally will be exceptionally cold comfort when faced with their new reality.

And what blows me away is that for almost any other class of crime, I’d generally expect progressives to agree with me. If this empathy puts me squarely in the position that is the fourth panel of this comic, then maybe I’m OK with that.

That position is somewhat absurd. But it has very little to do with the discussion here, since we’re not talking about people who are tried and acquitted in a court of law. For most of them, if they ever get to a court of law, it will be months after the events that they are accused of.

You also seem to be working under the assumption that “schools” refers to higher education, and not to, say, middle schools or high schools.

But most importantly, you seem to be taking the standard of “preponderance of evidence” as equal to “it’s slightly more likely than not”. Which is not what it is.

So let me ask you – is there *any* standard of evidence for rape, sexual assault or sexual harassment that you’d take as sufficient for a school to expel a student over? Or do you take the fact that police can investigate these things as crimes mean that the school cannot intervene regardless of the amount of evidence?

(Also, as a side note, and speaking as someone who is currently on his institution’s plagiarism panel – the evidence for plagiarism is clear and obvious for some cases, but it’s often not, especially when a student copies another student’s work rather than published work).

1) I agree with you that a reform like making “restorative justice” is not something the American public will be getting behind in the next decade. If you’d asked thirty years ago, I would have said that same sex marriage isn’t something the American public would get behind within ten years, either.

A solution that’s in easier reach, that would get the support of the public in the next ten years, would of course be better (at least in the short term). But since you just admitted there is no such solution, it’s absurd to dismiss reforms that will be harder to reach because they’re not easy to reach.

2) I 100% agree with you that longer sentences for rapists are not the solution. (For one thing, there’s some evidence that harsher sentences make convictions less likely, and that lesser but more sure punishments are better deterrents than greater but less likely punishments.)

3) :

What did you think of OJ Simpson being sued in civil court for damages (and being ordered to pay tens of millions of dollars to the families of his alleged victims) after he had already been found “not guilty” in a criminal court?

I’m fine with it. Because there’s a reason that criminal courts require a higher level of certainty than civil courts. OJ got a very large benefit from being found “not guilty” – it is because of that verdict that he is a free man, rather than serving a life sentence in prison. But that shouldn’t free him of civil liability for what he did, or make it absurd that civil courts require only “preponderance of the evidence,” rather than “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Would you advocate that it should have been illegal to sue OJ in civil court after he got his “not guilty” in criminal court?

How about corporations? It’s very common for corporations to be sued in civil court for harms caused by activities that are in theory criminal in nature (that is, if you could prove that executives knew about and approved of those activities, they could in theory be found guilty in criminal courts). This is done partly to get victims recompense, but also because it’s more difficult for corporations to defend themselves in civil cases. Would you make it illegal for people to sue corporations in civil court if there’s a possible criminal case that could be made instead?

No one here is “operating on the assumption that the accused is guilty.” We are operating on the assumption that having different required levels of certainty for different kinds of judgements, and different levels of potential punishment, makes sense.

This distinction isn’t some weird new feminist notion; it’s something that’s foundational to how the US court systems (and most Western court systems) work. The Supreme Court’s earliest reference to “beyond a reasonable doubt” was in 1880, but note that they specified that beyond a reasonable doubt is required “in a criminal case,” not all cases. “A balance of proof is not sufficient. A juror in a criminal case ought not to condemn unless the evidence excludes from his mind all reasonable doubt.” (One of the questions was whether or not it was necessary to have a witness who was present at the wedding in order to convict a bigamist.)

There is no rational way in which saying “different venues with different levels of potential consequence for the accused should have different required levels of certainty” means the same thing as “all accused are guilty.” Can you acknowledge that these two things do not mean the same thing?

4) Forget plagiarism, then. How about punching a professor? Should that be punishable by the school, do you think, or should they have to hold off until if and when the student is convicted of assault in a criminal court?

I’m not dismissing restorative justice as a practice, but I am saying that it’s not widely in use. Until it is, the reality of the situation asserts itself: If you remove accused’s rights in rape cases you will, in practice, be convicting more innocent people, and disproportionately convicting black people, who will serve average terms more than 10 years in prison.

I should have pushed harder against this when Charles said it, but it didn’t seem important to the discussion at the time: Educational tribunals aren’t civil proceedings, they just happen to use the same evidentiary standard. This is obvious when you consider that students expelled under the rules of these tribunals have successfully taken the schools to court: You can’t sue a court when you don’t like the rulings.

As to the question… There is no civil way to sue a rapist for rape, or a murderer for murder. OJ wasn’t convicted of murder when those damages were awarded, those families asserted that OJ had done things that caused them damages, and a jury awarded the families those damages. To take a different view of it: If a person slides on ice and hits someone’s home, and the homeowner dies, the motorist isn’t guilty of murder, probably not even manslaughter, but he might be civilly liable for all kinds of things. So no… I would not preclude a civil case. Americans can civilly sue each other for whatever the courts will give them. (Although I think this is another area ripe for reform).

For clarity: I absolutely acknowledge that “different levels of potential consequence for the accused should have different standards of certainty” does not mean the same thing as “all accused are guilty”.

I said that “This conversation seems to function on the assumption that the accused is guilty”, and I said that because if we don’t have that assumption then logically we’re accepting that we’re going to be expelling some number of people who are innocent. Because while we don’t know whether or not they’re actually guilty, and even though we might not have clear evidence of wrongdoing, it’s slightly more likely than not that the accused did it and that is absolutely the definition of the Preponderance of Evidence standard.

Your mileage may vary, I suppose, but don’t think that’s right.

I think the school could probably act here… I can’t think of a situation where they wouldn’t. Mostly because I’m not sure what would need investigating. There’s always going to be more clarity outside of a rape case because it’s always an infraction to hit your professor.

But is a preponderance standard proper? If you have two students that report an assault from the other and both say “they hit me, I didn’t hit them.” There are no witnesses, no video, no medical records, no history of violence with either, but one student’s eye is slightly puffy, is that actually enough to expel? Or perhaps it was only one student that reported the assault, but there was no puffiness? I don’t know what you do with that. It seems right to separate them. Maybe shuffle some classes around so they don’t have to see each other. Move someone to a different dorm?

“Preponderence of the evidence” doesn’t mean some mechanical operation of addition: it means that the trier of fact (such as a jury, or a judge) thought that their verdict was more likely than not. So if it’s a “he said, she said” situation, the question would be who was deemed to be more credible.

But yes, “preponderence of the evidence” standard would not be appropriate here. You wouldn’t get in a car if you thought that it was merely *more likely than not* to have working brakes and a university shouldn’t allow someone on campus if they think they are just *more likely than not* to not be a rapist. Where they should draw the line I don’t know, but certainly if they’re aware of a credible threat.

“Also, the proof for plagiarism is pretty clear and obvious.”

Mmmm, not necessarily so. Sometimes it is obvious, just as sexual assault is sometimes obvious. But there are plenty of cases where it is likely but doesn’t meet the standard that would be applied in a court (if plagiarism were a criminal matter).

“if we don’t have that assumption then logically we’re accepting that we’re going to be expelling some number of people who are innocent”

Realistically, any administrative decision of any kind is going to sometimes make mistakes, and sometimes bring negative consequences on people who would not, in an ideal world, suffer them. This is true of all kinds of administrative decisions that universities make. But it’s only on this specific matter, that of expelling people for rape, that this standard of justice – 100% avoidance of any erroneous decision, ever – is applied.

I mean I hate to hark back on plagiarism, but I am sure that there have been cases where people have been expelled for plagiarism who did not actually plagiarise, they were just unfortunate enough to look like they did, on a balance of probabilities. This is obviously sad for them, but nobody would claim that the solution was for universities to stop caring about plagiarism.

“Mostly because I’m not sure what would need investigating.”

Well, if I hit my professor in private, when nobody else is around, then deny I hit him, and then refuse to accept any consequences for my actions that do not result from a criminal prosecution, and assist on continuing to attend my professor’s classes, and if he refuses to meet with me for one-on-one office hours claim that my human rights are being breached.

Thanks!

Yes, we will be punishing (and in some cases even expelling) some number of people who are innocent. I “accept” that in the sense that I acknowledge it is true; I don’t “accept” it in the sense of thinking it’s the best imaginable outcome. AS Gorkem said, this is an inevitable result of any administrative process that can punish students.

The same can be said for having a criminal justice system, which – no matter how good it is – will inevitably sometimes convict and punish innocent people.

I don’t think that any of this means colleges shouldn’t be able to punish students, or that criminal justice systems shouldn’t exist or be able to penalize people found guilty.

I certainly would agree that there should be some protections in place to make the innocent being punished less likely. But the only way to make it absolutely impossible for an innocent student to be punished, would be for the college to refuse to punish students, ever. Which seems to be what you’re advocating, but only for rape, not for any other infraction at all. (If I understand what you’re advocating, which perhaps I do not.)

I don’t really see the relevance of your argument here.

Of course a civil proceeding and a college investigation aren’t identical. But the principle we’re advocating is the same, either with a civil case or a college investigation – the venue with the less extreme and punishing possible outcome, can reasonably use a lesser standard of certainty in their decision-making.

(And by the way, you can’t sue the court, but you can appeal the decision to a higher court.)

They had to prove “wrongful death” – which means that the plaintiffs had to prove “the defendant’s intentional and unlawful conduct resulted in the victims’ deaths.”

No, that’s not the same as being legally found guilty of murder. Just as a college investigation finding a study is responsible for a sexual assault is not the same as being legally found guilty of rape. It is because these things are not the same, that it’s appropriate that they require different thresholds of proof.

It’s obviously not true that there will always be more clarity. What if the professor hit first, and the student was defending herself? Or (as Gorkem pointed out) we can imagine a he said/he said assault case. (You imagined one yourself, in your comment).

But also, that you’re agreeing that schools should be able to investigate and punish in an assault case at all totally contradicts with the principles you suggested earlier:

So when we’re talking about rape, then it’s awful for colleges to ever punish students, because criminal courts should have “sole responsibility” and are “the highest authority applicable.” But when we’re talking about assault, suddenly that all flies out the window.