The fall of Rome was caused by not enough Romans supporting my Patreon. So sad! If only there were some way of preventing our civilization from suffering the same terrible fate…

I penciled a bunch of this one during a plane ride from California. And let me tell you, I was pretty proud. No more wasting plane time reading a Jack Reacher novel for me, no sir! I was productive!

And the person sitting next to me seemed very impressed with my drawing skills, which honestly is always fun. It’s like a very slow party trick.

I had to do some other work for a few days. Then, when I returned to this strip – man, those pencils were awful! I tried to fix a bunch of figures, and then eventually gave up and redrew panels from scratch. It felt like I’d somehow forgotten how to draw.

I worked through it – although I did change the planned background (walking through a city) to a park walk, because drawing park walks is… What is that expression? It means when something is really easy and pleasurable.

But even the park came out badly the first couple of times I tried. But I kept at it, and eventually I pushed through it, and acceptable drawings were coming out of my stylus again.

It happens like that sometimes.

Then it became now, and I’m writing this text on one screen and looking at the cartoon on another screen, and it seems like every time I look at it there’s something I need to fix. It is friggin’ endless.

Seriously! Since the time I declared this cartoon done and sat down to write this text I have paused to correct:

1) Coloring the path so it’s different from the grass around it.

2) Fixing the lettering layout a bit in panel four.

3) Adding the sidebar thank you.

4) Turning the layer with the hatching lines back on because I turned it off back during correction one and forgot to turn it on.

5) Fixing his vest in panel four so it has a back panel like it does in panel one.

6) Fixing the path in panel 1 so it stops being twice as wide to the left of the boulder.

7) Coloring the plant next to the turtle in panel one, which I know I’ve done already, but I guess that change got lost at some point.

8) Color the dandelions in panel two.

9) Wait, what happened to the plant color in panel one I just did a couple of minutes ago? Why did it disappear? Aaargh. Redo that. Oh, the mushrooms lost their color too, fill that in.

10) And while I’m here anyhow, might as well color that plant on the right in panel four.

Each of these changes takes very little time to do, but it adds up and begins to feel endless. And, honestly, very few readers would notice if I hadn’t made these changes. But on some level, I think readers do appreciate the care, even if they naturally aren’t as attuned to the details as I am.

(After writing the previous paragraph, I noticed I’d drawn in clouds in panel four but not in panels one or two, and I went and fixed that).

I hope this doesn’t sound like I’m complaining. I find this kind of work extraordinarily satisfying. And it is potentially endless, in that I could keep on finding little things to fix, or add, or improve.

But at some point you just have to stop and let people see the strip.

I know in real life people seldom walk around in vests. But I really like drawing vests.

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

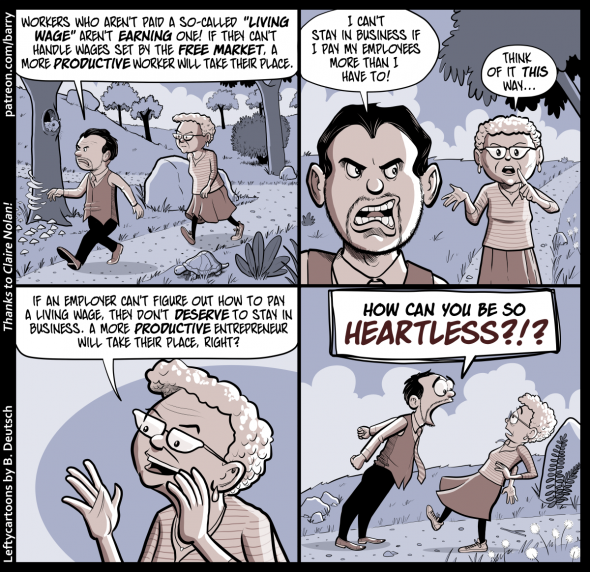

This cartoon has four panels. Each panel shows the same two people chatting as they walk through a hilly park. One, the person walking in front, is wearing a vest and tie, and has one of those beards that’s done with a very thin strip of beard. (There’s probably a word for it?) The other is an older woman, with curly white hair, a striped shirt, a calf-length skirt, and cat-eye glasses. Let’s call them VEST and SKIRT.

PANEL 1

Vest is in front, taking big strides and scowling a little as he talks. Skirt follows a few steps behind, listening with a look of concentration.

VEST: Workers who aren’t paid a so-called “living wage” aren’t earning one! If they can’t handle wages set by the free market, a more productive worker will take their place.

PANEL 2

A close-up of Vest’s face; over his shoulder, still several steps behind, we can see Skirt holding up a finger to make a point. Vest looks crabby, and honestly, Skirt looks a little crabby too. These two may not be destined to be close friends.

VEST: I can’t stay in business if I pay my employees more than I have to!

SKIRT: Think of it this way…

PANEL 3

A close-up of Skirt, who is holding up both hands at shoulder height, “talking with her hands,” and smiling as she gets into what she’s saying.

SKIRT: If an employer can’t figure out how to pay a living wage, they don’t deserve to stay in business. A more productive entrepreneur will take their place, right?

PANEL 4

For the first time in the strip, Vest has turned around to face Skirt. He looks very distressed, his eyes huge, and he’s yelling. Skirt, startled, takes a step back.

VEST: HOW CAN YOU BE SO HEARTLESS?!?

On Employers Who Can’t Afford Paying A Living Wage | Barry Deutsch on Patreon

Not necessarily. It may be that there’s (currently at least) no way to operate that particular kind of business in a fashion that will permit paying the employees a living wage while giving the employer a workable return on investment. At which point the business will simply close and no one will have any kind of job at all.

Is there a rule now that if you work for a business that goes under you can never get another job? Because I’m pretty sure that’s not how it works.

Then that particular kind of business should probably not exist. Offering non-living wage jobs to some people is not a good enough reason, especially if other viable businesses do exist.

If an industry is so unprofitable that any business that undertakes it will be unable to pay a living wage then it should either be allowed to die or, it if it necessary to society, be socialized.

@RonF: I believe Hayek had something to say to this effect

Excellent cartoon. There is probably some level of minimum wage that would shut down lots of functioning businesses, but not at the level of living wage.

Side note—a lot of the problems with living wage are really housing policy problems. The ‘living wage’ only has to look so high in some places because we’ve let housing costs get ridiculous.

I meant at that point in time. Of course that person could attempt to get another job. Although if that was the kind of job they had gotten in the first place I suspect they’re going to have a problem getting any kind of job that pays both a living wage to the employee and a reasonable return on investment to the business owner (especially if it’s a small business such that the employer has to pay themselves as well).

A fair critique. Out here in the Chicago area various corporations own dozens or hundreds of acres of land that you will commonly see a lot of people who sure look like they were born south of the US/Mexico border mowing, raking, re-planting, etc. all year. Not to mention the homes their executives live in that are getting the same treatment. My guess is that these folks are among those not being paid a living wage. My reaction to that has been “Maybe they should just let the property grow out.” My house is on 3/4 of an acre of land and if I don’t mow, rake or plant it then it doesn’t happen. I’m mostly going for the “abandoned forest preserve” look. Although I’m getting far enough along in years that one of these days I likely will have to start hiring help, or just let it all go to Hell.

Sebastian:

“We’ve let”? Who is this “we” that should have the power to tell a private property owner what they have a right to charge for the use of their property?

Caution: this comment has nothing to do with this thread but is about a re-tweet of Amp’s:

“Prison is full of people who never roller skated”

So true. A human tragedy!

Fun fact; my wife has a side hustle seasonally decorating a couple of roller rinks, one of which she spent time in as a kid. It turns out they are quite popular because the local parents can drop their kids off for an hour or two somewhere that the kids will have a lot of fun while being off the streets and out of trouble. The base decor inside looks like it hasn’t been updated since the 1970’s and that seems to suit everyone just fine. There’s a bunch of arcade games and they serve hot dogs and pizza and pop and chips and candy. They also host birthday parties. You can rent the whole place out for a couple of hours for 30 – 50 people for less than $20/head and they supply the skates.

My point being that you may think that ad is bizarre; but while it’s clearly over the top (and I think deliberately so) it would appeal to a lot of parents.

There are dozens of common regulations which have the effect of pricing poor people out of certain “nice” neighborhoods. To cite just a few examples – large minimum lot sizes, large set-backs, minimum numbers of parking spaces, and not allowing second houses on a lot.

Excellent point: Private parties might prefer to charge less, but regulation imposes costs that naturally result in higher prices.

The irony here is that we’re discussing a cartoon advocating a living wage regulation that would increase an employer’s costs, naturally resulting in higher prices—precisely the dynamic Kate finds objectionable. That is, I’d expect the employer to seek to raise prices to recover the higher operating costs resulting from paying higher wages. But in addition, I’d expect housing prices to increase. All else being equal, if salaries increase in a given location, people will tend to move there—and the resulting increase in demand for housing will tend to drive up housing prices.

It’s easy to envy people who live in high-status locations (say, in NYC or Portland) and earn high salaries (say, in finance, cartooning, or children’s theater), but the envy should be tempered with the realization that these high salaries often get transferred to the worker’s landlord. However, this dynamic isn’t unique to high-status locations. Extraction industries (e.g., gold strikes/fracking) often trigger the rise of “boom towns”/”man camps” in remote, inhospitable environments. These economies are characterized by increasing demand for labor, triggering higher wages, which attracts more workers to move to the location, triggering increasing demand for darn near everything (especially housing), triggering increasing prices. Again, the prospectors/migrant workers hope to strike it rich, but the people selling the wagon trains, pick axes, and crappy, overcrowded housing extract a large share of the earnings. I’ve read about poor cartoonists crammed into the basement of multi-tenant buildings–oh, the humanity….

More generally, to understand the challenges of “living wage” regulations, consider the consequences of setting the living wage at $1000/hr.—and then back down that wage to the point where you think those challenges disappear. But in brief, consider 1) inflation, 2) substitution effects, and 3) unemployment.

1) Inflation. A widespread increase in costs will likely result in a widespread increase in price, i.e., inflation. So even if workers receive nominally higher wages, those wages may not buy much more than before.

2) Substitution effects. Of course, imposing a livable wage regulation in one city may have little effect on the inflation rate for an entire nation. But if it DOESN’T trigger general inflation, it will trigger local inflation—that is, increasing the cost of some things relative to others. And I would expect this to trigger substitution effects.

As we’ve already discussed, minimum wage laws tend to increase labor costs for firms hiring low-wage workers—but less so for firms hiring high-wage workers. This will tend to shift business from low-wage firms (including firms operating in more depressed neighborhoods) to higher-wage firms (including firms operating in more vibrant neighborhoods). You might save a visit to the tony restaurant for a special occasion, and go to your local dive bar for a regular night out. But if the cost of the dive bar is driven up, but the tony restaurant is not, then you may shift your spending habits. That’s good for Chez La De Da, but bad for Mo’s Diner.

It’s also good for McDonald’s—because they rely on automation more than most other restaurants. More generally, as the cost of labor increases relative to the cost of automation, more labor will get automated. John Henry will continue to lose out to the steel-driving machine.

And we’d expect to see more substitution to outsourcing. Goods and services from cheaper environments (whether another city or another nation) will tend to replace locally generated goods and services.

And then, as Ron noted, some firms will simply go out of business entirely. I think many types of recycling operate at thin margins—and recyclers may be reducing the range of things they seek to recover, focusing more narrowly on higher-margin commodities such as aluminum to the exclusion of many types of plastic.

3) Unemployment. As firms go out of business, or shift to automation, or to outsourcing, we would expect to see increased unemployment—with all the usual consequences.

First, what drives an employer’s hiring decisions? One factor is efficiency—productivity for the buck. Every NBA team would like to hire someone has productive as LeBron James—but he’s expensive. At some point, firms conclude that they’d be willing to hire less productive players that are willing to work for a lower salary. (This was the idea underlying Sabremetrics analysis in MoneyBall.) The same is true throughout the wage scale. But if the law imposes a wage floor, firms will have less incentive to higher lower-productivity employees. I would expect this to leave some people unemployed—not because they can’t produce anything, but because they can’t produce at the level to justify the minimum wage. We observe relatively high labor costs in Europe–and relatively high unemployment rates.

Moreover, even sexist, racist, ablist, and look-ist employers will hire minorities they disfavor if the price is right. But if a law requires setting a wage above its market-clearing price, then the employer will receive more qualified applicants then he or she can hire—and will necessarily have to discriminate on SOME basis. If you have an inclination to hire white, able-bodied, good-looking people, and they don’t command much of a salary premium relative to other candidates, why not? I would expect this to exacerbate disparities in unemployment rates.

Unemployment doesn’t merely deprive people of income; it deprives them of a conventional social role and opportunity to develop a work history.

At this point, Amp will pull out a nifty graph showing that the federal minimum wage has lost purchasing power due to changes in inflation over time. But there have been other relevant changes, too. The 1938 federal minimum wage initially didn’t do much to depress unemployment among black people and women because it didn’t apply to agricultural workers and domestic servants—two industries that employed a disproportionate share of black people and women. These industries no longer employ such a large share of the population—and from the 1960s through 1990, federal labor laws gradually expanded their scope to encompass these jobs. This is just to say that apples-to-apples comparisons over time are hard, because many variables are at play.

ALL THAT SAID—

A) Today’s unemployment rate is weirdly low; I don’t get it. You will probably have noticed a resurgence of union activity. Maybe this reflects the power of having a Democrat in the White House—but I suspect not. Rather, it reflects the ratio of labor supply and labor demand. In short, unions achieve their greatest success precisely when they are least needed because normal supply-and-demand dynamics would tend to improve wages/hours/working conditions anyway. Nevertheless, the moral is this: I don’t know what I’m talking about right now–though at least I KNOW that I don’t know, so there’s that.

B) As a matter of public finance, if we AS A SOCIETY want people with less income to have more income, then we AS A SOCIETY should pay for it—and not foist the burdens onto one segment of the employer market who deign to hire low-income people. Let’s just raise the necessary revenues using normal, progressive taxes, and then allocate them as we deem appropriate. To be clear, increasing taxes and government transfers will ALSO create market distortion such as substitution effects—but I suspect they create less distortion.

Clearly we need a remedial policy of installing roller skating rinks in prisons. Though the roller derbies could get testy….

Nobody.really – I don’t object to regulations that result in higher costs, if they are for the greater common good. For example, well-designed fire codes probably save millions of dollars in fire damages and thousands of lives every year.

As for your rant on the damaging effects of raising the minimum wage, you don’t provide any links to actual evidence. Moreover, all your assertions have at least two common flaws. They presume that most employers are paying their employees as much as they reasonably can based on what those employees produce. That is incorrect. They pay people as little as they can get away with. Most businesses can afford to pay more without raising prices. It also presumes that they charge as little as possible to make a modest profit. This is also false. They charge as much as they can get away with, often taking in enormous profits.

There is some anecdotal evidence that raising wages doesn’t raise prices–or affect the business’ bottom line.

for example“>

Somewhat related:

In 2019 California passed California Assembly Bill 5—commonly referred to as AB5—requiring employers to treat various gig workers (“independent contractors”) as employees. Vox published an article praising this development.

Vox then promptly canceled its relationship with (“laid off”) 200-ish independent contractors in California, replacing them with about 20 full- and part-time employees.

In this instance, AB5 seems similar to a lottery: It leaves a few people richer, and most people poorer (a “reverse-Robin-Hood” effect). But unlike AB5, people can choose whether or not to participate in lotteries.

Perhaps you could argue that the benefits of these labor policies exceed their costs. But I don’t see how you would deny that these policies HAVE costs.

(H/t Kevin Corcoran)

AB5 emerged out of the obviously ridiculous inflexibility of Dynamex, and multiple industries, including the California arms of media companies like Vox, urged legislators to include carve-outs for workers, like freelance journalists, whose professional advancement and financial survival depend on the kind of contractual and one-off work Dynamex blanket bans. Vox itself published an article advocating for this exception and namechecked the assemblywoman who introduced the bill. They quoted her as acknowledging the danger AB5 poses to its own content producers and editors, and making vague mouthnoises about getting round to changing the language and expanding the exemptions.

Omitting that crucial bit of history makes Vox look hypocritical, sure, but nobody can say Vox and other interested parties didn’t lobby California lawmakers to avoid these outcomes. Exemptions were made under AB5 for roughly 100 professions and journalists and photojournalists were not among them; the ceiling remains at 35 submissions.

Your comment is technically correct – “Vox Media” does own “SB Nation blog,” where the freelancers were cut. And it also owns “Vox.com.”

But while you didn’t actually lie, imo your comment was (perhaps unintentionally) deceptive because it leaves out relevant info. “Vox.com” is (iirc) editorially independent from its parent company, not an official voice of Vox Media’s policies or leadership, and it’s run by different people than the people who run “SB Nation,” where the sort-of layoffs you’re talking about took place.

Did Nobody realize this when your comment was written?

We’ve absolutely deformed the housing markets by not letting people build denser housing and more housing. This intentional under supply of housing has caused prices to inappropriately rise. To your point about private property, we should upzone and let lots of people make money building lots of new housing.

According to Krugman:

From one of the pieces Krugman linked:

Why $15 minimum wage is pretty safe

The interview with David Card, linked to in the paragraph above is particularly good. On his work on the mimimum wage:

Nope, nobody didn’t know nuthin’ about the ownership structures of Vox Media.

Nor did nobody know about the Dynamex decision, which provides a useful context for understanding AB5; hat tip to Saurs. Indeed, I’ve seen a variety of discussions about AB5, yet somehow never encountered this analysis before.

Nevertheless, the points about the benefits AND costs of intervening in the labor market remain.

I know it is an aside, but the AB5/Dynamex disaster strongly suggests that it would have been better for CA to act against Dynamex more forcefully under the old standards rather than destroy independent contractors with a very poorly thought out messaging bill.

This part of the case was fine ” held that workers are presumptively employees for the purpose of California’s wage orders and that the burden is on the hiring entity to establish that a worker is an independent contractor not subject to wage order protections.” but the completely new test was unnecessary. The old test could have gotten us there without upending the entire concept.

So, no one’s found evidence that the moderate increases to the minimum wage being proposed will lead to higher unemployment and/or inflation? In looking for the information I provided @18, I also found reporting on a recent study indicating that many companies are responding by cutting hours so employees don’t qualify for benefits any more. The result is that emplyees make somewhat less overall. So, when I see evidence that there are unintended consequences, I fess up.

In Australia, casual workers who don’t get benefits get the cost of benefits prorated. So, if a full time worker would get $40 in retirement contributions each week, a part time casual would get an extra $1/hour to make up for that loss (we have medicare for all, so health insurance isn’t an issue). These things are complicated.

I also admit that I think requiring companies to pay their workers enough to support themselves is a moral issue and that we should look at other ways to mitigate unintended consequences of such requirements.