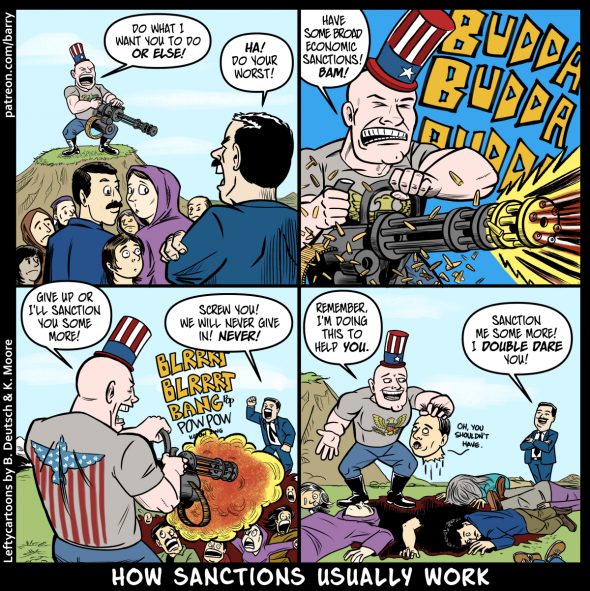

This cartoon is by me and Kevin Moore.

─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──

Kevin writes:

Any time I can draw over-the-top, absurd violence with satiric intent is fun for me. I don’t like guns or violence in real life, but in fiction it can be silly or dramatic (or both), and maybe a little cathartic. The violence of governments is harder to exaggerate, because we take so much for granted yet there is so much more than we realize. The sanctions issue is a good example: the focus of discussion and media coverage is on the will of regimes and individual leaders, but the people themselves are ignored despite their suffering. We don’t measure it and we don’t want it to complicate our good intentions.

I don’t think sanctions are absolutely necessary or unnecessary— but beyond apartheid South Africa in the 80s and possibly the BDS movement, it’s hard to think of sanctions that have been effective. Russia does not seem deterred in its war against Ukraine, no matter how many sanctions the west imposes. Iran may have felt pressure by sanctions to join the treaty with the US under Obama, but after Trump scrapped it, I doubt they’ll bend to that kind of pressure again— not so long as the US can’t be trusted to hold up it’s end of the deal. Nonetheless our foreign policy will continue to rely on sanctions, because elites are oblivious (as always) and they don’t want to lose any tools they have.

I love the energy of Kevin’s cartooning here (panel two is my favorite). And I never could have drawn that gun so well!

I should mention that the funniest thing in this comic strip – the decapitated head saying “oh you shouldn’t have” – was made up by Kevin.

─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──

Professor Francisco Rodríguez, in his paper “The Human Consequences of Economic Sanctions,” writes:

The evidence surveyed in this paper shows that economic sanctions are associated with declines in living standards and severely impact the most vulnerable groups in target countries. It is hard to think of other cases of policy interventions that continue to be pursued despite the accumulation of a similar array of evidence of their adverse effects on vulnerable populations. This is perhaps even more surprising in light of the extremely spotty record of economic sanctions in terms of achieving their intended objectives of inducing changes in the conduct of targeted states.

And blogger Daniel Larison writes:

Sanctions advocates often present using this weapon as a peaceful alternative to war rather than acknowledging that it is a different form of warfare, and they do this to make an indiscriminate and cruel policy seem humane by comparison. The illusion that economic warfare is a humane option makes it much easier for politicians and policymakers to endorse it, and the fact that the costs are borne by people in the targeted country makes it politically safe for them to support.

Unfortunately, sanctions seem to be an everlasting, untouchable policy in the U.S., supported by elites of both major parties. But we have to hope for change, and sheesh is this post a bummer.

─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──

When I posted this cartoon on Patreon, I was taken aback to be accused of supporting Russia in Ukraine.

But being anti-Putin – to be clear, I loathe Putin & his government – doesn’t obligate me to support ineffective and inhumane policies.

The U.S. has imposed sanctions on over 20 countries since 1998; studies have shown that sanctions are ineffective at creating regime change (and are in fact counterproductive), and harm the worst-off people in the targeted countries, not the rich and powerful.

─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

This cartoon has four panels. Each of the panels shows an Uncle Sam type figure – actually just a really muscular bald guy wearing a tight t-shirt and a tall stovepipe hat, decorated in an American flag motif. The t-shirt has an eagle design, similar to the eagle design on the official Great Seal of the U.S.A., on front, and a eagle-plus-stars-and-bars design on the back. Sam is holding what Kevin described to me as “a mashup of different hand held Gatling guns I found on a google image search. I went with what looked the most ridiculous.”

Uncle Sam is standing on a small hill. Across a field from the hill, Sam is facing a wealthy-looking man in a suit. The wealthy guy has well-cut black hair and a large mustache.

On the field between Sam and the Mustache dude is a crowd of ordinary citizens, men, women, and children.

PANEL 1

Sam, standing on the hill, is yelling at Mustache Dude. The people standing between Sam and Mustache Dude look around nervously.

SAM: Do what I want you to do OR ELSE!

MUSTACHE: Ha! Do your worst!

PANEL 2

A closer shot of Sam, macho scowl in place, as he points his gatling gun and blasts it. There are lots of ejected bullet casings flying through the air and a huge sound effect that says “BUDDA BUDDA BUDDA.”

SAM: Have some broad economic sanctions! BAM!

PANEL 3

A shot from behind Sam; he is continuing to fire the gun. We can see a bit of the terrified crowd between Sam and Mustache Dude. Mustache Dude is shaking a fist in the air and yelling back at Sam.

SAM: Give up or I’ll sanction you some more!

MUSTACHE: Screw you! We will never give in! NEVER!

PANEL 4

Sam is standing in the field, smiling, surrounded by bleeding corpses. Sam is holding up a decapitated head, smiling at it as he talks to it. In the background, we can see Mustache Dude across the field, completely unhurt, grinning with his arms folded.

SAM: Remember, I’m doing this to help YOU.

DECAPITATED HEAD (small): oh you shouldn’t have.

MUSTACHE: Sanction me some more! I DOUBLE DARE you!

LARGE CAPTION PRINTED ALONG THE BOTTOM OF THE CARTOON: How Sanctions Usually Work.

─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ── ─── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ──

You’re on a roll with these comics!

Thanks! :-)

BS. The sanctions have totally caused issues to orc war efforts in Ukraine like they don’t have enough truck tyres.

Also the majority of the orcs support the war with all of its atrocities.

They deserve what’s coming.

The cartoon isn’t visible to me. I’m using Chrome.

I take your point, though.

Honest question: What would you propose instead? (Alternate universes are hard and non-falsifiable, but to me it seems plausible that, in one where we didn’t sanction Putin, he’s already won the war in Ukraine and moved on to imposing immense human suffering in other soon-to-be-former Democracies.)

ETA: Just to clarify, I see the problems you raise, so I don’t mean my question as a “gotcha.” I am *extremely* open to a solution that would reduce human suffering relative to sanctions. I’m just not convinced that “doing nothing” does.

Schroeder @5: Targeted economic sanctions?

Hmm, I guess I’m out of my depth already. I’m not sure if more targeted sanctions would work sufficiently as a deterrent. (And many of them are targeted)

To some extent, even Putin probably relies on public support for the war, and I wonder if broad sanctions are more effective at diminishing that. That said, their effectiveness to that end is probably dampened by Putin’s complete control of Russian media.

But sure; good answer. I did miss the word “broad” in Amp’s cartoon, and I guess that’s probably crucial to the point he’s making.

Unfortunately, one megalomaniac (Putin) has created a no-win situation for the world.

I can see the cartoon now.

As for Russia, the purpose of sanctions is weakening their capacity for war much more than trying to get regime change, and I think they’re working for the first purpose.

On the other hand, sanctions in general don’t work and they make life harder for a lot of people.

I’m curious about your evidence that sanctions in general don’t work. So far, Russia (1) has not defeated Ukraine and (2) has not invaded any other countries. I realize that’s not strong evidence (it’s hard to say what would have happened if we didn’t sanction Russia, and correlation does not imply causation), but it’s certainly *consistent with* sanctions working.

Iran? North Korea?

I should look for a more complete list, but those are at least starting points.

Schroeder: For an overview of the evidence that sanctions generally don’t work, read the “What the Academic Literature Says about Sanctions” section of this CATO paper. Sanctions have a terrible record of working. (I know nearly everyone here is left wing enough to be suspicious of CATO, as am I. I could link to other overviews coming to similar conclusions, but I chose CATO’s overview because it’s footnoted.)

The conclusions of the literature aren’t unanimous, but the weight of the evidence is that sanctions are usually not effective.

Looked at in more detail, it seems like sanctions are most likely to work when 1) they have a narrow goal, such as “release this prisoner,” or 2) when they’re used against democracies. In contrast, they can actually make a dictatorship more entrenched.

I’d mainly propose three things:

1) Narrow embargos of specific sectors, i.e., arms embargos.

2) In the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, supporting Ukraine’s side of the war more directly in various ways other than sanctions, such as diplomatic support and providing them with arms.

3) Accepting that the U.S. is not omnipotent, and that there are limits to our power to control what happens. It’s important to support Ukraine, but we shouldn’t assume we can make things turn out like we want them to, and we shouldn’t support ineffective policies that are cruel to non-elite Russians.

@Amp: You are writing this as if sanctions are purely an American idea dreamt up out of American naivete and universalism. But in the most relevant current case, that of Russia, they are not, quite the opposite. The Ukrainians themselves, independent of any American internal dialogue – the Ukrainians being the actual suffering party- are directly, clearly and actively asking for sanctions. Should we tell them “We know better than you how to defend your homes”? Doesnõt the principle of supporting the victim apply very clearly here? The Ukrainians say sanctions matter, and they are the ones who are actually being affected here.

Judging by the Saddam-ish look of the dictator in the comic, I assumed this comic was more about sanctions against Iraq or Syria than about Russia.

Avvaaa: Hypothetically, what if the Ukrainians asked the US to start bombing Russian schools and hospitals – does the “principle of supporting the victim” obligate us to do so?

(To be clear, the Ukrainians haven’t asked for that. But if they did).

You’re right, this cartoon wasn’t intended to be about Russia and Ukraine in particular. But people have responded to it by talking about that (understandably).

@Amerpersand,

Thanks! On Cato, while I am to their left generally, I think they do good work on areas of overlap, like (especially) immigration. For instance, I thought this was excellent: https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/why-legal-immigration-nearly-impossible.

@Ampersand: I feel like your question is not that insightful. It is very easy to make “support the victim” seem ridiculous by saying “what if the victim asked for something horrifying and ridiculous?” Victims do not ask for this.

Supporting the victim is about realising that, when the victim asks for things that do not seem to make sense for us, it may be a matter of our perspective being incomplete because we are not the victim, not the victim being “wrong” and needing to have their requests filtered through our superior, privileged (we are not being invaded) worldview.

It is worth noting that many times, the victims do not support sanctions, or support very limited sanctions (e.g. most Cuban opposition groups want the embargo lifted).

You mention a “narrow” embargo of “specific” sectors, and you mention the Russian arms industry. But the Russian arms industry is a major part of the Russian economy, employing between 2.5 and 3 million people. Even a relatively small contraction of that industry as a result of sanctions would result in job losses, which seems to fit your definition of “cruelty” to “non-elite” Russians, since the people losing their jobs would not be executives and senior managers but technicians, specialists and line workers, and they would suffer, as would their children, spouses and other dependents.

Your final statement about how the USA needs to recognise it is not omnipotent is an interesting one. I am sure we all agree that the USA is not omnipotent – even the most ra-ra American exceptionalists wouldn´t outright say they think the USA is omnipotent. This feels like a bit of a strawman, to be honest.

The USA may not be omnipotent, but it is very powerful, and it seems like it is being called on to utilise that power in a situation that is about as morally clear cut as these things can possibly be. I am not sure where your hesitancy comes from. Yes it is a shame that non-elite Russians get caught in the flack when the Russian economy takes a hit (to say nothing of the non-elite Russian conscripted soldiers being killed by American weapons), but I don´t think there is a way to fight a war that really preserves them – and if one goes too far down this road one arrives at the Ben Garrison pacifist point of view where the Ukrainians should surrender to “end the bloodshed”.

The U.S. is not omnipotent, but somehow whenever things like this happen the rest of the world looks to us to provide the solution. Which I’m really tired of, as it gets us involved in things we need to stay out of. One good thing (in my opinion) that Trump did was to hold NATO’s feet to the fire and bring much higher visibility to the fact that most of the member nations were not keeping their military funding commitments. The Ukraine war has, I think, finally gotten many European nations that do not share a border with Russia to finally wake up and realize that Putin wants to reassemble the

Russian empireU.S.S.R. and is not above using force to do so. The Poles figured this out a long time ago.It has always seemed to me that a subtext behind sanctions was “If we put the squeeze to a nation hard enough maybe the populace will revolt and get rid of their current regime.” But that never happens, especially given that one of the first things that an authoritarian regime does is disarm the public.

And with regards to the Cato study; that’s a good explanation of how difficult it is to legally immigrate and then gain citizenship in the U.S. I’ve known a few people who’ve done it, but then I work in a highly technical field where it’s easier (not easy, but easier) for people to do so. But then, so what? Why shouldn’t it be difficult for people to immigrate into and become citizens of the U.S.? Immigration law’s purpose is to benefit the U.S., not immigrants.

The obvious answer to this is that making it extremely difficult for people to immigrate into the U.S. does not benefit the U.S.

That depends on who you make it extremely difficult for.

The article discusses 5 different ways to qualify for immigration to the U.S. I won’t quote their numbers, just my opinion on them:

The refugee program: This is a valid point; qualified refugees (and poverty or lack of economic opportunity in their home nation != “qualified”) should be processed a lot more quickly than they are now. The author states “only a few nationalities are even considered” but doesn’t say what those are or why.

The diversity lottery: This program should not exist. I see no particular reason why someone should be favored for immigration just because there aren’t a lot of immigrants from that country in the U.S. already.

Family sponsorship: This program should not exist. You chose to come here knowing you were leaving your family behind.

Employment‐based self‐sponsorship: IIRC this is for people who have unique skills or abilities, or can invest a lot of money. The former is the kind of person we should give priority to. The latter sounds like someone buying a spot into the U.S., but if they have the potential of employing a lot of people and actually do so within a certain period of time it might be a good thing to do.

Employer sponsorship: Again, if these are people with certain skills that cannot be found within the current American population (and not just “cannot be found to work for what we want to pay them”) then by all means bring them in. The author decries “these restrictions exclude nearly all workers without college degrees”, but I’m don’t see why that’s a bad thing. Quite frankly I work for a tech company that likes to hire Indians (people from India, not Native Americans) because they work for less money than native-born Americans, so I’m sensitive to this one.

The author then lists the baseline criteria that potential immigrants must meet to be considered, centering on health, criminal history, security profile and prior immigration law violations. He has a problem with some of them. One statement he makes with regards to barring someone based on their criminal history is “Only crimes that truly threaten others should bar a person’s right to immigrate to the United States.” My take on that is that the U.S. already has plenty of people who don’t respect the law, and since there are so many people who want to immigrate who DON’T have a criminal record, why should we accept people who do?

This may be the cruelest thing I’ve seen from Ron and that’s saying something.

They chose to come here knowing that the family sponsorship program exists. If family sponsorship is eliminated – which I don’t think is a good idea – basic fairness would require an “grandfather clause” allowing those who immigrated before family sponsorship is hypothetically eliminated, to continue using family sponsorship.

Immigration is good for the US and good for Americans. Even on a purely selfish level, I want much more open immigration because it would make Americans wealthier and better off, thereby rendering then more likely to be able to afford supporting my Patreon, which in turn makes me better off and more likely to support their Patreons (or buy merchandise from their stores, etc etc).

A fair point and one I had not considered. A grandfather clause would be appropriate.

That depends on who is permitted to immigrate, and why. At no point have I ever held the position that the U.S. should not allow immigration.

Technically correct, the best kind of correct.

Not sure how we got from sanctions to immigration, but…Why not let anyone who wants to come to the US do so? Immigrants are, in general, less likely to commit crimes and more likely to pay taxes. Plus, by my MacBook Air*, they add to the country in ways that native borns don’t. What’s the downside, even if you don’t care that the people trying to enter the US are doing so because the situation in their home countries is desperate?

*Steve Jobs was the child of an immigrant. From Syria IIRC.

Took me a while to get your point Jacqueline. Let me clarify, then. I have always supported legal immigration. My issue is with people who come here illegally, or who come here legally and then violate the terms under which they were admitted to the U.S. (e.g., overstaying a student visa, failing to show up for an immigration hearing, etc.).

A position I’ve stated before, if you care to look through the history here.

RonF, this is not a meaningful statement in this context. The debate is over what types of immigration should be legal, and what types of immigration should be illegal. Most of us favor making more immigration legal; you favor making certain types of currently legal immigration, such as family sponsorship, illegal. Saying you support legal immigration but not illegal immigration is just talking around the issue rather than addressing it.

I stand by my statement that Ron is technically correct. We all know that’s the best kind of correct.

(Chris has unnecessarily, but beautifully, clarified my point)

True; and I’m interpreting “us” to be “the people who post on this blog” and nothing broader.

In the context of discussing the Cato study, yes – you are correct. I had interpreted Jaqueline’s statement as addressing a broader context than the Cato study, however. and responded on that basis.

Anyone who has entered this country legally has a right to be here as long as they observe the terms under which they entered the U.S. and that right should be protected. This applies even if I think the terms under which they entered the country should not be legal.

Anyone who has entered this country illegally or entered legally but has violated the terms under which they entered the U.S. does not have a right to be here and they are subject to removal at any time, even if I personally think that there are good reasons to allow them to stay.

Yes, I do favor eliminating some of the current programs under which people have entered legally. But that does not mean I am anti-immigration. I’m all in favor of legal immigration into this country. I believe it benefits the U.S. I think it would be of more benefit if some changes (such as those I suggested) were made to the immigration laws. Being in favor of changes to immigration law does not mean I oppose legal immigration overall.

I also think it would be of benefit to this country if the current Administration would put more resources into enforcing control over our borders with an emphasis of preventing illegal entry, adjudicating immigration/asylum cases and keeping track of people who have been permitted provisional entry into the U.S. until their cases come before a court. But enforcing immigration law and preventing illegal entry into the U.S. seems to be something that this Administration wants to de-emphasize. I believe it’s fair to say that at least half the country sees this as circumventing the law. And while plenty of people who see this as circumventing the law approve of that, the overall effect is that trust in this Administration and in the Federal government’s commitment to upholding the Constitution, the separation of powers and the rule of law vs. the rule of man is being severely damaged if not destroyed in the view of many.

Then your employer is either illegally discriminating and not providing equal pay, which is clearly illegal, or moving its work sites to India, in which case the issue has nothing to do with immigration to the US. So how are immigrants to blame?

What, buoys designed to kill, razor wire, and armed guards told to drown immigrants aren’t enough for you? What do you want then? Concentration camps? A wall similar to that which used to exist in Berlin? Oh, wait, we have those too.

Ron, if I may ask, how long has your family been in the Americas? In the US? Would your ancestors have been permitted to enter per your immigration plan?

Ron is totally for legal immigration. He just wants a lot less legality of immigration. Perhaps, judging by the things he’s written here, so much less that there is no legal way to immigrate at all.

But technically – the greatest of all words! – he’s never been against legal immigration.

Jacqueline @ 30 and Dianne @ 28

I think you’re doing that thing you do, where you take your opponent’s stated views, interpret them through this arch-conservative caricatured filter you employ, and react to what you think they really mean as opposed to what they actually said. I mean, if you want to call it a “technicality” that Ron isn’t the strawman you’ve built that vaguely resembles him, that’s fine. But even though Ron is more hawkish than I am on immigration, it’s beyond obvious, at least to me, that he doesn’t actually want to halt all immigration into America.

Which isn’t to say that I agree with Ron here. Frankly, not having considered things like people choosing to come here being aware that if they immigrate the family sponsorship program exists to bring the rest of their family over, which probably influenced their decision to apply (which would, I assume, be true for most people with a family) is such a devastating own-goal it isn’t even funny. Ron, we agree more than we disagree usually, but if you haven’t thought out your positions even that far, I’m not sure how much weight we should grant any them on the topic.

As someone who has immigrated twice to two different countries, I probably have more experience with this than most people in this community, although both times I was a minor, and my parents did the paperwork, so I’m open to being wrong about that. My impression is that North America has a weird relationship with immigration, and people seem fundamentally incapable of talking about it in meaningful ways.

For instance, that CATO paper says that legal immigration is “nearly impossible” except for in “the most extreme of circumstances” because less than 1% of people who want to immigrate are actually accepted as legal permanent residents. But a few paragraphs later, they break that down; In 2018, a Gallup survey indicated that, globally, about 750 million people wanted to immigrate (from the citation), of those, 158 million people would choose America as their top choice of destination (from the article), but administratively, 32 million people applied and just under a million achieved legal permanent residence status. I’m not sure that something can be classified “nearly impossible” when it happens a million times annually.

Regardless, what CATO did here was say that all 158 million theoretical people (because that number is an extrapolation based on a survey) that aspired to immigrate was the denominator in the equation, that the million people that were given green cards was the numerator, and came out with .6%. That’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. It’s meaningful only to activists, and then only as a rhetorical tool.

In reality, 126 million of their 158 million never applied, and while you could argue that some of them didn’t apply because they knew they wouldn’t be accepted, others would face barriers like not being able to afford travel, having a criminal record, or a myriad of easy to think of if you’re inclined to do it reasons, most of which the average person wouldn’t think of as “extreme”, and not the responsibility of America.

So the actual numbers are that 32 million people applied, 1 million were accepted, and the percentage of people who apply that legally and permanently immigrate is 3% per year (Which is where the Netflix series “3%” got the name).

But even that isn’t a particularly relevant number. That’s not how nations look at immigration. It doesn’t matter if 32 million people applied or 320 million, there were only ever going to be a million immigrants accepted. The system is aimed towards disqualifying however many applicants are needed to achieve that target number, this isn’t an exact science, I don’t think there’s a quota system in place, but with a machine as large as America’s, they’ve gotten pretty good at it: As more people apply, the criteria gets more strict. And when you think about that, it only makes sense: Immigration is supposed to benefit America, and what America needs is not determined by what people outside America want to do.

So… The meaningful question is: What’s that number? What is the target number? Because we can fight over process and qualifications on the margins until we’re blue in the face, it doesn’t really address the number.

You’re giving Ron a hell of a hard time for wanting less, while not stating your own position. Are the current numbers acceptable? Would you like to see more? How much more? Where would they go? What would that look like?

Cato thinks immigration is “nearly impossible”. Is that a problem? What’s the percentage that makes that better? 10%? 5%? 2%? What about all of them? Does anyone here think that America could take in the 158 million people who might want to immigrate? What about just the 32 million people who apply?

Ten million? Six million? Two?

Lest I be accused of the same: I think America could probably handle about 4 million as a maximum number annually. That’s proportionally about the same as Canada which has the largest immigration-population ratio on Earth, although Canada has built infrastructure up over generations to support that, and I think it would take some build up to get there. But it still matters what kind of immigrants are taken in, as Germany and France are learning the hard way, so I think there still need to be standards, and it’s possible (perhaps even desirable) that we get to a point where the number of successful applicants might not be equal to the number of theoretical “spots” to fill. It would be great to be at a point where we actually don’t fill “the number” because America just don’t need the immigration. But we’re not there, because you do.

Wir schaffen das.

The major problems that I keep hearing about in the US include:

1. Lack of people to fill all the jobs. Not just low paying jobs, either. There are not adequate numbers of people to fill the jobs in practically any part of the medical system.

2. Low birth rate. More immigrants=more people and many of them are younger, including children. Problem solved. (For us, anyway. The worldwide problem and issues of brain drain are left as an exercise for the reader.)

3. Vacant real estate. Whether its the 16 million vacant homes or the ghost office buildings, more people would mean more buildings filled and therefore fewer buildings falling apart from neglect. (Yes, there are homeless people who should be housed in some of them. I agree. But it’s not like they’re going to be if we just restrict immigration. The same people who want less immigration also prefer that people die in the streets rather than receive free or low cost housing.)

Aren’t convinced by my reasons? Fine. In that case, let’s talk about how to reduce the number of people who want to immigrate to the US. Face it, it’s not because the US is so great. It’s because their situation is desperate and they need to get out any way they can. So improving conditions throughout the world would mean fewer people trying to immigrate. Maybe stop supporting dictators and overthrowing elected governments you don’t like? In the interest of reducing immigration if you can’t manage it on humanitarian grounds?

Oh? Which of the places that I quoted Ron was it not what he actually said?

I would not at all be surprised to learn that at least in some cases my employer is illegally discriminating and not providing equal pay.

My mother’s family arrived at the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630 when the Massachusetts Bay Company was actively encouraging emigrants to go to their colony and establish farms. They continued farming within 30 miles of their initial establishment until the 1990s when my mother’s generation was dying off and her brothers sold the land for development; their descendants, my cousins, are all mostly teachers and engineers now. My father’s family emigrated from Bermuda somewhere around the 1830’s (IIRC). I am not as well informed as to what they did for a living when they arrived and afterwards.

Based on the immigration standard of admitting people who can be self-supporting and have skills that are perceived to be of value to the nation I’d say that yes, they’d have been admitted then under the rules we have now. But the needs of a colony in the 1630s and the U.S. in 1830 were very different from the U.S. now, so it’s entirely appropriate for the U.S. to have different immigration rules now than it had in 1830 or the Massachusetts Bay Company had in 1630.

True.

OTOH, now you’re putting words into my mouth I didn’t say. Let’s see you back that up by quoting where I said that.

That doesn’t seem particularly obvious to me.

This is certainly also a factor.

I certainly support the latter statement but I strongly suspect doing much about either of these things to the point that it would have a marked effect on illegal immigration is far beyond the U.S.’s resources.

I think the main attractants for emigrants is that 1) even if you stay poor when you move here you’re going to live better than the poor people in the country they came from, especially if you’re willing to work and 2) the various government bodies are far less corrupt and you’re more likely to be able to keep a larger amount of the fruits of your labor and less likely to get abused by the authorities (either physically or otherwise).

Dropping useless and harmful sanctions that are creating or adding to terrible economic conditions is free. For example:

A large proportion of the increase in refugees to the US and other countries in the last couple of years comes from three countries: Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

All three countries’ economies are being dragged down by U.S. sanctions. That’s not the only factor, of course, but it’s an important factor.

(Unsurprisingly, the most pro-sanctions politicians tend to be the ones who also say the refugee crisis is a crucial danger to Americans).

Dropping sanctions is basically free. But other strategies are affordable and (while not a cure-all) seemingly effective.

That program is currently costing $1 billion a year, but it should be more, and be expanded to more countries. Considering that the Federal budget is $4.45 trillion, the costs of programs like these are not outrageous. In particular, politicians who claim that the refugee crisis is an existential threat to the U.S. shouldn’t hesitate to spend $5 or $10 billion annually to mitigate the causes of the refugee crisis.

There’s an overview of the Biden administration’s root cause strategy here.

I’m not a general fan of sanctions; it’s a case by case thing. The biggest problem I see is that there seems to be a general idea that if we cause massive economic disruption in a country the people there will turn against their oppressors, overthrow them, and put in a nice Westminster parliamentary system or a Federal republic.

The actual outcome, however, seems to be that the oppressors now have a ready-made excuse for doing what tyrants always do, and that is to blame the people’s trouble on an outside source. Sometimes it’s been Jews, but in this case it’s us. If the public was as well armed as Americans are it might work but that’s rarely the case. Especially when the civilians who ARE armed often are being armed by warlords running drug cartels who don’t care WHO is head of the government as long as said government can be paid off for a reasonable price.