Summary: There is a lot of racism in the history of the US minimum wage – but the most important way that racism has been expressed is through exemptions to the minimum wage law which have kept workers of color from being protected as well as white workers. And evidence suggests that the minimum wage law does not increase unemployment amongst black workers.

On another thread, Jut wrote:

And, let’s face it: minimum wage laws were designed to price black people out of the labor market; why should we be surprised that they accomplished that goal?

It’s true that the history of the minimum wage is shot through with racism, including occasional examples of racists wanting a universal minimum wage in order to price non-whites out of the labor market. But the main way racists in the US have effected minimum wage law is by making exemptions for jobs that are primarily held by workers of color.

The first federal minimum wage law in the US was the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. But racist Southern Democrats lobbied heavily to exclude some classes of workers, especially agricultural workers, from the FLSA. For example, Florida Representative J. Mark Wilcox, debating the FLSA in 1937, said:

Then there is another matter of great importance in the South, and that is the problem of our Negro labor. There has always been a difference in the wage scale of white and colored labor. So long as Florida people are permitted to handle the matter, this delicate and perplexing problem can be adjusted; But the Federal Government knows no color line and of necessity it cannot make any distinction between the races. We may rest assured, therefore, that … it will prescribe the same wage for the Negro that it prescribes for the white man. … [T]hose of us who know the true situation know that it just will not work in the South. You cannot put the Negro and the white man on the same basis and get away with it. Not only would such a situation result in grave social and racial conflicts but it would also result in throwing the Negro out of employment and in making him a public charge.

As historian Juan Perria wrote (pdf link, long but excellent):

Specifically, southern congressmen wanted to exclude black employees from the New Deal to preserve the quasi-plantation style of agriculture that pervaded the still-segregated Jim Crow South. While they supported reforms that would bring more prosperity to their relatively poor region, they rejected those that might upset the existing system of racial segregation and exploitation of blacks.

President Roosevelt and his legislative allies recognized that in order to pass any New Deal legislation at all, it was necessary to compromise with Southern Democrats intent on preserving white supremacy. The compromise position was race-neutral language that both accommodated the southern desire to exclude blacks but did not alienate northern liberals nor blacks in the way that an explicit racial exclusion would. An occupational classification like agricultural and domestic employees, excluding most blacks without saying so, was just such race-neutral language.

In the decades since, anti-racist activists in the US have fought long and hard to reduce and eliminate those occupational classifications, with some success.

But what about Jut’s second claim – “why should we be surprised that they accomplished that goal?” Have minimum wage laws actually priced Black workers in particular out of the labor market?

Good empirical studies haven’t supported Jut’s assertion. From John Schmitt’s overview of the research (pdf link):

As Allegretto, Dube, and Reich note, however, a theoretical case can be made that minimum wages might instead improve the relative employment prospects of disadvantaged workers: “An alternative view suggests that barriers to mobility are greater among minorities than among teens as a whole. Higher pay then increases the returns to worker search and overcomes existing barriers to employment that are not based on skill and experience differentials.”62 A higher minimum wage could help disadvantaged workers to cover the costs of finding and keeping a job, including, for example, transportation, child-care, and uniforms.

Allegretto, Dube, and Reich’s (2011) own research on the employment effect of the minimum wage on teens looks separately at the effects on white, black, and Hispanic teens. For the period 1990 through 2009, which includes three recessions and three rounds of increases in the federal minimum wage, they find no statistically significant effect of the minimum wage on teens as a whole, or on any of the three racial and ethnic groups, separately, after they control for region of the country. Using a similar methodology, Dube, Lester, and Reich (2012) detect no evidence that employers changed the age or gender composition in the restaurant sector in response to the minimum wage. In a study of detailed payroll records for a large retail firm with more than 700 stores, Laura Giuliano (2012) found that teens from more affluent areas increased their labor supply (and employment) after the 1996-1997 increases in the minimum wage, while employment of teens in less affluent areas experienced no statistically significant change in employment.

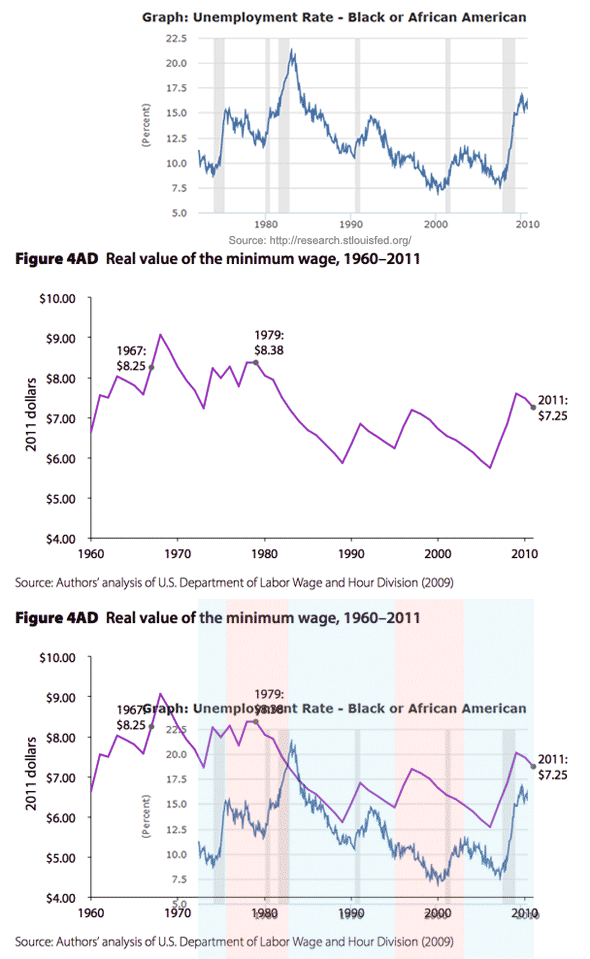

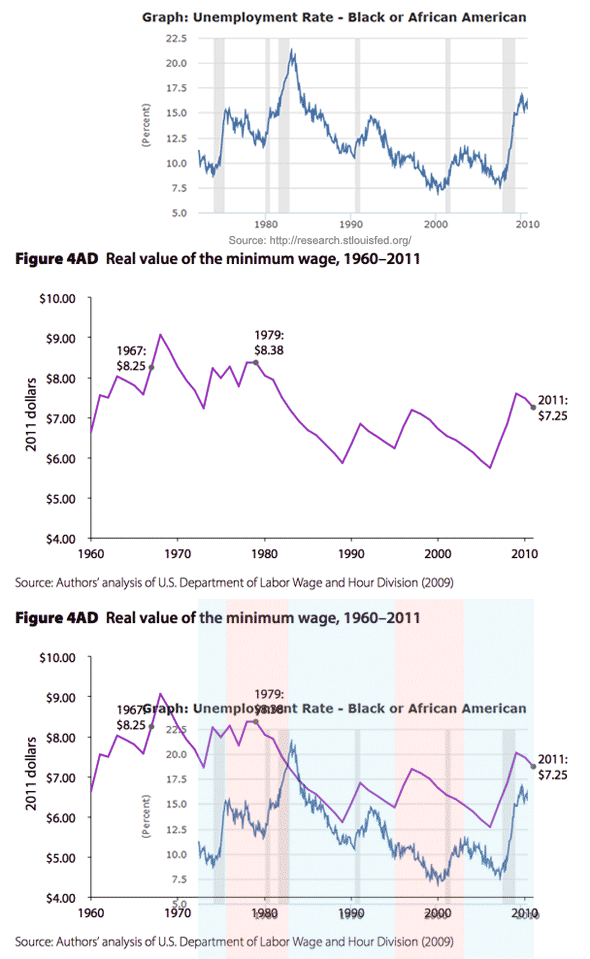

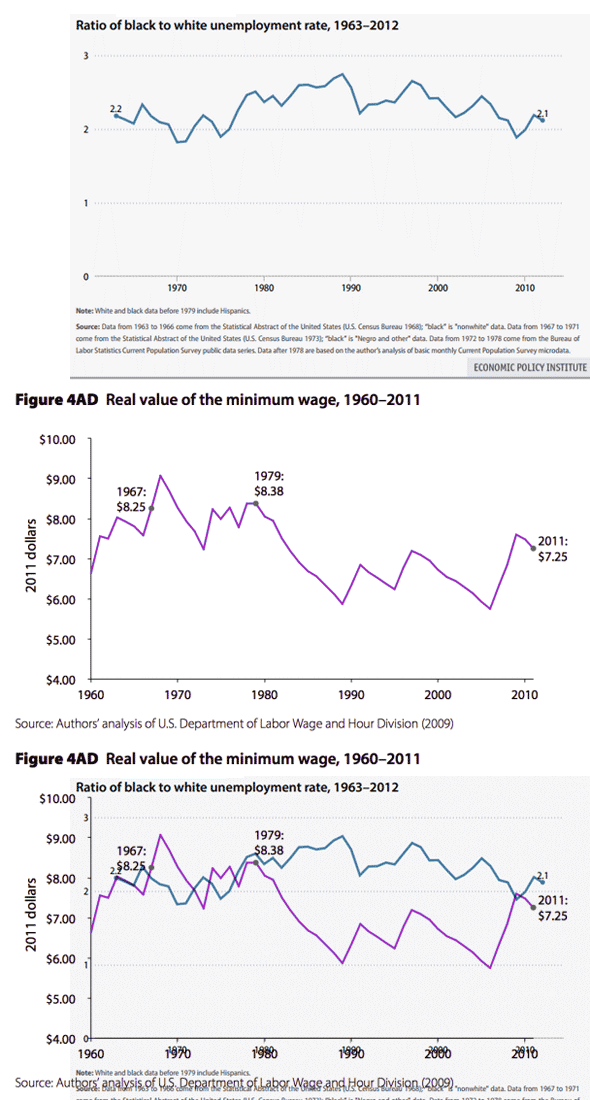

We can also look at this in a cruder way: Does Black unemployment actually move up and down with the value of the minimum wage? Here are three graphs: A graph of Black unemployment, a graph of the minimum wage, and then an overlay showing the two graphs together.

There are major periods (marked in blue in the overlay) in which black unemployment and the value of the minimum wage seem to be moving together. But there are also major periods (marked in pink) in which they seem to actually be opposites. Overall, it’s hard to argue, looking at this, that the correspondence is anything more than chance.

Furthermore, there are two big problems with arguing that the areas of correspondence shows that black unemployment is being drive by the minimum wage. First of all, Black and white unemployment rates virtually always move up and down together (although the Black unemployment rate is always higher). So it’s hard to argue that the minimum wage is causing unemployment amongst Black but not white workers.

Secondly, and more importantly, look at those gray bars in the chart of Black unemployment over time. Those mark recessions. And when you look at that, it becomes obvious that changes in unemployment rates are overwhelmingly driven by recessions. During recessions (including the time before and after the recession), and at no other time, unemployment rises steeply. After recessions, and at no other time, unemployment drops. The longer the time between recessions, the longer the drop.

Once you notice the link to recessions, it’s hard to see how the minimum wage can be the driving force behind black unemployment.

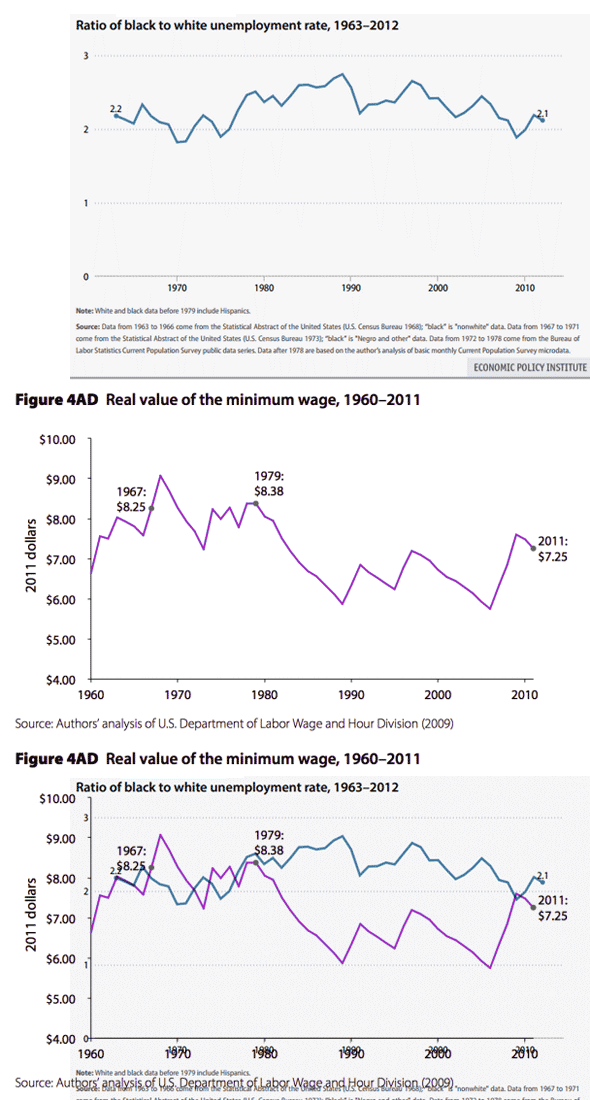

But maybe looking at Black unemployment is my mistake. If the idea is that higher minimum wages cause employers to favor white employees more, wouldn’t it make more sense to look instead at how the minimum wage corresponds with the ratio of Black to white unemployment? Yes, it would. But:

Again, no support for Jut’s theory there.

P.S. I just added a minimum wage category to “Alas,” for those who are interested.

Am I the only one who read "Beware the narcoterrorists" and thought "beware the jabberwock"?