“Subprime mortgages.” Boy, I sure pick exciting topics, don’t I?

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

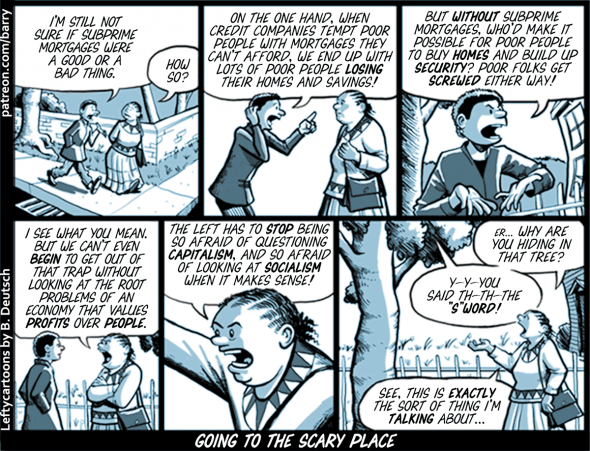

This cartoon has six panels, with a caption at bottom. The caption says “GOING TO THE SCARY PLACE.”

All the panels depict two woman, talking as they walk through a residential neighborhood, with fences and houses and trees. One woman is wearing jeans and a peacoat; the other is wearing a sweater over a long flowy skirt.

PANEL 1

PEACOAT: I’m still not sure if subprime mortgages were a good or a bad thing.

SWEATER: How so?

PANEL 2

PEACOAT: On the one hand, when credit companies tempt poor people with mortgages they can’t afford, we end up with lots of poor people losing their homes and life savings!

PANEL 3

A closeup of Peacoat. She’s looking a bit angry and making a palms-up gesture with her hands that I’d roughly translate as “what the fuck?”

PEACOAT: But without subprime mortgages, who’d make it possible for poor people to buy homes and build up security? Poor folks get screwed either way.

PANEL 4

Sweater talks seriously, her arms folded on her chest. She’s got her mouth open WAAAAY wide, and I have no idea why I drew it that way (I’m typing this transcript in 2019, and this cartoon was drawn in 2007).

SWEATER: I see what you mean. But we can’t even begin to get out of that trap without looking at the root problems of an economy that values profits over people.

PANEL 5

Close-up on Sweater. She’s getting a bit excited/angry as she talks, waving her arms and with an intense expression.

SWEATER: The left has to stop being so afraid of questioning capitalism, and so afraid of looking at socialism when it makes sense!

PANEL 6

Sweater has a questioning expression as she looks up into a tree. Peacoat can no longer be seen, and her word balloon is coming down from the tree.

SWEATER: er… Why are you hiding in that tree?

PEACOAT (speaking from tree): Y-y-you said th-th-the “S” word!

SWEATER: See, this is exactly the sort of thing I’m talking about…

Tree-hiding is appropriate in a political sense if you propose socialism rather than a socialist policy.

I don’t disagree that there are aspects of socialism that are preferable to aspects of capitalism. But when someone says “look at socialism to solve this” (as opposed to “look at ______ policy to solve this) then it seems to me that they are committing political suicide. I don’t want the left to do this.

Well, as much as I agree that that formation is a bad idea, Sailorman, I think the point is that it’s a good idea to argue vigorously for policies that work, and if those happen to be socialist policies, we shouldn’t let that bugaboo frighten us away from ‘doing good stuff’.

Well, sure. But I don’t think it’s a bugaboo we should even acknowledge. Things don’t work because they’re socialist policies, they work because they’re good policies.

Oh, I agree, and I don’t think our opinions are all that different here.

I think the reason Amp mentions socialism is because there’s virtually no circumstance where someone on the left can propose a policy that involves collectivization without being accused of marching lockstep down the road to communism . . . at which point, historically, we crumble like wet tissue paper.

The point is that we need to Not Do That.

Myca, that’s exactly what I intended!

Hey, I’m all in favor of questioning anything, and generally in favor of de-stigmatizing ideas.

That said, I don’t know what the sub-prime mortgage system says about capitalism or socialism per se. The sub-prime market includes 7.5 million first mortgages, or about 11% of all first mortgages (distinguished from second mortgages/home equity loans/lines of credit/etc.) This fact helped drive home ownership rates to a record 69%.

Is there a higher rate of delinquency and default among sub-prime lenders? Sure. Most troublesome, sub-prime adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) – and most sub-prime mortgages are ARMs – have a delinquency default rate of 11%. Put another way, for every 11 sub-prime households with ARMs that are in trouble, there are 89 households that are enjoying the benefits of home ownership that they never could have enjoyed otherwise. I don’t mean to sound indifferent to the suffering of the 11 households, but even the Bailey Building & Loan would run short of bread, wine and salt celebrating all the success stories here.

Should we prosecute fraudulent lenders? Sure. Should we have a social safety net? Sure. Should we tighten up lending regulations? Perhaps. But I’d be curious to know which socialist nations are free of fraud. Or how many socialist nations have a home ownership rate of more than 69%. (Or are we thinking “socialist” as precluding private property?)

I’d suggest health care finance as a better target for socializing. Even free-marketeers like Larry Summers have come around to this view.

I was thinking that socialism, like capitalism, is not an all-or-nothing proposition, and thus talking about ‘socialist nations’ is sort of missing the point.

In fact, in a way, that’s kind of the point of the cartoon.

—Myca

I think it’s a good cartoon. One thing missing from the discussion though, is the recognition that if there is an ideological maximalism afflicting US politics at the present, it is the maximalist ideology of Capitalism as practiced by market theocrats and corporate elites..

At the risk of seeming like a dummy, I have to admit I don’t know what “maximalism” means, W.B..

I’m trying to figure out the connection here between sub-prime mortgages and socialism.

First, just because poor people are tempted by sub-prime mortgages doesn’t mean that they actually have to get one. People are tempted all the time by stuff they can’t afford, including houses (and apartments). Also, being poor doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t know how to do math, or figure out what their income is likely to be when the rates can jump up.

I’m also not drawing the connection between short-term profits and getting a mortgage. After all, a mortgage is a pretty long-term loan.

Now, I have been hearing about how a certain number of these sub-prime loans were made by unscrupulous lenders who misrepresented the ability of the borrower to qualify for the loan. If there’s a criminal act involved the criminals should be prosecuted and should even have to make good on the loan. And if there’s an element of fraud here that has escaped the law, new legislation might be appropriate.

I’m also wondering how many of these loans were made to poor people. I have heard of homes in my area bought with these that are very expensive homes, bought by middle-class people overreaching their income.

Ron:

I’d go so far as to say that the idea that capitalism promotes obsession with short-term profits is totally unfounded. People start biotech companies with the intent of losing money for years before they ever turn a profit. Timber companies plant trees that take decades to mature. Long-range planning is ubiquitous in capitalist economies.

In fact, capitalism actually strengthens incentives to engage in long-term planning. Suppose you can make $1,000,000 by killing your golden goose now or collect $200,000 worth of golden eggs per year by letting it live. Even if you need $1,000,000 today, you don’t kill the goose. You can make a lot more money by selling it for $2.5 million (assuming an 8% market interest rate).

Insofar as people do obsess over short-term profits, this is typically a result of imperfect information and principal-agent conflicts (i.e., management misleading investors in order to boost the stock price and cash in options), neither of which is peculiar to capitalism. Find me a politician who can afford to do the right but unpopular thing for ten years before it starts to pay off, and we’ll talk.

Isn’t housing for the poor one of the few areas where this country has actually been willing to put socialist solutions into operation? What is public housing, after all, but collectivism?

I’m not suggesting any normative conclusions as to whether public housing (or subprime mortgages) is a good or a bad thing. I’m just thinking that it may not be entirely fair to say that socialist ideas on this issue have been ignored. Of course, Amp may have other socialist concepts besides public housing in mind, in which case my point goes away.

OK. The state will take possession of your house, and distribute the rooms in it in a fair way to people in your neighborhood. You can put in a request to stay in one of the rooms, but of course you’ll need to get your crap out of the common areas. Those belong to the people now.

“I’d go so far as to say that the idea that capitalism promotes obsession with short-term profits is totally unfounded. People start biotech companies with the intent of losing money for years before they ever turn a profit. Timber companies plant trees that take decades to mature. Long-range planning is ubiquitous in capitalist economies.”

Neither high tech innovation nor sustainable development would really be possible without government support and subsidy. State-funded initiatives like the Human Genome Project precede private sector utilization of the same.

That’s not to say that problems of delayed gratification are any better the more centralized the institution. The squandering of the Soviet economy with the arms race immediately comes to mind. (In a sense, nuclear missiles are built for the future, but the motivations behind building up a costly arsenal in the here and now are very similar to those behind building up an immense fortune in the quickest way possible.) To uphold the level of long term planning required to sustain a society, particularly one that has to grapple with the twin horns of continuous technological innovation and environmental sustainability, a system of both informal and formal rules have to be set so that caving in to the short term is not made a more tempting proposition than it already is. Government isn’t perfect, just as referees don’t possess all-seeing eyes, but it’s better than letting self-interested players set their own rules.

“Find me a politician who can afford to do the right but unpopular thing for ten years before it starts to pay off, and we’ll talk.”

Well, American taxpayers were asked to make economic sacrifices so that people other than them could win wars and moon races. But I do understand that mall competitive systems share many of the same pitfalls (and strengths), regardless of what we choose to call them.

“Or how many socialist nations have a home ownership rate of more than 69%.”

Does the welfare state qualify as socialism? If so, then every nation in the world that has more houses than mud huts is a socialism.

Yeah, the subprime mortgage thing is a real problem. All those poor people, dragged from wherever they were renting by jackbooted thugs and forced to look at houses they can’t afford. All those potential homeowners who had goons with truncheons standing over them, ready to beat them within inches of their lives if they went through the very basic process of working up a budget, seeing what they could afford in a house payment and either buying the house they like, buying a house they can live with and more easily afford, or putting the whole process off for a few years until their credit score looks better and they have more money saved for a downpayment (and of course, the discipline necessary to keep their credit use in check and to actually save that money during those few years was strongly frowned on by–well, by some capitalist somewhere). All those medical experiments performed on people to suppress their Delaying of Gratification Gene.

For this, we need to get the government to interfere in the market even further. Because that’s always worked so well in the past.

No risk. The fault is mine for slipping into jargon. Briefly, it’s drawn from the distinction between maximum and minimum programs. A maximalist is one who advocates a the maximum program dictated by a particular ideology or perspective. Someone who believes that Government shouldn’t regulate business while turning over all services provided by government to private interests, could be described as a maximalist for Capitalism. Such a description is even more applicable to one who argues that the market is the sole, legitimate force in determining economic priorities.

In contrast, anyone advocating the abolition of “capitalism” to the extent of collectivizing mom and pop stores and kid’s lemonade stands could be described as a maximalist on the other side.

Taking the Continental Congress as an example, John Adams was a maximalist in the cause of independence. Other delegates, not so much.

Maximalists tend to take an all or nothing view, treating any position less “ultra” than their own as an objective capitulation. We see this in US politics when any attempt at collective action to meet a social need is denounced as “Socialism”. Robert’s post above is also a useful illustration in that he attempts to equate public housing programs with Government seizure of private residences. The domination of our discourse by this kind of maximalism is also on display in the often heard denunciations of European nations as being “socialist.” For the maximalist ideologue of Capitalism, any collective economic action, other than that determined by the “market”, is by definition socialist and leads inevitably to communism.

This is why, according to such thinking, we cannot have national health care and ought to “privatize” Social Security.

W.B. Reeves:

First, part of the reason there are few maximal socialists is that maximal socialism (or something closer to it than any modern society has been to maximal capitalism) has been tried in a number of countries, and it failed miserably and tragically pretty much every time (I say “pretty much” just to hedge my bets—I’m not actually aware of a case in which it didn’t).

But maximal capitalism isn’t in favor, either. Very few people believe that everything should be privatized. For example, the vast majority of libertarians believe that there are a number of legitimate government services, such as military, police, courts, and legislation. Privatization of roads is somewhat more popular among card-carrying libertarians, but I doubt it’s something favored by more than 1% of the population. Many people believe that schools should be operated privately, but the idea that they should be funded privately (i.e., no forced subsidization for the poor) is a fringe view. Likewise medical care.

Unless you’re simply defining maximalist capitalism as whatever the “market theocrats” (cute—would that make you a government theocrat?) and corporate elite (actually, my impression is that the corporate elite tend to prefer the status quo insofar as it keeps competition in check) support, it really is a fringe ideology (note that this is not a comment on its merits).

Whereas the market has never produced negative outcomes? Government intervention is always bad? That’s as reasonable as arguing that Government intervention is always good and has never produced a bad outcome.

As for the business of putting the crises in the home loans game down to the personal failings of the consumer, it’s the old Caveat Emptor: the ingnorant and inexperienced deserved to be swindled. Very convenient for the swindlers.

It’s not wise to make a God of the Government. Neither is it wise to make a God of the market.

Brandon, You seem to be implying that maximalism is a perfectly respectable position so long as the particular ideology hasn’t been given an effective field trial. You’re entitled to that position if you want to claim it. I disagree but you’re entitled to it.

I could quibble about what constitutes an effective field trial but since I am not a maximalist it isn’t relevant. Unlike maximalists of both the left and right, I don’t see every instance of personal initiative as validating capitalism. Neither do I think that a mixed economy is the harbinger of victory for either ideological camp. Nor do I ignore the respective histories either camp.

It’s a characteristic of Maximalist thinking , as it is with all schools of ideological purity, that anything varying from the orthodox line is excluded from the “true church.” Consequently, such ideologues, barring their complete triumph, always present themselves as a remnant of the “true faith.” In this context, anything less than the privatization of “everything” is defined as a concession to the left/collectivism/socialism/communism. Nothing short of the privatization of the military, etc., counts as ideological extremism. Evidently, everything else is fair game.

This kind of intellectual box allows one to treat fundamental questions, such as the abolition of public education, as minor policy adjustments rather than the profound engines of social engineering they actually constitute.

I can’t take credit for “market theocrat”, as far as I know Eric Hobsbawm coined the term in The Age of Extremes, a book I recommend to anyone with an open mind.

I think that some sectors of the media are making sub-prime morgages out to be much worse of a problem they they really are. 89% of people with these kinds of morgages are paying them on time.

I agree that if someone signed a morgage contract and there was fraud or some other kind of illegal finaggling going on then the broker or whomever committed the illegal act should be prosecuted, but I don’t believe that everyone should be disallowed from getting a subprime morgage just because some people (whether poor or not) bit off more than they could chew.

W.B. Reeves:

I’m not. My point is that not having been empirically shown to have cataclysmic shortcomings is a necessary but not sufficient condition for respectability.

So when you say “maximalism,” you don’t really mean maximalism. You just mean the variant of capitalism advocated by those whom you’ve arbitrarily labelled as maximalists of the right.

And the examples of maximalism that you give are pretty silly. Opposing nationalization of the health care industry isn’t maximalist—it’s centrist. Maximalism in the context of health care policy would consist of opposing all government funding for medical care on the one side, or total nationalization on the other side. And I’m willing to bet that there’s a lot more support for the latter than for the former.

Likewise, there’s nothing really radical about privatizing Social Security. And most advocates of privatization still support forced saving and some government funding for care of the indigent elderly. Besides, isn’t the status quo already kind of maximalist? I’m kind of afraid to ask, but how could you make Social Security more socialist? In a quantitative sense, I guess you could make it bigger, but in a qualitative sense, it’s already 100% government-controlled.

The abolition of public education, in the only form that has any non-fringe support (i.e., vouchers), really is a minor policy adjustment. All it does is replace the current monopolistic education system with one where consumers have choice. The poor children still get education, and the rich still pay for it. Abolition of public funding for education would be a radical change, but only a handful of radical libertarians support it. The only change that would be required to make the status quo truly maximalist would be to ban private schools altogether.

And it’s kind of amusing that you cite the abolition of public schools as an example of social engineering, when public schools were originally designed to be (and remain) engines of social engineering. In fact, the social engineering aspect of public education is still cited as an argument against privatization. We can’t have school choice, opponents say, because parents might choose to send their children to schools which will teach certain unacceptable values.

But you did repeat it, and it’s nonsensical. Theocrats want to impose their religious values on others. It’s what theocracy is all about. And it’s precisely what market liberals oppose. We have nothing against socialist collectives, as long as participation is voluntary. The analogy between socialism and theocracy, on the other hand, is quite apt. Socialists have a vision of how society should work, and they seek to impose it on others, just like real theocrats.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that market liberalism is superior to socialism (it is, but not just for this reason). But it does mean that “market theocracy” is a contradiction in terms.

“W.B. Reeves:

First, part of the reason there are few maximal socialists is that maximal socialism (or something closer to it than any modern society has been to maximal capitalism) has been tried in a number of countries, and it failed miserably and tragically pretty much every time (I say “pretty much” just to hedge my bets—I’m not actually aware of a case in which it didn’t).

But maximal capitalism isn’t in favor, either. Very few people believe that everything should be privatized. For example, the vast majority of libertarians believe that there are a number of legitimate government services, such as military, police, courts, and legislation. Privatization of roads is somewhat more popular among card-carrying libertarians, but I doubt it’s something favored by more than 1% of the population. Many people believe that schools should be operated privately, but the idea that they should be funded privately (i.e., no forced subsidization for the poor) is a fringe view. Likewise medical care.”

A fair assessment, although you neglect to point that market maximalism fails not only from lack of popular support, but it being a supremely shitty idea in the first place. Consider British Rail, Argentinian water, or Californian power.

“Maximalist” capitalism just fails on the empirical record. Laissez-faire in 19th century Britain caused frequent depressions and uncertainty, laissez-faire restructuring in South America have ratcheted up poverty and inequality while producing slower rates of growth than the ‘nationalized’ 50’s and 60’s, and laissez-faire dismantling of public services in some African countries have actually caused a downturn in the literacy rate. Of course, we always have apologists explaining why such and such were imperfect representations of the whole, something that would be if anything truer of the former Communist countries. In neither case do they mean these ideas would anything short of foolish to try and implement again.

“(actually, my impression is that the corporate elite tend to prefer the status quo insofar as it keeps competition in check)”

This is indeed a persistent problem in mixed markets. Many industry regulations, particularly where fairly homogeneous products are concerned, have less to do with consumer safety than the big guys trying to make it harder for upstart competitors to get in the game. But how often is this presented as a major problem by the anti-regulation crowd? How often are they likely to target major corporations, as opposed to busybodies who wish to impose draconian measures of equality? A problem is not going to go away if no one wants to talk about it.

“Unless you’re simply defining maximalist capitalism as whatever the “market theocrats” (cute—would that make you a government theocrat?) and corporate elite (actually, my impression is that the corporate elite tend to prefer the status quo insofar as it keeps competition in check) support, it really is a fringe ideology (note that this is not a comment on its merits).”

Actually, the equivalent ‘government theocrat’ would be someone who wants the private sector eliminated completely, the way ‘market theocrat’ would be someone who wants the wholesale privatization of every government service. That someone is an assertive, passionate defender of a mixed market does not make them an extremist at the opposite end of Rothbard and von Mises. I’ll agree, though, that ‘theocrat’ is an inappropriate term in either instance.

I think the cartoon is great. But I think it would be better with one small change. The real tragedy of the Sub-prime mortgage market is not the person who bought a house with sub-prime finance and is not being foreclosed. The real tragedy is the person who owned substantial equity in a home and than used that equity as collateral on sub-prime debt. In many cases this money was reinvested into the house (solid surface counter tops anyone?) or used to pay down other debt from commercial spending.

It’s not necessary for the poor to own a house to have a place to live. While I think home ownership is usually a good thing it’s not always true. It lowers the owners mobility. It deeply invests them into the area where they bought the home. It commits them larger payments than renting (usually). It has higher transaction costs than renting, thus making it harder to get away from a house then an apartment. A house requires regular upkeep that will cost money.

I think if your future income is uncertain, if the economic future of your current area is uncertain, and if you lack the financial resources to handle a major repair (roof, furnace, sewer tie in, anything over 4k) than owning a house is a very risky proposition. It takes the existing uncertainty of the situation and magnifies the consequences of something bad happening. A house is a great place to live but not necessarily a great investment.

I’m not saying that this should be captured in a cartoon. But capitalism, as an ideology really pushes home ownership.

fwiw my solution to this would be in bankruptcy laws. Lenders would be less willing to do business with people they thought likely to default if bankruptcy laws were stronger for borrowers. I’d like to see credit card debt eliminated entirely, and house protection capped at 150% the median house price for the area code.

The Leninist, authoritarian type of socialists unwittingly proved to be plutocracy’s best friends. The Leninists’ atrocities and institutional tyranny handed the propagandists of plutocracy priceless assets. Even the working classes became frightened of socialism because they were taught to think “socialism=gulags and massacres”.

Neither high tech innovation nor sustainable development would really be possible without government support and subsidy. State-funded initiatives like the Human Genome Project precede private sector utilization of the same.

Actually, IIRC, one of the major impetuses (impeti?) for the HGP was that private companies were doing some of this work, and then owned the information. It was perceived that having the information about the human genome controlled by private hands was Not A Good Thing, and so the HGP was set up to make the information available to everyone. But the private sector was developing and using information about the human genome before the HGP was set up and running.

Frankly, Amp, I agree with the intent of the last two panels. Let me strongly encourage the American left to use the “s” word as much as possible to describe their proposals and policies.

Except, as sylphhead so ably points out, capitalism can be shown to have had “cataclysmic shortcomings”as well. A survey of the enclosure acts, slavery, the dispossession of the native american peoples, the history of European imperilialism in general and the political and military results of the great depression

would be instructive on this point.

My evident meaning was that your standard for judging what is and is not an extreme ideological position is itself an expression of such extremism.

Data please.

Again, mere assertion won’t do. The failure of Bush’s attempt at privatization argues against you.

Who said anything about making it “more socialist”? Are you responding to me, or carrying on some

internal dialogue? I’m not the one arguing for a radical alteration. You’re the one who asserts that “there’s nothing really radical about privatizing Social Security” even as you argue that the current program is “100% government-controlled”. If the privatizing of Social Security dosen’t strike you as radical, then I can’t imagine that you’d consider the nationalization of health care to be radical either.

Relatedly, you might want to reconsider this:

If you are correct that there is more support for the latter than the former, it means that the core opposition to the nationalization of health care is a minority opinion. It follows that support of some form of Government funded health care is, in fact, the centrist position. Is that your position as well?

Government creation of a tiered educational system based on the ability to pay is an extremely radical bit of social engineering. One likely to produce the sort of class divisions that have bedeviled British and European society for centuries. To deny this is to deny that price has any relation to quality. The abolition of private schools would be quite radical as well but no one is advocating that here.

Quite. Public Education, like most every public policy initiative, is an engine of social change. My point is that pretending that the abolition of public education by stages (vouchers) is not as much an effort at social engineering as was its creation is counterfactual. Junking the current system of education for an access model based on Saks vs. Wallmart would have profound consequences for generations to come. People have a right to know what the end social product they’re being sold will be. It clearly isn’t equal access to a

quality education. Social policy is always social engineering regardless of the specific instrumentality used to accomplish it. Such policies must, therefore, be judged on their general outcome. Unless, of course, one prefers a social order that institutionalizes privilege based on economic standing. Incantations to “consumer

choice”, as though it were a mystic fetish, can’t obscure this.

Terminology is not substance. There is no substantive intellectual difference between a belief in “the market” as the governing force in social relations and a belief in any other abstract, totalizing principle given the same role. Actual distinctions only emerge in the material outcomes of such belief systems. It is no accident that slavish adherence to supposedly hostile ideological systems so often results in their

adherents behaving in identical fashion.

It is nonesensical to claim that market devotees don’t have a vision of how society should work. If that were so it they would hardly be involving themselves in disputes over social, political and economic policy. The market itself is a social creation. Do you think that market adherents don’t have a vision of how the market should work? Are devotees of “the Market” simply nihilists who believe in random , chaotic impulse?

Your blanket assertion about socialists is a caricature. You again illustrate a primary trait of maximalist thinking: the reduction of an opposing perspective to a monolithic extreme by means of ignoring any contrary evidence. There are many different streams of socialist thought and as many different modes of its political expression. Behaving as though there are no distinctions to be made between the socialism of a Willy Brandt or Golda Meir and the socialism of a Castro or Hugo Chavez is absurd. You may as well equate Malthus with Adam Smith or Margaret Thatcher with Augusto Pinochet.

If you actually believe that “market liberals” never seek to impose their “values” on others, I can only refer you to the historical survey I recommended above.

BTW, isn’t the current debacle in Iraq an example of just such a failed attempt?

Passionate assertion in the absence of, or in positive opposition to evidence, is a workable definition of

faith. It is yet another characteristic of maximalists and ideologues of all stripes. It is a proclivity that you

have indulged in repeatedly here. Consequently, I find your bald assertion that market theocrat is a

contradiction in terms to be somewhat less than convincing .

I assume this is what you were refering to with your use of the invented phrase “market theocracy”.

Time was when creditors were considered to have a fiduciary responsibility not to entrap people into debt they couldn’t handle. (I don’t know if this was ever codified in law; I mean a moral responsibility.) Granted, no one should take out a loan without running the numbers and various not-so-good-case scenarios (what if I’m out of work for six months? what if a family member has a catastrophic illness? etc.), but the companies making these loans know or should know perfectly well if the prospective debtor will suddenly be homeless when the rates skyrocket; they are the ones in the money business, and you can bet that they’ve done the math. If they know they’re setting someone up for ruin and they make the loan anyway, it may or may not be legal, but it’s wrong. (Doesn’t the Bible forbid usury?)

If they know they’re setting someone up for ruin and they make the loan anyway, it may or may not be legal, but it’s wrong.

Hear, hear. It may be that, given recent history, they simply figured that the taxpayers would be put on the hook to make good on the loans.

We’ll see what happens; I’m wondering if, when these loans fail, there’ll be a hue and cry for “the government” to bail out the creditors and debtors so that they don’t go out of business/thrown out of their homes.

BTW, let me be the first to encourge the American left to use the word “socialism” to describe their proposals. By all means.

Ron:

Too late. The other RonF beat you to it. You’ll have to settle for being the second.

Ahhh, geez.

We’ll see what happens; I’m wondering if, when these loans fail, there’ll be a hue and cry for “the government” to bail out the creditors and debtors so that they don’t go out of business/thrown out of their homes.

What would you recommend? Seriously. While I’m not too keen on the use of my tax dollars to bail out debtors who should have known better (and I’d be happy to let predatory lenders sink without a trace), I can’t think of a good alternative.

To prevent future financial disasters, I would favor whatever legislation is needed to make sure that the terms and conditions of loans are spelled out clearly, in plain English and large print, to forbid predatory lending (you are not allowed to make a loan that will ruin the debtor in a couple of years unless he wins the lottery), and to circumscribe severely if not outright forbid subprime lending. I know this would lock a lot of people out of homeownership, but I’m not convinced that homeownership is an unalloyed Good Thing. I’ve seen all the studies associating homeownership with responsibility and good citizenship, but I’m not sure which way the correlation runs.

I’d also like to see that godawful bankruptcy law fixed, or at least an exemption put in for catastrophic medical bills. (Of course no one should have catastrophic medical bills in the first place, but that’s a whole other can-o-worms.)

What would you recommend?

People who take out loans they cannot pay off go bankrupt. People who make loans that don’t get paid off go bankrupt, and their investors take a loss. If people making loans committed fraud, then they are tried and convicted in criminal court and the people they defrauded go after them and the companies they worked for in civil court.

“People who take out loans they cannot pay off go bankrupt. People who make loans that don’t get paid off go bankrupt, and their investors take a loss. ”

The first part is already true. The second part (where the company making a loan that doesn’t get paid off) is highly unlikely to happen since they are able to make money on all the people who ARE paying and are paying insanely high rates, etc. People default on credit cards and bank loans all the time – and yet, credit card companies are turning incredibly high profits. Even as foreclosures and unpaid cc balances increase the banks and card companies are still getting filthy rich. So, the little guy still gets screwed no matter what, and the rich guys get richer no matter what.

The second part (where the company making a loan that doesn’t get paid off) is highly unlikely to happen since they are able to make money on all the people who ARE paying and are paying insanely high rates, etc. People default on credit cards and bank loans all the time – and yet, credit card companies are turning incredibly high profits.

Not to mention that in the case of a secured loan (such as a mortgage) the creditor ends up with the collateral and can resell it and incur little if any loss, and the debtor forfeits any equity and ends up in a deeper hole than before. These days most creditors’ business plans are explicitly based on getting people too deep in the hole to climb out, but not so deep that they throw in the towel, and the change in the bankruptcy laws makes it harder to throw in the towel. (Contrary to the propaganda that the loan industry put out, most bankruptcies are and were due to catastrophic medical bills or similar unforeseeable disasters, not to irresponsibility.)

There’s a difference between predatory lending and fraud. As I said before, a lot of lending practices are legal but wrong. It should be illegal for a lender to make a loan they know the debtor can’t pay back, and if they are found to have made such a loan they should be required to compensate the debtor to the tune of, say, three times the original or current value (whichever is greater) of the collateral. That would end predatory lending in a hurry.

It’s also common practice nowadays for all of a person’s creditors and insurers to jack up their rates after one late payment. If you’re living on the edge and paying, say, 15 percent on three credit cards, how does having all those rates raised to 25 percent make you more likely to pay your debts? It’s normal to charge a higher rate to begin with to a riskier pool of debtors, but to apply that reasoning to an individual makes no sense at all.

If you’re living on the edge and paying, say, 15 percent on three credit cards, how does having all those rates raised to 25 percent make you more likely to pay your debts?

It doesn’t, nor is it supposed to. Instead, it adjusts the credit companies’ return on its investment in you, on the not unreasonable grounds that the chance you’re going to rabbit or bankrupt has just gone up.

Instead, it adjusts the credit companies’ return on its investment in you, on the not unreasonable grounds that the chance you’re going to rabbit or bankrupt has just gone up.

But, now that my interest rate has gone up 60 percent (which seems wildly disproportionate to the increased chance that I’ll default, but set that aside), the chance that I’ll be able to pay what I owe has gone down, even more if multiple creditors and/or insurers do it simultaneously. If the creditors want me to pay what I owe (or what I would have owed), jacking up my rates seems counterproductive.

The second part (where the company making a loan that doesn’t get paid off) is highly unlikely to happen since they are able to make money on all the people who ARE paying and are paying insanely high rates, etc.

Hm. Good point. Perhaps I did go a bit far. OTOH, don’t go too far on “all the people who are paying insanely high rates”, either. What fraction of mortgagees took out a sub-prime mortgage and are paying “insanely high” interest rates? It’s true that the makers won’t go bankrupt, but whoever is holding the loan at this point will take losses where they had budgeted for profits. Do that enough and you will go bankrupt, or at least lose your investors.

Not to mention that in the case of a secured loan (such as a mortgage) the creditor ends up with the collateral and can resell it and incur little if any loss,

Don’t be so sure. In the current market in the Chicago area, anyway, there’s lots of homes that are either just even with the market or even upside down, where the home is worth less than the loan balance. Home prices have slid, new construction is down. And then there’s the expenses that the loan company incurs in taking possession, cleaning the place up and repairing any damages, etc., and then selling the house. Loan companies don’t want to get into the real estate business; it limits their losses but is not a profitable business for them.

The bottom line is that the kinds of governmental intervention that I favor here would be to prosecute fraud where it has occurred and provide regulation where needed. If a company qualified someone for a loan by misstating their income or ignoring adverse information, then it seems to me they’ve committed fraud.

Don’t forget that most mortgage loans are not held by the company that wrote them for more than a year; after that, the maker generally sells the loan to another company. I don’t know if sub-prime loans are different, mind you. But if not, if the writer qualifies someone for a loan when they were not in fact qualified and then sells that loan they’ve committed fraud against both the mortgagee and the company they sell the loan to.

However, if the person was fairly qualified for a sub-prime loan and then fails to pay for whatever reason, that’s not a problem for the taxpayer, just as if someone is fairly qualified for any other kind of loan and then fails to pay it.

“Don’t forget that most mortgage loans are not held by the company that wrote them for more than a year; after that, the maker generally sells the loan to another company. ”

Ours was sold 3 times in the first year of our mortgage. It’s crazy. We didn’t have a sub prime loan, but we did do an 80/20 split ( which in hindsight was stupid and I’ll never do it again). And the rate on our 20% loan is embarassingly high. EMBARASSINGLY high, and the rate on the 80% loan isn’t fabulous either. At least I made them fixed rates (thank god for small amounts of common sense).

We’ve hit some rocky times and the mortgage has been late multiple times. But, it’s still getting paid – trust me, the loan company is making PLENTY of money off of us. (So much so that it makes me angry), but in all honesty, ours is not a case of predatory lending – we had different information about annual salaries, etc at the time we bought and one month later my husband was laid off with no notice. But I digress.

I will agree with the poster who said that home ownership is not always in the best interest of poor people or working poor or even lower middle class folks. Part of the reason our situation has been so prolonged is because we are stuck in our house. We couldn’t resell it so soon after buying it and make back enough to pay real estate fees and the bank loan (especially since we had no money down, so there’s literally no equity in the house at all). In additon, we have been unable to do basic upkeep and repairs that are necessary. Thank goodness nothing disasterous has happened (knock on wood), but I’m sure our neighbors hate us – last year we had a tornado (which is crazy since this is the NE) and some large branches broke off the tree and fell into the yard. Thankfully, it didn’t damage anything, but the huge branches and brush are still sitting in our yard because we can’t afford to have it chopped up and disposed of properly… If anything, we are LESS invested in our neighborhood and city because we are fighting so hard to keep our heads above water I don’t have the time or resources for anything else. I have wished many times in the last 2 years that we were renting and could be in a cheaper place or at least FIND a cheaper alternative, as it is, my housing payment is fixed and fixed at as much as 50% of the monthly income at one point.

On the other hand, since we have certain things going for us, whiteness, education, etc, we have the potential to scrape out of this mess, but it’s gonna take a lot longer than it did to get into it. Although in hindsight, some of what we are dealing with is our own damn fault (we had no where near enough savings or cushion as an emergency fund and thus should have waited before jumping in to home ownership), some of it has just been unfortunate circumstances that are compounding over time.

I guess my point is that while it’s true that the individual buyers have to take some responsibility for their mistakes, there are some systematic problems that contribute to making those mistakes worse than they might otherwise be. It’s not always so simple of “personal responsibility.” I don’t have any solutions except to offer caution to anyone I see starting to follow in our footsteps!

Doesn’t this further undermine the argument that the initial lender will eventually go bankrupt from making bad loans, at least within a time frame that would limit the potential economic damage? Isn’t it also true that the secondary lender will likely sell the loan in turn? Can’t this process be repeated numerous times before the crunch comes? In the meanwhile, what’s to stop the initial lender from closing shop and starting up business under new articles of incorporation? How many homeowners in foreclosure are likely to pursue civil or criminal action rather than seeking relief through bankruptcy? How realistic is it to assume that every lender in the chain of reselling would be ignorant of the nature of such loans? How likely is it that any corporate entity other than the initial lender would be called to account?

The idea that somewhere, sometime down the road , someone might be held accountable isn’t much of a deterrent in such a setup.

The abstract theory of the self regulating market is wonderful, so long as you don’t take too close a look at reality.

Doesn’t this further undermine the argument that the initial lender will eventually go bankrupt from making bad loans, at least within a time frame that would limit the potential economic damage? Isn’t it also true that the secondary lender will likely sell the loan in turn? Can’t this process be repeated numerous times before the crunch comes?

The value of a bond is determined by the discounted value of it’s future payments. That discount rate is based on the risk associated with the loan. It includes not just the present value of the future payments but also the risk associated with inflation and default. The risk of default depends on both the liquidity of the borrower and the future value of the collateral. So in a falling housing market with rising foreclosures the value of the loan is going to decrease and the company that’s holding it now will have to sell it for less than they paid. In other words, they’ll loose money.

Sub-Prime loans were made more possible by the housing bubble. Since the future value of the collateral was expected to rise the discount rate was assumed to fall and the loan became more valuable. Sine this isn’t true anymore there aren’t as many places willing to buy the loans and the companies that originated them don’t have the capital they need to keep making loans. So they go out of business, or at least leave the Sub-Prime segment of the market.

The person you want to ‘hold accountable’ is the loan originator, not the company that lent the money. Loans are products like anything else. As someone pointed out up-thread Sub-Prime loans have done some positive things. It’s the salesman that mis-represented the terms and risks of the loan. This assumes that the lending institution wasn’t involved in trying to defraud the borrower. If they were, they’re also liable.

Kate:

How high?

Lu:

Creditors don’t make loans they know the debtor can’t pay back. That would be stupid. They make risky loans which the debtor might not be able to pay back. So how sure should they have to be, and how would you determine when they weren’t sure enough? Doesn’t this create incentives for people to try to get loans they can’t pay off, or, having been issued a risky loan, get themselves into situations where they can’t pay it back?

Why are you treating the debtors as innocent victims, anyway? If it should be illegal to issue risky loans, why shouldn’t it be illegal to take them out?

The message I’m getting from the comments here is that the poor are just too stupid to be trusted with significant amounts of credit. If that’s what you really believe, fine. But how many of you would be slamming banks for denying the poor access to credit if they actually stopped engaging in “predatory lending?”

This argument presumes that the practice of reselling loans as described is the product of a declining market as opposed to being a pre-existing pattern of business. Is that your contention?

You now appear to be arguing that the pattern of reselling was a product of the boom rather than the bust. In which case your previous explanation loses its credibility. Further, if the origin of the loan lies in boomtimes and the boom produced the cycle of reselling, then the likelyhood is that the majority of bad loans are no longer held by the originating lender. That such lenders will change business practice in light of the bust does nothing to deter them in future and it certainly doesn’t insure that they will go out of business, since they have already taken the greater part of their profits.

If the loan originator acted as an agent of the lending institution there is the question of negligence as well as active participation. The question of negligence pervades the entire chain of reselling. If you sell a substandard or injurious product, you cannot escape culpability by citing the fact that someone else sold it to you first. You must demonstrate that you satisfied the requirements of due diligence. Otherwise you are liable through negligence.

Only stupid if the creditor has no means of realizing a profit short term by offloading the liability onto someone else.

Only stupid if the creditor has no means of realizing a profit short term by offloading the liability onto someone else.

Few financial institutions are in business for the short term. Yeah, you can turn around your portfolio of crappy loans…once. The next cycle, who’s going to buy from you? The other players in the loan buying market (unlike the poor folks that predatory lenders target) have access to good information – like, the performance of the loans they bought from you last year. If the performance is lower than what the estimates of same predicted…you don’t have a customer any more.

Go to the next buyer? Sure…but eventually people start to wonder why you never get any repeat customers for your loan sales, and you’re out of luck.

I don’t doubt that there are a fair number of predatory lenders out there, but it really isn’t possible for a company to stay afloat making bad loans unless a government, or some other discretionless agent that can’t engage in commonsense declining to trade, is involved.

W.B. Reeves

That is not my contention. There can be many reasons to sell a loan. The value of a loan is give by present value of the future payments. This present value is determined by a discount rate that incorporates all risk associated with the loan. The current value off a loan can go up or down depending on interest rates, the value of the collateral, and the risk of default. Basically, they’re just another investment. Banks will buy or sell them for a variety of reasons. Well mostly just to make a profit. But the specific strategies can be complicated.

It’s debatable who’s doing the selling and who’s doing the buying in the home mortgage market. In practice the home owner feels like the buyer but that’s psychological. I’m offering you 500$/mo for 30 years in exchange for $85,000 today. Does it matter if I rewrite the sentence as You’re offering me $85,000 today in exchange for 360 monthly payments of 500$? I suppose if you call me you’re selling, but if I call you I’m selling. If you put an add in the paper does that make you the seller? What if I call every lender I can find? In principle a home mortgage and a corporate bond are the same thing. Does that mean that GE isn’t selling bond anymore?

I think both parties have an obligation to honestly represent all relevant information. If the loan originator obscures the fact that payments might change, or how this would be governed I think they’re guilty of fraud. If they create a loan they expect not to be paid back in anticipation of colleting fees and penalties (e.g. check cashing) I think they’re engaging in predatory lending.

True. But in that case you’d have to show both that the loan originator was a cooked and that the bank was negligent.

True, but there’s nothing wrong with the loan itself, the structure of the loan is fine it’s the way it was created that was the problem.

Say you sell me a sup-prime loan in Atlanta. (Let’s assume that you did so to collect origination fees. Let’s assume that you intentional obscured the terms of the loan from me. And that you strongly suspected that I would default. Let’s also assume that you leave a paper trail so there’s no doubt as to what you did. The bank you work for (Bank 0) takes that loan and 1000 others of similar risk and sells them to Bank A. (lets assume Bank A buys them and 9000 more because Bank A expect that housing prices will appreciate and thus the loans will become more valuable). Interest rates go up. Bank A decides it can get a better rate of return on it’s 8.6million dollars in the stock market and sells the loans to Pension Fund B. (Let’s assume that Pension Fund B expects interest rates are too low due to all the recent stock buying. So they want to get something that will go up in value quickly as bond prices rise.) Mutual Fund C comes along and offers to buy the loans from Pension Fund B at a slight premium. (Mutual Fund C is a publicly traded fund that specializes in the housing market, but they’ve accidentally concentrated too many loans in California and want to hedge against regional variation.

Now I find out that the loan you wrote has an interest rate that goes up every year. I know I asked you about that. I have notes of what you said. My lawyer finds your paper trail. But like many con artists you’ve left town and I can’t get any money from you.

Do you really think I have a claim of negligence against Bank C? If you do, and if you the courts agree with you I predict one of three things. Lawyers will find a way out of it, there will be less capital available to poor (risky) people, the interest rates for risky borrowers will go up to reflect the new risk. Most likely some of all three.

Creditors don’t make loans they know the debtor can’t pay back. That would be stupid. They make risky loans which the debtor might not be able to pay back.

If the loan is unsecured, yes, it would be stupid. If the loan is secured by collateral that’s appreciating, you get whatever payments you’re able to collect before the balloon payment comes due, plus you get to resell the collateral and at least break even. If you can pass the collateral (house) off to the real-estate arm of your company, a sweet deal indeed.

If OTOH you raise the interest rate on a credit card by 50 percent or more soon as a debtor misses one payment, you are indeed very likely making an unsecured loan that the debtor can’t pay.

And, yes, if a lender who failed in due diligence were required to compensate the debtor more than the value of the loan, some people would try to get such loans — which would put more of the burden back on lenders to minimize risk. I agree that a lot of people wouldn’t be in over their heads if they’d read the fine print, and that they should read the fine print, but why should ALL of the responsibility be on the debtor to avoid being screwed, and not on the lender not to screw people?

I also agree that if lenders made fewer risky loans, more people would be unable to get credit, but I think that would be as it should be.

It rarely works this way for houses. The foreclosure process is both long and public. It’s very hard to ‘surprise’ someone with the sale of their house. In a normal scenario there’s no equity left in the house. The owner has borrowed as much as they can get. Think about it, if you owed 10K on a 80K house and couldn’t make the payments you’d sell or refinance.

Most banks would rather sell short, (sell the house for less then the debt and either write of the loss or take a promissory note) than take ownership of the house. They have transaction costs associated with the sale just like we do. Most houses that go into foreclosure aren’t in great shape and often have tax bills that have to be paid off. Not slamming people that have lost their homes, but if you were struggling to make the house payment how much time and money would you put in curb appeal? If you knew you were being thrown out, what condition would you leave the property in? This makes it very hard for the bank to make back what was owed on the house

OK, so maybe it’s not that easy, and maybe I get a bit carried away with the evil-robber-baron thing. It’s very hard for me to understand 1) why anyone would take out a loan they couldn’t afford 2) why any financial institution would make such a loan. I hear these lurid tales of people who gross $5000 a month taking out loans with payments of $2000 a month increasing to $6000 a month after two years — those numbers are exaggerated, of course, but you get the idea. I can explain 1) as a combination of financial naivete and wishful thinking, but when I get to 2)… as I said before, these people crunch numbers for a living, so the only explanation I can think of is that they’ve figured out how to do OK even if the debtor goes bust. Or maybe, as Ron said, they think the taxpayers will bail them out.

Assuming that there’s no misrepresentation involved the obvious answer is that something changed. Maybe the borrower lost their job, had a child, had a lot of home repairs to make or lived beyond their means and got into credit card debt.

well, three years ago I bought a house on a 3 year ARM, with 10% of the down payment on a 15 year interest only loan. I’d been planning to move in three years so at the time it made sense. But if things hadn’t worked out the way I was planning I’d have been in a difficult situation. I basically had to move when I did no matter what, or watch my mortgage payment balloon. I wasn’t exactly walking on the edge, but I could have bought more house. Lenders are willing to assume the buyer will be house poor to a shocking extent.

well, there’s money to be made in lending money and a lot of people want a piece of it. So we get lot’s of lenders and lots of competition. People take more and more chances and eventually a company or two goes too far and goes out of business. Believe me, they screw up just like everyone else. You’ll see a lot of them go out of business or be bought out soon enough.

It’s very hard for me to understand 1) why anyone would take out a loan they couldn’t afford 2) why any financial institution would make such a loan.

Lenders figure that a house’s value will either stay the same or increase. Borrowers figure that their income is going to go up in time. Usually, they’re both right. But not always, and a downturn in the economy can create a lot of problems.

There have been a lot of new houses built in my area in the last decade. They’ve been getting bigger and more elaborate as the years go on. My son sold pancake breakfast tickets and Christmas wreaths every year for his Boy Scout Troop, and things being the way they are these days I didn’t just kick him out the door with a fistful of tickets or an order book like my parents did, I walked around with him.

It was very instructive. We would walk up to the front door of this 2500+ square foot home made of brick with nice landscaping, fancy masonry, etc. I’d look in the windows (from an appropriate distance, mind you) and see … nothing. No curtains, no rugs, no furniture. House after house people were putting all their money into the house itself. There’d be some toys around and about, but that was it. Oh, and the $30,000+ cars. The idea is that “Oh, we’re young, our salaries will go up and we can afford to buy furniture then.” Then they get laid off, or raises are down or flat (hell, one year I had to take a CUT). If one of them loses their job, they’re in deep doo-doo.

Me, I paid $90,000 for my 1700 sq. ft. house on 3/4 of an acre (for you metric folks, my house is on a lot 39 m x 85 m) twenty years ago, and it’s covered with aluminum siding, not brick (siding is considered much less desirable in the Chicago area). My lot is at least 3x the size that these larger houses are on, and unlike them is covered with trees and plants. If I sold tomorrow I’d get about $350,000 for the house, and the new owner would knock it and most of the trees down the next day and either build a much larger house on it or try to figure out how to split it up into 3 lots and build a house on each. I’d never sell, because I’d never be able to get equivalent housing for $350,000 anywhere nearby. I’ll only sell when I’m too damn old and feeble to take care of myself and the house anymore.

But the point is that I’m not house poor; even when I bought it I paid a much smaller multiple of my then annual income than these folks have, because I was afraid to commit more money than that. I also got a deal because the owner, whom my wife was distantly related to, gave us a $20,000 break on the price. We were renting a house in the neighborhood when she called us up one day; her husband (70+ years old) was in great pain and she wanted to take him to the hospital. Her son couldn’t be bothered, so we took him. He thought he was dying, but it turned out to be a kidney stone. This was remembered in our favor 5 years later when we looked to buy her home (which was not at all something we had anticipated at the time). But without that break we’d have bought another property in our price range. I’m also fortunate that over the 20 years after that I have gotten a reasonable raise almost every year.

Lenders figure that a house’s value will either stay the same or increase. Borrowers figure that their income is going to go up in time.

Yes, but (even though, as you point out, both are often true) I would be extremely leery of basing my own financial health for the next n years on these assumptions. It’s also important to note that (as you also point out) while they’re almost always true in the long term, in the short term things can get much dicier, and the fact that I’ll get another job or my house’s value will appreciate in six months doesn’t help a whole lot if the sheriff is at the door this minute.

When you talk about personal fiscal responsibility, not overextending yourself and not buying fancy stuff you don’t need, you are actually singing out of my hymnal (as it were). I do think the responsibility should be a two-way street between lenders and borrowers. The irony is that I clearly recall that when we bought our second house the mortgage banker we worked with made sure that we could do the down payment with a pretty comfy cushion, which I think we needed to qualify for the type of mortgage we were getting.

People who have the cushion and can do a traditional 20-percent-down mortgage get offered the best rates; the people who are living closest to the edge are the ones who can only get riskier loans at higher rates. Now, I do understand why this is, that the higher the number of people in a given pool who statistically will default, the higher the interest rate on loans to that pool needs to be in order to make a profit on that group of loans as a whole. But it does seem like a self-fulfilling prophecy: if you’re one or two paychecks from insolvency to start with, and you have to pay higher rates, and your interest rates on your credit cards suddenly double because you miss one payment, of course you’re more likely to default. And after a certain point I have trouble with the ethics of it. Not everyone is pathologically risk-averse (I’m not labeling anyone else that, just myself), and I don’t think lenders should encourage people to bet the farm.

Oh, and the folks who go into ear-deep hock to buy the mcmansion and the beemer when they should bloody well know better, I don’t cry over. (Although I still don’t think lenders should abet them in their idiocy.) I do feel bad for people who are just starting out and bite off just a little too much.