If you like these cartoons blah blah blah you know the drill. Support my Patreon!

Qualified immunity is even more ridiculous than what’s in this comic strip.

Chad Reese and Patrick Jaicomo succinctly explained “qualified immunity” in the Washington Post:

Qualified immunity is a legal doctrine that shields all government workers — not just police — by default from federal constitutional lawsuits. Here’s how it works: If your constitutional rights are violated, the government workers who violated them cannot be sued (the “immunity” part) unless you can point to an earlier court case in your area holding that nearly identical conduct was unconstitutional (the “qualified” part). That means that government agents can knowingly and intentionally violate your rights, and you cannot sue them, thanks to qualified immunity.

Over time, courts have made the requirement for a precedent with nearly identical facts narrower and narrower. For instance, in the case about siccing a police dog on a suspect who had surrendered and was sitting with his hands up, it seemed there actually was a precedent with almost identical facts. But, as law professor Joanna Schwartz writes, “the hairsplitting… reaches absurd levels.”

Nashville police officers released their dog on Alexander Baxter, a burglary suspect, who had surrendered and was sitting with his hands raised. A prior decision in the 6th Circuit had held that officers violated the Fourth Amendment when they released a police dog on a suspect who had surrendered by lying down. But the appeals court ruled that this precedent did not “clearly establish” that it was unconstitutional to release a police dog on a surrendering suspect sitting with his arms raised.

Sonia Sotomayor, in a dissent, summed it up.

[The Court’s ruling on qualified immunity] tells officers that they can shoot first and think later, and it tells the public that palpably unreasonable conduct will go unpunished. [The Court is] effectively treating qualified immunity as an absolute shield.

So many real-life qualified immunity cases are already so ludicrous that there’s no need to exaggerate them for a comic strip; I just had to find a way to frame the cases. The hardest part of writing this strip was trying to find a way to fit a description of each case into the tiny space I allotted for the captions. (I could have given myself more space, but many readers start skimming when faced with large blocks of text).

I had a lot of fun drawing Earl Warren, the Supreme Court justice who wrote the first qualified immunity decision. It’s very relaxing to draw a caricature when it doesn’t matter at all if the cartoon is actually a good resemblance. But I really had a blast drawing that German shepherd. I should have stopped cross-hatching much earlier than I did, but I was enjoying myself too much.

One odd thing about doing comic strips critical of the police: I’ve gotten so much better at drawing cop uniforms.

TRANSCRIPT OF COMIC

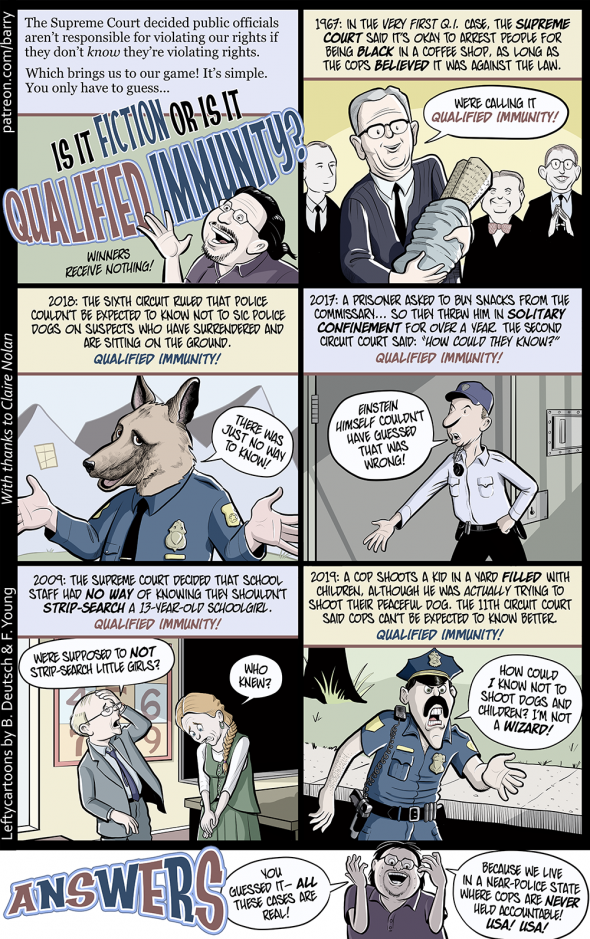

This comic has seven panels. The first six panels are squarish, arranged in a two across three down grid; the final panel goes all the way across the bottom.

PANEL 1

This panel shows Barry (the cartoonist) speaking overly cheerfully to the readers, and gesturing towards the very large letters of the title.

At the top of the panel is some introductory text.

TEXT: The Supreme Court decided public officials aren’t responsible for violating our rights if they don’t know they’re violating rights.

TEXT: Which brings us to our game! It’s simple. You only have to guess…

Very large title lettering: IS IT FICTION OR IS IT QUALIFIED IMMUNITY?

BARRY (smaller letters): Winners get nothing.

PANEL 2

A white man in judicial robes speaks directly to the viewer. He’s got wide eyes and is smiling, like he’s a proud father just after a baby is born. Behind him, three other white male judges look on. The front white man is holding a scroll with writing on it; but it’s swaddled in cloth, and the man is holding it as if it’s a baby.

CAPTION: 1967: In the very first Q.I. case, the Supreme Court said it’s okay to arrest people for being black in a coffee shop, as long as the cops believed it was against the law.

JUDGE: We’re calling it

Qualified Immunity!

Note: In this panel, and in all the following panels, the words “qualified immunity” are always on their own line, and alternate between being all red and all blue. These are the same colors used in the title lettering.

PANEL 3

A police officer, in a uniform shirt (clack tie, badges, etc) smiles and shrugs as they talk to the readers. But they have a dog’s head instead of a human head – the head of a big German shepherd.

CAPTION: 2018: The sixth circuit ruled that police couldn’t be expected to know not to sic police dogs on suspects who have surrendered and are sitting on the ground.

Qualified Immunity!

POLICE DOG: There was just no way to know!

PANEL 4

This panels shows a man in a prison guard uniform, including a billed cap and a shoulder-mounted walkie talkie, talking to someone off-panel. He looks annoyed. Behind him is a cell door, which is solid (rather than having bars) and has a small metal panel that can be opened on this side.

CAPTION: 2017: A prisoner asked to buy snacks from the commissary… so they threw him in solitary confinement for over a year. The second circuit court said: “how could they know?”

Qualified Immunity!

GUARD: Einstein himself couldn’t have guessed that was wrong!

PANEL 5

A couple of school staff types – a balding man with half-moon glasses, wearing a jacket and tie (a stereotypical principal) and a younger woman with read hair in a thick braid, are talking to each other. The man is slapping his forehead, and the woman is looking down at the floor.

CAPTION: 2009: The Supreme Court decided that school staff had no way of knowing they shouldn’t strip-search a 13-year-old schoolgirl.

Qualified Immunity!

PRINCIPAL: We’re supposed to NOT strip-search little girls?

TEACHER: Who knew?

PANEL 6

A man in short-sleeved police uniform, and with a thick mustache, angrily talks to the reader. Behind him we can see a sidewalk, grass, a bit of a tree; it looks a little suburban.

CAPTION: 2019: A cop shoots a kid in a yard filled with children, although he was actually trying to shoot their peaceful dog. The 11th circuit court said cops can’t be expected to know better.

Qualified Immunity!

COP: How could I know not to shoot dogs and children? I’m not a wizard!

PANEL 7

This is a full-width panel at the bottom of the strip. The panel contains a caption in large, friendly letters: ANSWERS

Barry the cartoonist is back, talking to the reader, grinning too wide yet looking distressed, sweating.

BARRY: You guessed it— all these cases are real!

BARRY: Because we live in a near-police state where cops are never held accountable! USA! USA!

> “I should have stopped cross-hatching [that German shepherd] much earlier than I did”

Bullshit! That sympathetic dog image is your best artwork in ages. I’d give it an “A” in an otherwise “C+” at best cartoon. Obviously, you understand the eternal innocence of dumb animals pressed into service for a human police force that you despise, and whose daily existential threats to life and livelihood you have no desire to consider.

Love the rendition of Amy Covid Barrett!

Simple twist of words …

Police dogs are indoctrinated from pup-hood to be police. You could say they are Assigned Cop At Birth.

And Qualified Immunity was created by activist judges legislating from the bench, so Republicans’ support for QI is another example of how Republicans are hypocrites.

Huh. I’d have thought this one was relatively non-controversial. Then again, I’d have thought some of the examples of police violence like the murder of Eric Garner would be relatively non-controversial. Any group, no matter how wonderful, contains some percentage of horrible people. The murder of Eric Garner is, on its face, terrifyingly unacceptable. I’d expect the debate to begin at deciding what that means, and how to proceed. It always surprises me when “no, it’s not terrifyingly unacceptable” is the starting point.

Mandolin @ 4

Relatively. There are issues that the right and left agree with generally, even if not entirely or exactly when it comes to specifics. If pressed, I’d offer the most lukewarm defense possible of Qualified Immunity, because I can see some situations where it would be a good idea to have, but my ideal system would be a whole lot more narrow than it is even up here in Canada. The other issue that comes to mind that I think most people agree on (if they’re aware of it) is Civil Asset Forfeiture, which is a blight.

“…Civil Asset Forfeiture, which is a blight.”

That’s been on my “topics I wish I’d think of an idea about” for a while.

Qualified Immunity is one of those places were lefty opinion and libertarian opinion overlap (asset forfeiture is another).

Ignorance of the law excuses not!

…unless you are a law enforcement officer of public official, in which case, ignorance excuses everything.

For some reason, the second part is not usually rendered in lofty Latin.

You missed out on one of the most absurd aspects of qualified immunity doctrine!

It used to be that Qualified Immunity was like “every dog gets one bite.” If police violate the Constitution in a particular way, well, it’s all good. But now there’s precedent! So you better not do it again…

But recently, the Supreme Court has said that courts should ordinarily consider the qualified immunity question *first* and *need not* reach the substantive question if they conclude the case can be resolved on qualified immunity grounds.

According to this study,

Not only is this allowed. It’s prefered!

My experience in reading what would commonly be called “conservative” bloggers and commenters is that dumping QI is non-controversial. It is well recognized that it is an invention of the courts, not the legislatures. Personally, to a certain extent I’d say you need it – after all, if courts and lawyers can differ on the law you can’t expect cops to know in every case how they are going to rule. But that would have to be quite narrow; given that the police’s job is to enforce the law they should be reasonably familiar with it.

That same group of people has civil forfeiture is pretty high on their list of “things to get rid of” – at least if it’s done prior to conviction and exhaustion of appeals, and even then only concerning property used in committing a crime or or purchased with the proceeds thereof. An example of someone busted for possession of less than an ounce of weed followed by the seizure of the SUV he was driving in at the time is often held up as an egregious example.

I disagree, because that’s not how we treat other professionals. I’m a lawyer, and, while I do Continuing Legal Education and had to pass an ethics test to become a lawyer, I haven’t read every single ethics and malpractice opinion out there. And yet, if I screw up, my clients can sue me. I try not to screw up and to have a good relationship with my clients. But that’s why I have malpractice insurance.

Some context:

Consider 1) who should bear the cost when government agents behave sub-optimally and private parties get hurt, and 2) who should DECIDE who should bear the cost?

Who should bear the cost when government agents behave sub-optimally and private parties get hurt?

I see three general options regarding who should bear the cost when government agents behave sub-optimally and private parties get hurt:

A. The public employee who behaved sub-optimally should bear responsibility solely.

B. Under the doctrine of respondeat superior, the principal (employer/government) should bear the costs caused by his agent (employee). But absent behavior that cannot possibly fall within “the scope of her employment,” the employee would be answerable only to her employer. If the employer wants to encourage the employee to pursue certain actions on behalf of the employer, the employer may adopt a policy that refrains from seeking indemnification from the employee. (For example, if your city wants cops to be willing to intervene in emergency domestic abuse cases, even though cops believe these cases to be rife with potential for violence, then the city may adopt a policy saying that they won’t sue the cops for acting sub-optimally, even if the conduct results in the city getting sued.)

C. The injured private party should bear the cost.

I kinda like B. I don’t expect government to act perfectly. Any human system will err. But those who benefit from the system—that is, society in general—should compensate those who are harmed by the system.

The typical argument for qualified immunity pertains to reducing an employee’s disincentive to act in risky situations, and to shield the employee from vexatious litigation. Note that qualified immunity applies only to the employee, not the government.

Who should DECIDE who should bear the cost?

Regarding the second issue, questions about who have a claim on the public purse are questions of policy, which are typically entrusted to legislatures. The general rule is that governments can’t be sued unless they agree to make themselves liable for suits; for example, the 11th Amendment bars federal courts from making states liable in private lawsuits. In other words, the default position is C: Injured private parties bear the burdens of their injuries.

However, frequently government DOES agree to make itself liable. Thus Congress adopted the Federal Tort Claims Act, and various state legislatures have adopted their own versions.

Does this liability trump qualified immunity? Only if the governments say so. Wikipedia sez that legislatures in Colorado, Connecticut, New Mexico, and New York City have either ended qualified immunity altogether or limited its application. But in general, there is no organized lobby of people who might someday be harmed by a government agent, so you can guess the outcome….

Other examples of immunity.

Amp’s cartoon identifies a number of people harmed by government agents. But consider a more mundane example: Incarcerated people who have their convictions reversed. Some states offer meagre compensation; others say, “Oops, my bad. Have a nice life.” This strikes me as a wildly unjust policy.

While most utilities are private, most operate under broad government regulation. When utility service goes out, it’s entirely foreseeable that people may die as a result; for example, roughly 1000 Texans died during a cold snap last February when utility service failed. Yet in most jurisdictions the regulated utility is not liable; harmed parties bear the cost on their own. Why? Arguably, If a utility had to bear the consequential damages, the utility would have to raise rates to cover the costs—and regulators care more about the DEFINITE consequences for ratepayers than about the HYPOTHETICAL consequences. (Consider: Pacific Gas & Electric has been held liable for wildfires caused by its system; in effect, PG&E is insuring private parties against the harm arising from its operations. Perhaps not coincidentally, PG&E’s rates are roughly 80% higher than the national average.)

In short, shit happens. Since we can’t live in a shitless world, I find it entirely reasonable that people who benefit from government (presumably that’s everyone) should compensate those who get shit on by government. But that’s my POLICY preference. Legislatures are supposed to implement those; courts are supposed to implement the laws passed by legislatures. Ergo, while doubtless some courts have made some head-scratching decisions, the true villains are the legislatures.

nobody.really @11 – I actually agree with a lot of what you say. But the problem is, the as Schroeder points out, B is not how we treat other employees in other domains.

Imagine that you owed $100 to the IRS, and an IRS employee was tasked with getting it from you. They then happened to see you walk down the street, so they pulled out a gun, told you to give them $100, and took it and deposited in the IRS account, and closed your debt. Would you accept that they should just be held accountable to their bosses, and not charged with mugging? After all, they are a government agent who did exactly what they were told to do in the line of their duties. They just chose an illegal way to do it.

Also, who gets to decide what is “the scope of [someone]’s employment”? Lets say that I worked for a state senator as one of their (publically funded) office staff as a general aide. They discover that another government worker has embezzled state funds and will continue to do so. They therefore instruct me to assassinate the embezzler. Is committing murder within “the scope of my employment?”. There’s an argument that it strictly is – I’ve been ordered to do so by my boss, and I’m doing so for the benefit of the state which employs me. Should I go ahead and follow my instructions, and then only my boss will be prosecuted for telling me to do it?

Those are both extreme examples of places where your logic fails. We expect public servants to be able to do their job, but we expect them to follow the law while they do it. If they follow the law, but people get hurt because of incompetence or malice on behalf of the government, then your logic applies. But that’s not carte blanche for individuals in government to ignore the law in pursuit of their duties. Qualified immunity, to a significant degree, is.

Interesting hypotheticals.

Just to clarify: As far as I know, qualified immunity does not prohibit anyone getting prosecuted for a crime. It only shields public employees from getting sued by private parties (presumably for money–although it would also bar suit for nominal damages).

Also, I expect a court would determine what conduct is or is not within the scope of employment. The mere fact that a superior tells you to do something would not necessarily put it within the scope of employment. (Although, come to think of it, pretty much every job description short of CEO includes “other duties as assigned.” Hmmm….) We encounter some tricky situations involving religious employers (see Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru), but I don’t expect this dynamic would arise in the context of government employment.

Nevertheless, you raise a valid concern generally: Qualified immunity reduces the disincentive for employees to push the limits of their scope of employment, and therefore reduces the disincentive for employers to ask/demand that employees do so. A study of police homicides of unarmed drivers at traffic stops revealed that many small municipalities finance themselves on traffic stops, and may pressure their officers to make them even under borderline cases.

For example, a federal study of Ferguson, Missouri (where a police officer killed the unarmed Michael Brown, resulting in days of rioting) revealed that this dynamic was rife among the postage-stamp-sized communities in St. Louis County. This is paranoid libertarian dystopia, documented in black and white–with a smattering of Hispanic and Asian.

As I argued above, the remedy should come from legislatures. But since the City of Ferguson had a financial incentive to keep the system in place, the remedy had to come from the state government. Oh, wait, the Republican-controlled state government would never side with people of color against the police–and so sat on their hands. So it fell to the US Justice Dept to sue Ferguson, and Ferguson eventually capitulated and entered into a consent decree. So much for legislative remedies.

@nobody.really

I just can’t help pointing out here that the legislature did just this and then the Supreme Court made up the doctrine of qualified immunity out of whole cloth.

42 U.S.C. 1983 provides:

Section 1983 does not contain one word indicating that Congress intended to permit qualified immunity, but the Supreme Court just made it up anyway reasoning that surely the legislature couldn’t mean what it said. So, the legislature did impose your policy preference and the Court nullified it.

Also, your question about “who should bear the cost” is missing one possibility: Insurance companies. If we got rid of qualified immunity, police officers (like lawyers, doctors, etc.) would have to buy liability insurance and insurance companies would suddenly have a strong incentive to prevent police misconduct. That would be great! I’m insured through the Texas Lawyers’ Insurance Exchange, and they make me take CLEs to make me a more competent lawyer and incentivize good behavior by partially refunding premiums if they don’t have to pay out many claims.

Good points.

Of course, saying that insurance companies bear the cost is just an indirect way to say that those who pay the insurance premiums bear the cost. In my imagination, this means government or the public employee. Is there another option?

Ironically or not, while the 11th Amendment shields states from suit unless they consent to be sued, courts recognize a variety of behaviors as indicating that the state has granted such consent–including the behavior of buying insurance.

Aside from all this policy talk, I’ll toss in belated praise for the cartoon’s form. So often, Amp’s cartoons have a theatrical quality for me: I HEAR the voices of the characters–and quite distinct voices for each character–when I read them. (This was especially true of the Mirka series.)

And, ok, maybe I’ve had too much coffee and too little sleep. But, even so, Amp’s cartoons are pretty entertaining.

Aw, thanks! :-D

Schroeder4213:

Other professionals have a choice that they can take the time to consider before they take on a specific task. For example, in your instance you as a lawyer can decide whether or not to take a case or can ask someone else’s advice before proceeding. A cop doesn’t have that luxury; the situation, often critical, is upon him or her and the officer has to deal with it on the spot. Generally at far more personal risk than other professionals.

Being a police officer is riskier than being a lawyer – or a cartoonist – but it’s not nearly as risky as some people suggest.

For comparison’s sake:

Logging workers

Fatal injury rate: 111 per 100,000 workers

Roofers

Fatal injury rate: 41 per 100,000 workers

Garbage collectors

Fatal injury rate: 34 per 100,000 workers

Delivery drivers

Fatal injury rate: 27 per 100,000 workers

22. Police officers

Fatal injury rate: 14 per 100,000 workers

To give you a sense of how dangerous 14 per 100,000 is, it’s in the same general range as any American’s chances of dying in a car accident each year (11 per 100000). It might be a little higher or a little lower, depending on what state you live in. (Ron, you may be relieved to know that Illinois is among the least dangerous states for dying in a car accident. Wyoming is the most dangerous, and New York is the safest.)

It’s notable that in many of the most controversial cases, the urgency is created by the cop. For example, in the case of Tamir Rice, the cop claimed that he had only a split-second to act, but it was their own decision to speed up to feet away from Rice and jump out of the car before it had even finished braking that created that situation.

In the case of this cartoon, neither the coffee shop case or the siccing-a-dog-on-a-surrendered-suspect case required split-section decisions to be made. Neither did the two non-cop cases in the cartoon. In the case in the sixth panel, the criminal they were chasing had already been caught and handcuffed, and they’d made everyone in the yard (six children, one adult) lie down on the ground. Then, according to the court that found in officer Vicker’s favor:

Even if you call that a split-second decision, that doesn’t magically make trying to shoot a nonthreatening dog twice in a yard full of children, either out of unwarranted panic or just for the fun of it, reasonable. (Except to the 11th circuit court, I guess.)

True. And you can add the killing of Laquan McDonald to that. But that’s what makes them controversial, after all. Well, that and in the latter case a) the fellow cops on the scene proceeded to file false reports to cover it up and b) Mayor Rahm Emmanuel (whose previous job was as then-Pres. Obama’s Chief of Staff) delayed release of a video of the shooting until after he was safely re-elected. Which is why we now have Mayor Lori “Big Dick” Lightfoot in office.

But I don’t see how the fact that there are some cops who have made decisions too quickly negates my point. Schoeder4219 was equating the decision making process in cops job to those of doctors and lawyers. I was pointing out what I believe to be a critical difference. That has nothing to do with defending their role in the particular examples you pointed out.

As far as comparing the injury rates among various jobs, I point out that when someone gets injured in those other jobs it’s generally because they did their job poorly, didn’t follow safety rules or that there was an equipment malfunction. Whereas it’s part of a cop’s job to seek out and involve themselves in a dangerous situation, not to avoid it.

Thank all that is good in Mom’s apple pie that there were no criminals in the most recent Republican regime!