Help me make more cartoons by robbing a bank and pledging all the money to my Patreon!

A couple of studies have found that conservative students are more likely than liberal students to say that they’ve self-censored on campus – although both liberal and conservative students say that they’ve self-censored.

What does this mean? It’s hard to say. For one thing, not all self-censorship is bad; everyone self-censors at one time or another. If I decide not to bring up a political argument in a statistics class because it would be off-topic when we’re talking about Bernoulli distributions, that’s self-censorship, but it might be the right choice.

An environment where no one ever self-censors would be like Twitter. That’s not ideal.

But – even if some self-censorship is appropriate – what about the finding that conservative students are more likely to self-censor than liberal students?

Some of that is probably reality-based, in that students are more likely to be left- than right-wing, and so people are more likely to push back on conservative than on liberal opinions. I’m sure that this does deter some conservative students from speaking their opinions freely. (I know liberals who have worked or lived in highly conservative environments, and they also are choosey about when they share their opinions.)

Furthermore, let’s face it – some student lefties are dogmatic and harsh when dealing with disagreement, and that could deter speech also. (This isn’t at all unique to student lefties – dogmatics and harsh people are found in any political group.)

But although that’s real, it’s also vastly exaggerated. The vast majority of students, both left and right, aren’t evil or malicious or looking to attack other students.

And much of the fear simply isn’t based in reality at all.

As Jeffrey Sachs points out, conservative students are far more likely to worry that their professors will give them lower grades due to their political opinions – but the fear is baseless.

…fully 21 percent of students who say they’ve self-censored in the classroom report doing so because they fear receiving a lower grade from their professor. And, again, conservatives are much more likely than liberals to report this fear….

This fear is clearly real. It does not, however, have any basis in reality. According to all the available evidence, faculty do not give conservatives lower grades than liberals for equivalent work.

Researchers have tackled this issue from a couple of angles. In one experiment, students were asked to compose two essays, one on the Democratic Party (its values, goals, etc.) and the other on the Republican Party. These were then given to a mix of Democratic and Republican teaching assistants for grading. The students were told that the essays were voluntary and their identities would be kept secret, giving them no reason to self-censor. The result? Neither the partisan affiliations of the students nor of the teaching assistants made any difference in how the essays were graded.

So if it’s not based on reality, then where are conservative students learning that leftist professors are ready to punish them for being conservatives?

I think a lot of it is that conservatives (and their anti-woke “centrist” allies) have been working overtime to create a moral panic about free speech on campus. For example, Charlie Kirk – a conservative with 1.7 million Twitter followers – tweeted:

I get countless of messages from students who say professors are lowering their grades & penalizing them for being conservative

Leftists dominating higher education represent a grave threat to our country & culture.

Conservative students shouldn’t be targeted for disagreeing.

Kirk is the founder of Turning Point USA, a right-wing organization that specializes in reaching out to conservative students. And he’s far from the only major right-winger who has been telling conservative students that they should be afraid. For example, then-President Trump said:

Under the guise of speech codes and safe spaces and trigger warnings, these universities have tried to restrict free thought, impose total conformity and shutdown the voices of great young Americans.

Frankly, it would be weird if the enormous right-wing media panic about intolerance of conservative students didn’t make conservative students afraid. (Just as watching violence on TV makes people more afraid of violent crime.) But this is an aspect of conservative student fear I almost never see discussed.

On an impulse, when I was drawing this one, I decided to go for a deliberately cruder and (even) less realistic character design than my usual. I would like to say that there was some deep thematic reason for making that choice, but really, I just thought it might be fun to draw ridiculously huge eyeballs.

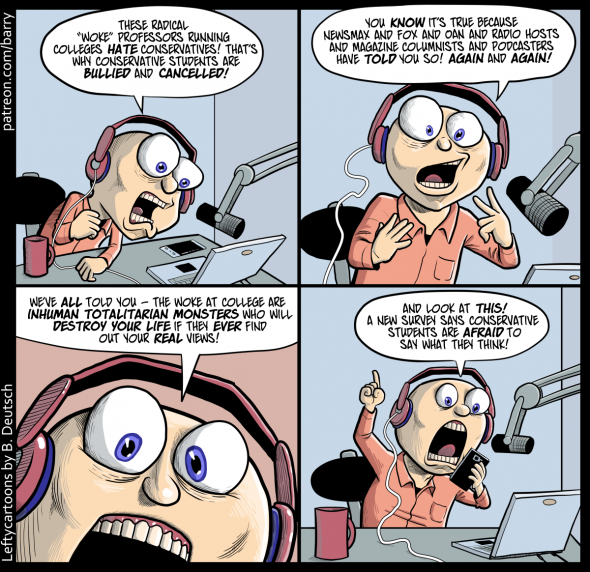

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

This cartoon has four panels. All the panels show the same thing: A man in an orange button-up shirt, seated at a table. There’s a laptop, a cell phone, and a coffee mug on the table. He’s wearing big headphones, and a professional-looking microphone suspended on a metal arm is pointed towards his mouth. In other words, he’s a podcaster.

In all four panels, the man appears to be yelling loudly, and is drawn with huge, popping eyes.

PANEL 1

MAN: These radical “woke” professors running colleges hate conservatives! That’s why conservative students are bullied and cancelled!

PANEL 2

MAN: You know it’s true because Newsmax and Fox and OAN and radio hosts and magazine columnists and podcasters have told you so! Again and again!

PANEL 3

Although the other panels all show the man in medium shot, this panel is such an extreme close-up that his entire head doesn’t even fit in panel; he’s cut off mid-mouth.

MAN: We’ve all told you — the woke at college are inhuman totalitarian monsters who will destroy your life if they ever find out your real views!

PANEL 4

The man has picked up his cell phone and is looking at its screen as he speaks.

MAN: And look at this! A new survey says conservative students are afraid to say what they think!

I don’t have a WaPo subscription, or I’d look myself…. Is there a link associated with that? I’m kind of curious on what kind of methodology they’d use to try to show something like that. If not, is anyone aware of a study that gave that result? I didn’t spend scads of time on it, but I tried to find one and came up blank.

The methodology of one of the studies is described in my post (quoted from the WaPo).

And here’s an alternative link to the WaPo article.

Thanks!

What would you say to this, then?

There’s a significant spread between those two numbers. OTOH, two out of 5 students on campus actually being reluctant to speak out is a pretty big number and seems indicative to me of an issue.

The example you give is one of what seems to be an experiment done in isolation. I would not take a group of TAs grading papers from people they didn’t know and that they know will be passed on to some 3rd party as representative of how they would grade those same papers from students whose views they are at least possibly acquainted with due to multiple contacts during classes and recitations and while they were on their own campus and within their own department.

This impinges indirectly on this topic but I would be interested in your reaction:

Ron @4: I’d say “consider the source.” The heterodox academy is not exactly unbiased.

Also @5: It’s hard to tell exactly what’s going on there since the source appears to be an unreliable narrator, but the person whose first amendment rights are supposedly being stepped on has been ordered to stop harassing one person. I see no evidence that she is not free to continue to preach to anyone else on campus. She simply is not allowed to continue to send harassing texts and making rude remarks to one specific person. How is this a first amendment crisis?

@Dianne: Didn’t you hear, the first amendment protects the rights of conservatives to do whatever they want including harassing people outside their place of work. But progressives who criticise conservative figures making public speeches need to be silenced, because their criticism is somehow an infringement on conservative rights.

Dianne asks:

According to the article:

“The university issued the no-contact orders without giving DeJong the chance to defend herself, without telling her of the allegations against her, and without identifying any policy or rule that DeJong violated,”

How can a no-contact order be legitimately issued under those conditions? Also, if a person is not told what her or she said that constituted what the program director claimed were “microaggressions” and which you classify as rude remarks and harassing texts (without having read them, so how do you know they were?), how can the person who is the subject of the order know what constituted such remarks and thus what they may or may not say that would cause someone else to file a similar report? That will chill her future speech – which does indeed constitute a First Amendment violation. Indeed, she was also told she could not participate in group texts, which is a direct suppression of her speech. It’s my guess that their inability to legitimately defend this is why the school quickly dropped the orders when threatened with a lawsuit.

So who isn’t? Surely the Heterodox Academy is committed to presenting a particular viewpoint, but that doesn’t mean that the survey is invalid. Unlike many other organizations they have released their full methodology, crosstabs and data sets, so you can judge for yourself if their commitment to presenting a particular point of view corrupted their survey.

Ron, I agree that everyone has a bias, but some places are more mired in that than others. Here’s a well-done survey (article about the survey, and the sixty-page report), in which the group of academics that ran the survey were picked to include both conservatives and liberals; I’m sure they’re not entirely bias-free, but I’d expect them to be less biased than Heterodox Academy.

O.K., but that does not tell me what’s flawed about the Heterodox Academy-sponsored survey. They are open about their methods, data set and analysis. Where’s the fault?

Only if the government is the one preventing her from speaking and even then it’s not clear to me that preventing someone from speaking in a specific venue is actually a first amendment violation. I can’t stand up in the middle of a congressional hearing and scream “Rand Paul is an intentionally ignorant twat” over and over without having security show up and escort me out, for example. In any case, a university, even a public university, is not the government. One could argue that it violates her right to confront her accuser and seek redress in a court, but again, not the government, so probably not going to fly.

If they really didn’t give the person accused any explanation or chance to tell her side of the story, it was unjust, but still not a first amendment issue.

On a very quick first look, the problems that occur to me include small sample (1000 people representing all college students?) and leading questions.

Diane, are you sure it was 1000? The report said it was 1,495.

In either case, I don’t think it’s that small a sample. For example, pollsters often use sample sizes of about a thousand to survey the entire country, with an 3 point margin of error.

Ron, on a first look, I have to admit, it’s a better survey than I expected it to be. I don’t think it’s a badly done survey, but I also don’t think it goes into depth as well as the survey I linked. (It’s way better than some others I’ve seen, though.)

My issue is more about how I’ve seen this survey reported and discussed, then it is with the survey itself. For instance, the report finds that the large majority of students would not seek any official reprisals if another student said something they found offensive. To its credit, the report said “Negative consequences for speaking out about controversial topics might be more imagined than real,” which fits in well with my cartoon. But I only found that out by reading the report; it doesn’t seem to be something that people discussing this study typically mention.

More generally, I think that people use this study, and similar ones (like FIRE’s), to draw very broad conclusions based on subjective and unclear questions.

Finally – and this is a problem that a lot of surveys have – it has the problem of giving a limited menu of choices for responses. This is an inevitable problem, but it still can produce inaccurate results or even bias because answers that aren’t listed as an option won’t be included even if they are significant. For example, when asking students why they felt reluctant to talk about a controversial opinion, they were only offered one possibility that showed concern for others (rather than concerns for what others might do to the respondent).

That one is pretty extreme – “afraid I would cause psychological damage.” I doubt I would have checked that off if I were surveyed. But if the survey had also asked if I’ve ever been reluctant to speak because I didn’t want to hurt another student’s feelings, or make them feel put on the spot, I’d definitely check that one off. If they had asked about being reluctant to speak because I didn’t want to extend a discussion that didn’t seem relevant to the class, I’d have checked that one off too. But because they’re not on the list of options, they aren’t included in results. And since nearly every item is about students being afraid of being criticized or punished, but only one item suggests reluctance to speak for benevolent reasons, that seems like it would strongly bias the survey’s results towards fear.

Another problem is that they didn’t ask students if they didn’t speak; they asked if the students ever felt “reluctance” to speak. But of course, it’s entirely possible to feel reluctant to speak, and then speak anyway. But the way this survey is talked about conflates feeling reluctance, with self-censorship.

I don’t want to sound like I’m attacking this survey’s authors. No study is ever perfect, and no study can account for everything. But I do think people are reading this study’s results to mean more than they necessarily do.

P.S. Here’s something that’s interesting: A discussion between two of the creators of this survey, and one of the survey’s critics. (Part 1, part 2).

Here’s an interesting study on this topic – interesting because it’s qualitative instead of quantitative. She ran a quantitative survey, but seemed to use it mainly as a way of identifying 16 students from various political views for the qualitative part of the study. This let her talk to them in much greater depth about what specifically they’ve experienced in classes.

(Obviously, qualitative studies can’t replace quantitative studies. But I think they can add a lot of nuance.)

“I can’t stand up in the middle of a congressional hearing and scream “Rand Paul is an intentionally ignorant twat” over and over without having security show up and escort me out”

More is the pity! I’d love to see our current laws do more to protect people doing this kind of thing, and less to protect racist/homophobic/sexist/transphobic hate speech.

My bad. I was giving an order of magnitude approximation without saying that that was what I was doing. You’re right: the actual number was 1495.

Maybe I’m being unreasonable, but I feel like the subgroup analyses are being done on some really small populations.

Really, though, I’d like to see their statistical analysis plan. They keep describing differences without saying what the p-value is on the difference or what the pretest expectation for differences is. I haven’t read the whole thing, though. It’s not unlikely that it’s somewhere in there, I just haven’t found it yet.

Also, I thought they buried the lede: One major finding is that, at least numerically, fewer people are feeling that they can’t speak out safely on campus. If that’s true then whatever is being done is more right than wrong, apparently. But I’d like to see some statistical analysis before saying whether that’s a true decrease or not.

Dianne, I agree with most everything else you’ve written here, but public universities are absolutely treated as the government when it comes to first amendment jurisprudence, and there is overwhelming precedent that public universities are bound by the first amendment when it comes to the speech of students and faculty.