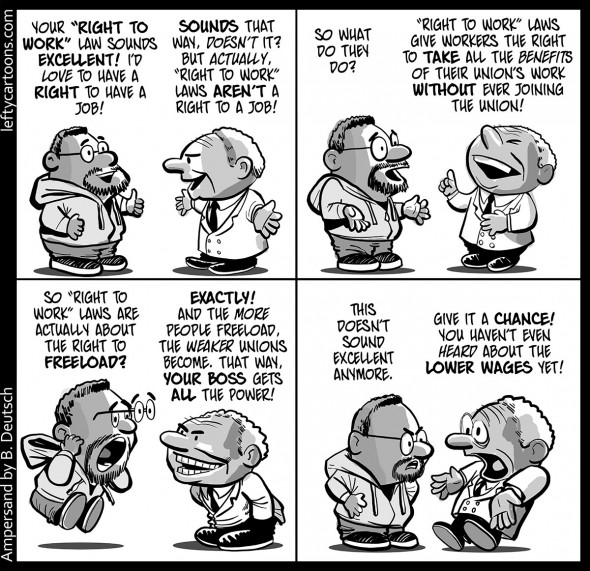

Transcript of cartoon.

Panel 1: A Young Guy in a sweatshirt is talking to a well-off looking older man, who is wearing a double-breasted jacket and a tie.

SWEATS: Your “right to work” law sounds excellent! I’d love to have a right to have a job!

TIE: Sounds that way, doesn’t it? But actually, “right to work” laws aren’t a right to a job!

Panel 2

SWEATS: So what do they do?

TIE: “Right to work” laws give workers the right to take all the benefits of their union’s work without ever joining the union!

Panel 3

SWEATS: So “right to work” laws are actually about the right to freeload?

TIE: Exactly! And the more people freeload, the weaker unions become. That way, your boss gets all the power!

Panel 4

SWEATS: This doesn’t sound so excellent anymore.

TIE: Give it a chance! You haven’t even heard about the lower wages yet!

Is that Calvin all grown up? (Especially panels 1 & 4)

I don’t remember seeing another character of yours that reminded me of him the way those two panels do.

I hadn’t INTENDED that, but now that you point it out…!

I agree with Jake. I wish there had been a follow-up showing Calvin as a college student, and then an adult.

RTW laws have a lot of effects. The most basic three results are:

1) preventing “union shops” where you literally cannot get a job without being a union member and thereby subjecting yourself to union rules.

2) allowing nonmembers to be covered by* union negotiations without paying for it. IOW, a union may negotiate general conditions for workers; and a company may implement those conditions generally; without regard for whether the workers are union or not. In many cases this is because they don’t want to have two different sets of worker rules, pay scales, etc.

With respect to #2, it’s worth noting that in most situations where the union would be doing this anyway, the marginal cost to the union is basically zero (the reps are there; the reps are negotiating; the reps don’t cost more if they do so for 10,001 or 10,000 employees.)

Also with respect to #2, it’s worth remembering that negotiations generally involve tradeoffs. Maybe you trade higher pay for lower pensions, or the reverse; maybe you trade job security for opportunity for quick advancement; and so on. The fact that Sally Superior can’t get a job of choice, while Emmett Experienced is at no risk of being replaced by Sally (who would be a better employee) unless Emmett does something seriously wrong…. well, that system may not actually be in Sally’s best interests. Those are matters of considerable dispute. Although the union is negotiating “for the workers” that tends to be based on averages, and most people aren’t average. There is no guarantee that the union’s tradeoffs–which are determined by union management and/or membership–will suit the wishes of any particular non-members.

3) Allowing nonmembers to benefit from union work which does cost the union money. E.g., that the nonmember can use union grievance reps and procedures even if they’re nonunion. This, unlike negotiation, does have a cost.

#3 is a bit trickier in practice, of course, because the unions are well aware of this requirement at the time that their well-informed representatives do the negotiating in the first place. So the “unfairness” aspect is reduced somewhat but still exists.

As with all things, this is a tradeoff. For me, I would be perfectly satisfied if RTW laws were limited to #1-2. And I’m not even sure how I feel about #1, to be honest. While I generally think that high entry costs are a bad thing, I don’t know if it makes sense to totally forbid folks from contracting to use them.

Which of those would you consider to be a viable tradeoff? Would you drop your objections if #3 were gone? Do you think that any of the RTW arguments have traction?

* The anti-RTW folks always refer to this as “benefiting” from negotiations, but not all outcomes of union negotiations will benefit all employees. To use a simple example: Say (a) you were the World’s Best 5th Grade Teacher and you wanted to work in your local 5th grade; (b) the existing teacher is “above bad, but not outstanding” and certainly not as good as you; and (c) the students and school would benefit if you worked there. You can’t get his job, though, because he can’t be replaced by you as per contract. Now, you can make an argument that on average the union arrangement will lead to better outcomes long term, but that doesn’t change the fact that for you it will not lead to your getting the job you want.

Susan:

Well, then! You ought to read these strips by Dan & Tom Heyerman & Hazel Mae Donovan. They’re called “Hobbes & Bacon.”

1

2

3

4

—Myca

Those are awesome–thanks, Myca!

http://m.tickld.com/x/this-guy-just-changed-the-way-we-seecalvin-and-hobbes

I got a kick out of this Calvin and hobbes fan fiction myself, pretty sentimental, but nothing wrong with that.

Also, it can be different between public employee unions and private-sector unions. Sometimes one type of union is allowed to charge non-member employees a “fair share” fee, which is supposed to be the cost of bargaining and contract administration but not include the cost of any other union activities normally funded through dues (such as political activity).

In my experience, no matter how superior Sally Superior is, without the benefit of collective bargaining, she’s not going to get optimal raises and benefits. Only very well connected, highly placed individuals (think CEO’s, hedge fund managers – jobs which are never unionized anyway) have the power to individually negotiate higher wages and better benefits with the major corporations which employ the majority of people. People integral to the running of a small business like yours might have such power as well. But, again, they don’t tend to be unionized either.

If Sally Superior feels the same way, she will join the union. Problem solved.

But the question is what happens when Sally does not agree with you. Perhaps she thinks that she is a better judge of her future than you, me, or anyone else.

Sally Superior might not be eligible to join a union-she might have enough supervisory responsibility to exclude her from the bargaining unit, or be a confidential employee.

Not if she can freeload and get the benefits without paying the fees.

OK. So Sally is now

1) smart enough to get a job;

2) not smart enough (or a good enough negotiator, or powerful enough) to get the conditions she wants without a union;

3) not able to see that those union benefits are worth joining, i.e. not smart enough to have any long view; and

4) morally interested in freeloading.

I don’t see a lot of respect for Sally’s autonomy in there.

For example: Here’s an interesting post from a conservative teacher. He attaches a letter from the union arbiter, relating to his fair share fees. (Before you read it: What percentage of the NEA fees do you think go towards benefiting that teacher?)

Like that poster, Sally can reasonably conclude that even her fair share fees are going to an organization which has goals, methods, and political causes that she opposes.

Where are all the free choice folks on Sally’s side, here?

gin-and-whisky: If the teacher in question were male, maybe he could have negotiated for a better package, but women receive lower offers and are perceived as worse people when they ask for more in the same ways that men do and are rewarded for.

As for fair share-that letter is from the union, not the arbitrator, and it encloses a rebate of the portion of his union dues that the arbitrator decided was not related to bargaining and contract administration. Just like they’re supposed to do. So while the money (like taxes) is going to an organization (like, say, the government) which has goals and spends the money in ways she opposes (like, say, building a bridge to nowhere), she at least only pays the portion going to the things she directly benefits from (like, say, roads; only in this case it’s bargaining for higher wages and better benefits, or maybe a class size limitation).

Part of the NEA dues go for legal insurance-they cover your civil (not criminal) attorney fees if you are accused of wrongdoing, or threatened with withdrawal of your teaching license for something that isn’t justified; the dues also cover attorney fees if you’re wrongly laid off or if your pension isn’t properly credited for work you’ve done and contributions you’ve made. Although those things are only covered for actual members, which explains why so much of the NEA portion is refunded — 66% is refunded.

As for her autonomy-surely she wouldn’t want to work for the government, then. There’s very little autonomy in most government jobs, especially teachers. She might choose to teach at a private school or a charter where there is no union. She’s not restricted to teaching at a public school.

OK, so now she’s smart enough to deserve a good job, but not smart enough to agree with you (assuming she should) that that she can’t get it absent union help?

Or perhaps she’s smart enough to agree with you (assuming she should), but she is making the “wrong” choice to go for it on her own anyway instead of the Kai-approved “right” choice to unionize?

Or perhaps she is smart enough to agree with you (assuming she should) about her chances, and to agree with you (assuming she should) about the benefits of unionization… but has her own reasons for making the tradeoff, which you don’t know?

Only somewhat snarkily, would you like a remote control over all of Sally’s life, or just the part of her life that controls her working pay and conditions?

It is really surprising to me, Kai, the degree to which you’re willing to assume pretty much everything possible about Sally, other than the fact that she simply doesn’t feel the way you do. I don’t understand what is so hard about that. Your position is fine but it sure as heck isn’t so strong as to have a challenge be ridiculous.

I mean, if you were saying “screw Sally’s choices or desires. She needs to suck it up and be unhappy for the greater good” that would at least make sense, and we could argue about that. If you were saying “I know what Sally wants/needs better than Sally does” that would at least make sense, and we could argue about that.

But you seem determined to basically claim that Sally doesn’t exist, or that everything about her choices can be explained by some factor other than autonomy. Hell, I linked to someone like Sally: a die hard republican who basically hates everything the unions stand for and wants to be disassociated with them entirely, but is forced to work with them because of state law. And your response is, basically, “well, he’s not female.” This is not serious argument.

Well, no. Not at all.

Unions are nongovernmental bodies, without the same levels of protections and oversight; they are not at all like taxation. Also, they’re not part of the social contract in the same way. The analogy focuses only on things like “dues” and “work,” and thereby glosses over the crucial distinction between them.

I hesitate to suggest that you’re not able to really think about the other side–it’s a bit ad hom, and I regret it–but I am having a hard time understanding what else could be going on here. Because while there are a lot of arguments in favor of unions (which I am happy to acknowledge) and while there are a lot of arguments that unions are beneficial overall (I acknowledge these as well) you seem unwilling to seriously acknowledge any of the cons, or any of the arguments against unions. This makes discussion with you difficult to say the least. I don’t see you as a viable discussion partner at this point.

Eh, strawman. First, I’m not actually in favor of public employee unions-I think they’re unethical, a conflict of interest between taxpayers-as-employers and taxpayers-as-employees. I just know a lot about them because of my job as a legal secretary at a firm that represents a lot of public employee unions–and some private ones. You think people who present data that doesn’t support your side automatically disagree with you? That’s not efficient. Better to be able to counter the arguments.

Also, my assumptions aren’t about Sally so much as they are about society–it’s proven that women are perceived as less competent than men even when the same resume is submitted with only a name change, that women are given lower compensation offers than men, and that when women use the same techniques to ask for a compensation bump that men do, they are perceived as “greedy, demanding or just not very nice.” CNBC. None of that has anything to do with Sally. It’s cultural.

As for my analogy, you don’t have to like it and I freely admit it’s flawed: that’s true of most analogies, they don’t perfectly represent the situation but may provide useful similarity to aid analysis and understanding. Public employee union dues/fair share payments are very much like taxes; although you can’t get jail time for failing to pay your dues/fair share, you will lose your job. I’m angry about how the government uses some of the money I pay in taxes, but I don’t even get the fair share option.

Just a bit ad hom? You seem to be making a lot of inaccurate assumptions about me without knowing me; by contrast I am responding to the arguments you’ve made using the imaginary scenario already under discussion, from a position of some daily knowledge about public and private unions.

All I’m arguing is that unions do what they are designed to do – get employees better wages and benefits than they could get on their own. Most people are not specialists in negotiating for wages and benefits, whereas large institutions (where most people in union jobs work) hire people specifically for that purpose with expertise in that area. They also have basic information, which employees generally don’t have, like what other employees make.

So, yes, I think anyone who is in the sort of job which is unionized, and objects to unions on the grounds that he or she could somehow get better wages and/or benefits if the union would just get out of the way is a fool on this particular topic.

Now, if people are against unions even though they know that they will almost certainly wind up with lower wages and benefits without them – maybe they’re pro-life and object to the support of pro-choice candidates – I support their right to only pay for services which apply to the job, like negotiating wages.

It’s my experience that people who refuse to acknowledge the other side’s salient points; or who won’t concede at least some weak points in their own; aren’t usually arguing honestly. You seem to be an exception, but that wasn’t clear to me until your most recent post.

Assuming for a moment that’s true, that isn’t necessarily something unions will address: if Sally is perceived as “bitchy” the union doesn’t care. W/r/t employment compensation, the question in the control of unions is more “if you control for all extraneous factors, is there a difference in the end salary?” and the more that studies actually control, the closer they get to an answer of “nope.”

[Shrug] You picked what is literally the oldest and most established and complex form of “mandatory group membership” and frankly the analogy is horrible. Because whether you are talking about violence, taxation, representation, or regulation, there’s “everything else” and there’s “the government,” and it’s a bizarre line to cross.

I have no interest in having a general discussion about the morality of taxes overall, or of side tracking into debates about government generally. There are a gazillion groups out there and only the government has special superpowers to do basically whatever the hell it wants based on whatever laws it passes. The government is substantially and materially different in so many ways that I can’t even understand why you’d choose that.

Want to talk about mandatory group membership to work in religious arenas? Functional discrimination against other choices? Use a real analogy.

Which is irrelevant. See above.

Honestly, I don’t actually think you’re “responding to the arguments you’ve made using the imaginary scenario already under discussion” as much as you are taking an intentionally-general hypothetical; finding specific counterexamples which don’t necessarily generalize; and making what seems like a very strange analogy.

Kai Jones:

The following reflects my views on public employee unions:

But the question is what happens when Sally does not agree with you. Perhaps she thinks that she is a better judge of her future than you, me, or anyone else.

OK. She can think whatever she wants.

But why should her fellow employees be constrained from striking the best deal that they can with their employer for Sally’s benefit? Why is this particular form of contractual arrangement, where employers agree to only employ union members, so incredibly destructive that they must be prohibited by law?

In any economic rule – including no rules at all – there are people who do worse under that rule than they would under another rule. There are people who might be better off without a minimum wage law; there are children whose lives might be improved if they could get legal employment; etc etc..

The mere fact that we can point out these cases is not enough to show that the rule is a bad idea.

In the case of “right to work,” as Pillsy rightly points out, what right to work advocates want is for the majority of workers and employers to be constrained by law from negotiating a deal they’d otherwise negotiate. (There’s no need to pass a law to prevent a minority of workers from striking such a deal, because you need a majority to form a union). But unless you think the majority of workers don’t know what’s good for them, I can’t see how that’s a good deal for workers.

Edited to add: Please strike the phrase “don’t know what’s good for them,” and replace it with “are less likely to be able to choose what’s best for themselves than the people who write right-to-work laws.”

Anyone know of a good resource along the lines of EUROPEAN TRADE UNIONS FOR DUMMIES? I’m curious how Germany or Finland do these things but I barely have time to study for my grad school classes as it is. I don’t want to have to hammer through Google translated web pages for a few weeks.

I don’t think that’s right.

What RTW advocates want can be summed up better like this:

You can negotiate a deal for YOU. Go nuts–I wouldn’t think of constraining you. You just can’t negotiate a deal for ME unless I ask. Neither can you prevent me from negotiating on my own, if I choose to do so.

And to the degree that you decide to negotiate on my behalf without my permission (or against my express wishes) you can’t then decide that I have to pay you for the unwanted negotiation.

If I’m a RTW advocate (especially of the libertarian bent) I frankly don’t care what deal you want to negotiate regarding your own work and pay. I just want you to leave me alone. So the concept that RTW is inherently about constraining YOU is almost exactly backwards. RTW is about preventing you from constraining ME.

I dunno, I consider union membership the same as any other sort of employment condition. Some places, you gotta wear a suit. Don’t like it, don’t work there.

—Myca

There is no such thing as a “libertarian” RTW advocate. By definition, RTW advocates are people who want the government to step in and use the force of law to prohibit workers and unions to freely negotiate certain kinds of agreements. That is the opposite of libertarianism.

Now, admittedly, many libertarians are “libertarian” in name only, and in practice they just favor trying to crush labor rights and favor employers in every way that is politically viable in the current climate. (Edited to add: I am not suggesting that G&W is such a person!) So in that sense, being RTW is being libertarian. But it’s certainly not libertarian in any principled way.

And maybe you don’t think gravity pulls down, but that’s not gonna make my shoes float up to the ceiling.

Right to work laws mean exactly what I just described. They mean that union security agreements are prohibited by law, even if workers and the employers want to negotiate such an agreement. They mean the government stepping in and outlawing a certain kind of agreement. There are minor variations from state to state, but as far as I know every single right-to-work law has this in common. If they didn’t, they’d be some other kind of law, not a right-to-work law.

Okay, I want to negotiate an agreement saying that I will only hire colorists who work for the colorists union (in exchange for access to those colorists, who I believe to be the most skilled and best-trained colorists). Can I negotiate that deal for ME, under the law you favor?

Amp:

Which kind of agreements?

Agreements that create closed “union shops” – basically forcing other workers to join the union, rather than negotiate their own deal.

Every major RTW victory – including the public-union cases – took the form of opening “union shops” to allow workers to opt out of the union.

Sounds like exactly the libertarian approach gin-and-whiskey was describing:

Technically, you’re wrong (more kinds of agreements are prohibited by RTW laws than just “union shops”). But broadly speaking, you’re right.

You’re wrong about workers being “forced,” however, especially from a libertarian perspective. Nothing about the existence of union shops prohibits workers from seeking jobs somewhere else. (Just as a workplace that requires office dress doesn’t prohibit workers who object to dress shoes from seeking a job somewhere else.)

So my question to you is, so what? You seem to think that if you play word games, that changed the fact that what you favor is having the government outlaw agreements that would otherwise occur if people could freely negotiate.

As I said to G&W, “I want to negotiate an agreement saying that I will only hire colorists who work for the colorists union (in exchange for access to those colorists, who I believe to be the most skilled and best-trained colorists).” RTW laws prohibit me from negotiating that agreement. You seem to be saying that I owe you a job under the conditions you demand, to the point that the deal I’d prefer to strike should be outlawed. How is that “libertarian”?

The business owner and (some) workers can come to an agreement and can carry out that agreement as long as both of them want to. The libertarian thing is that the government does not have to use force to *enforce* that agreement. That is a concept that has been put into practice: Some houses a century ago used to have clauses in the sale agreement that (1) the clause would be passed along to the next buyer and (2) the seller cannot sell to a black person.

Those agreements are still in effect (in a certain sense, I guess), but the government refuses to enforce them in its courts.

A second point is that you run into difficulty when agreements are formed that affect the rights of third parties. I can make an agreement with Joe that you have to pay me $100, but the government will not enforce that agreement. Barring someone from employment unless they pay you (the workers who extorted an agreement out of the business owner) a certain amount of money also doesn’t really sound like fair play.

And in many, many other areas, I don’t think I would hear the cavalier “just find a job somewhere else” from many on this board. Sexually harassed, find a job somewhere else. Owner won’t hire you because you’re black, find a job somewhere else.

You’ve conflated two things – “sounds like fair play” and “rights of third parties.” But even RTW advocates don’t claim that anyone has a “right” to unconditional employment at a particular firm. Therefore, there are no “rights of third parties” affected by union security agreements (which are what RTW laws outlaw).

I also like your use of the word “extorted.” So if a worker refuses to work unless the employer first negotiates and comes to an employment agreement, you consider that “extortion?”

You’re right, you wouldn’t hear me say it in those circumstances. (In fact, I didn’t say those precise words even here.) That’s because workers should have a right to have their job applications considered without regard to race [*], and to work without sexual harassment.

[* With a few obvious exceptions, such as actors auditioning for a non-raceblind part. Also, I’m not going into affirmative action here, but people can discuss it on the open thread if they want to.]

But there are zillions of other circumstances in which I would say “then you’ll need to find a job somewhere else.” If Sally says she won’t work at Lucy’s firm unless Lucy pays her in rainbow lollipops, Lucy is – and should be – free to say “sorry, I’m not going to employ you under the terms you demand. You’ll have to look elsewhere.” And if Schroeder says he won’t work for Linus unless Linus agrees to break the agreement Linus has already made with his other workers, Linus should be free to say “sorry, not interested, Schroeder.” But Linus doesn’t have that freedom in RTW states.

Is saying “they’ll need to seek a job elsewhere” cavalier? Maybe. But two points in my defense:

1) No market economy can function if employers are NEVER allowed to say “sorry, not hiring you – you’ll have to look elsewhere.” But the evidence shows that non-market economies suck for almost everyone, very much including ordinary workers. So accepting that it is necessary, in a market economy, for workers to sometimes look for jobs elsewhere, is pragmatically kinder than forcing firms to unconditionally hire all comers.

2) I favor very generous subsidies for unemployed people.

OK, seriously?

The government is already using the force of law to support all sorts of agreements. Unions don’t exist in a vacuum; they exist in a legal climate which gives them enormous advantages over their “natural state.”

RTW advocates are trying to limit those advantages. If you wanted to get rid of all laws which were aimed at unions–including laws which grant unions special protections, etc.–then libertarians would be fine, and these changes wouldn’t be needed.

You wouldn’t have laws which prevented people from negotiating with employers as a group. So you could let the chips fall where they may. Of course, you also wouldn’t have laws which granted special legal powers and protections to such groups, so the first set of protections aren’t needed. If unions don’t have superpowers and NLRB rulings and special protections, then you don’t need to have special exceptions

but I think you would not support the repeal of all union-related laws. I am certain you recognize that removing those regulations (which is an inherently libertarian thing to do) would probably result in a net decrease in unions; since you are generally pro-union I think you would oppose that.

So you should acknowledge that you’re already a a very non-level playing field right now.

It’s not, really; it’s just that you are starting from a point which doesn’t acknowledge that we’re already far from neutral ground.

In a neutral world, that would be fine. In practice it isn’t a neutral world.

Say that 51% of your colorist employees decide to form a union and demand a closed shop, threatening a strike. Ten of your least favorite employees are the organizers. To put you on notice, your production goes down–not enough to really discipline everyone, but enough to hurt your bottom line.

In an unregulated world, you have the right to look at them and say “screw that. I don’t want a bunch of people working for me who have demonstrated their unhappiness with the job. You’re all fired.”

In the current world, you might be obliged to negotiate with them; you can’t take action against them for forming a union per se; you can’t do a lot of things.

You may think that’s grand, but you must admit: existing laws grant the unions power. Power that they would not otherwise have absent government interference. And because of that government-supplied power, the union can drive a harder bargain than it would if it didn’t have a government sword.

The likelihood of ending up with a “closed shop” deal is larger with government help than without government help. RTW laws are designed to try to balance that: union-power laws make it more likely that a non-union person will get pushed out and RTW laws make it more likely that they can get back in.

Because you’re ignoring where you’re starting.

G&W:

If you reply to me again, I request that you answer this question. Do you acknowledge that RTW laws “mean that union security agreements are prohibited by law, even if workers and the employers want to negotiate such an agreement”? Because if you refuse to acknowledge the plain facts of what RTW laws do, then that’s a point we have to hash out before any other discussion can make any sense.

* * *

I don’t agree with you that the current US laws, taken as a whole, favor unions. Some laws do – firms can no longer just hire thugs to machine-gun workers, to pick the most important example – but on the whole US laws severely restrict union organizing while giving enormous unfair advantages to employers. (And RTW laws are a big part of that.) This is even more true if we consider laws as they’re applied in practice, rather than just on paper, since many so-called “pro-union” rules, like the rule against firing employees for organizing, are enforced only with meaningless wrist-slap fines.

Also, you wrote “The government is already using the force of law to support all sorts of agreements.” Enforcing contracts is required for a market economy to function well; the same isn’t true of prohibiting union security agreements. As I understand it, Libertarianism is not anarchism – libertarians are in favor of minimal laws, not no laws at all. More specifically, libertarians allegedly favor the minimal laws necessary for a market economy to function well. Enforcement of contracts fits into that “minimum necessary” restriction; prohibiting union security agreements does not.

The purpose of the prohibition isn’t to enable market economies to function (as the states without RTW laws demonstrate, markets can function fine without prohibiting union security agreements). Nor, if we’re honest, is the purpose among the wealthy businesses who campaign for RTW laws to help workers. The purpose is to give employers an unfair advantage in negotiations by ruling out a type of contract most employers want to avoid, rather than forcing employers to negotiate concessions in order to avoid those contracts.

Amp,

What’s with the whole “if you reply I request you acknowledge? stuff? This was literally the first (bold) paragraph in my very first post, so I didn’t think I needed to say it again…

So yes, of course that would mean that “union security agreements are prohibited” under RTW.

Before I go down this rabbit hole: as compared to what? This seems so obviously untrue to me that it seems you have to be using the wrong comparator.

I suspect you may be talking about “whether the current US laws, taken as a whole, favor unions such that the overall balance of power rests with unions and not with employers.” But that’s not the right comparator.

The proper comparator is “whether the current US laws, taken as a whole, favor unions as compared to what the status of unions would be without any laws that address unions.” So for example, a law which prevented unions from striking would be an anti-union law; a law which prevented employers from hiring alternates (or firing union organizers) would be a pro-union law.

Ok, what? Again, what default assumptions are you talking about when you say that? To use two multiple choice examples:

a) laws preventing employers from recognizing and negotiating with unions unless they have a certain %age of employee members;

b) no laws relating to %ages.

c) laws requiring employers to recognize and negotiate with unions so long as there are a certain %age of employee members.

and

1) laws forbidding employees from organizing

2) no laws one way or the other relating to either side

3) laws forbidding employers from taking adverse action against organizers.

Which ones would you call “severely restricting?” In my mind that would be (a) and (1), without also having (c) and (3).

For example,

The National Labor Relations Act gives workers the right to:

Attend meetings during non-work time to discuss joining a union

Talk about the union whenever other non-work talk is allowed (including on the job site)

Read and distribute union literature as long as you do this in non-work areas during non-work times such as breaks, lunch hours or before or after work.

If they get a union certified, the employer will be legally required to negotiate in good faith with the union to obtain a written, legally binding contract covering all aspects of employment.

I suppose you could read “severely restricting” to mean “they can’t actually do whatever they want during working hours and still be legally protected from consequences,” or perhaps “they can only obtain government-enforced rights to negotiations if they hold a vote first” but that would really be a linguistic stretch.

There are strike-prohibited bargaining units. So yeah, that’s pretty anti-union. Those employees have to go to binding arbitration if they can’t negotiate the contract they are willing to accept.

Looking at NLRB decisions from the last 20 years, the NLRB is hardly protecting unions-most unfair labor practice charges filed against employers (from the office where I work) during a representation or unit clarification procedure result in little or no damages against the employer *even* when the employer is found to have violated the law.

I think the biggest proof that unions are not specially protected is the decline of private-sector unions. After all, businesses are free to move to RTW states, and some of them have done so (or moved out of the country, even, to avoid the expense of US laws about employee compensation, safety, and protected classes). There are near-constant political attacks on public sector unions (and I thank every one of you open handed conservatives for doing so, as every time you lose, you pay my hourly wage in attorney fees).

I don’t want to go back to dog-eat-dog relations between employers and employees, and that’s what laws and unions prevent. I won’t fight public sector unions even though I think they’re unethical because they at least try to prevent worse ethical problems, like cronyism and nepotism.

Agreements that create closed “union shops” – basically forcing other workers to join the union, rather than negotiate their own deal.

Yes, those kinds of agreements. What about those kinds of agreements is so corrosive and destructive that they must be singled out for prohibition? The argument that Susie may not want to be part of a union, or pay dues, or allow the union to negotiate on her behalf strikes me as a complete nonstarter, because there’s no sensible right to be able to work without any conditions on your employment that you dislike or disagree with (indeed, such a right would make any sort of employer-employee relationship impossible).

Framing this in terms of being “left alone” just doesn’t make sense, because if you want to be left alone, getting a job is a very poor way to go about it.

Since their own services have to do with the functioning of the Government, a strike of public employees manifests nothing less than an intent on their part to prevent or obstruct the operations of Government until their demands are satisfied. Such action, looking toward the paralysis of Government by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.

You’ll be glad to know if you don’t already, RonF, that federal government employees do not have the legal right to strike.

Additionally, teacher walkouts are illegal in 36 states.

(Interestingly, according to the above article, making teacher strikes illegal is supported by both the teacher’s union and the governor in Vermont, but opposed by the school boards.)

I believe that police and firefighters are forbidden from striking pretty much everywhere in the US, and there are other states that restrict the right of some or all of their state employees to strike.

That isn’t proof that they don’t get protections. That is proof that the protections that they have are decreasing. You are confusing relative changes with absolute status.

To use an AA analogy: If some colleges instantly stopped using race as a consideration for admissions, you would see a decrease in admits for black and latino applicants. But that would not “prove” that those colleges were discriminating against blacks and latinos; the change would result from the removal of laws that benefit those classes and not from discrimination.

The changes in union membership are a relative term. Just as employer actions drove the pendulum to the union side, union behavior is driving the pendulum back again. But that doesn’t mean it’s on the employer side. It isn’t.

It seems to me that “Right to Work” laws are essentially civil rights laws. In this context they mean that an employer (or prospective employer) cannot discriminate against you if you refuse to join a union. There are plenty of other anti-discrimination laws on the books that preserve your right to have a job – in general an employer cannot discriminate against you because of your race, your religion, etc. – and, in States with RtW laws, your refusal to join a union.

The only way that the first speaker’s first comment makes sense to me is if he has confused (as those on the left often do, it seems to me) “right” with “entitlement”. You have a right to not be barred from seeking employment for various reasons. However, the laws in general no more entitle you to have a job than the First Amendment entitles you to a free printing press or the Second Amendment entitles you to a free gun – nor, in my opinion, should they.

Closetpuritan, that’s good to hear about Federal employees. But State employees are also public employees, and here in Chicago every fall brings teachers’s strikes in various school districts, and the Chicago Teachers’ Union authorized a strike last year (IIRC) perfectly legally, despite a law setting a high barrier against it.

It seems to me that RTW laws are an impairment of contract-the employer’s right to contract with the union. What about those employers? Supporters of RTW laws don’t seem too concerned about them. My employer, for example, *wants* to be a union shop-it’s part of their firm identity, something that draws clients to them.

This isn’t an issue I have thought deeply about, so these are preliminary thought. It seems to me that Kai is bringing up two arguments for how RTW laws might be considered to infringe on an employer’s freedom of contract. While Kai blends the two together I think it may be helpful to keep them seperate.

First, consider whether RTW laws infringe on an employer’s freedom of contract during negotiations with the union. On this analysis, I think G&W has the better argument: the negotiation between an employer and union is already heavily regulated. Just as freedom of speech includes the freedom not to speak, so too the freedom of contract includes the freedom to walk away. Once the legal framework requires an employer to recognize a union, negotiate in good faith, refrain from firing striking workers and/or go to binding arbitration any change to that framework that limits the scope of the negotiations is a net move towards freedom to contract.

[I am paraphrasing, not quoting G&W so I may have misunderstood his/her arguments]

But Kai then raises the second argument which I haven’t seen earlier in the thread (although I may have missed it):

Under RTW laws, the employer is legally barred from adding union membership as a condition of employment. It’s not just that they can’t contractually bind themselves (via negotiations with the union) to require this as a condition of employment; they can’t even do it voluntarily. In this sense, a RTW law does infringe the employer’s freedom to contract.

So, on the one hand you have employers who would prefer not to contractually bind themselves to only hire union members, but who are required to negotiate in good faith and may agree to this limitation in the context of negotiations that they can’t avoid. On the other hand, you have employers like Kai’s who would happily hire only union members even if their union contract didn’t require this. It’s no wonder to me that our 50 states have close to 50 variations of labor law…

Iri @ 28:

I think one of the more recent examples was Hobby Lobby’s case. There was an uproar that they were imposing religion on their employees by not offering four types of birth control. It was wrong to suggest that the employees find a different job if they did not like the benefits.

-Jut

Because, again, they’re inserted into a system which is already restricted.

If there were fewer union laws in general, then there would be no reason to focus on specifically preventing unions.

So, for example, if you said “let’s eliminate any good faith negotiating requirement; allow employers to refuse to deal with unions and fire union members if they want; and also, as part of that plan, allow employers to choose to negotiate with unions and even to reach closed-shop agreements as part of the contracting process,” then that would make sense.

G&W, I am broadly in agreement with you but I think you missed Kai’s point. For some employers the requirement to negotiate with the union is a restriction in theory only. It’s something the employer would enthusiatically do without any prodding by the government. For those employers RTW operates as a law that restricts their freedom to offer employment contingent on accepting conditions of work (specifically, the condition that a prospective employee join a union or at least pay a fair use fee).

I understand precisely what Kai’s point is: For some employers and employees who would independently choose to transact business, a “no closed shops” rule would interfere with their freedom of contract. That much is pretty obvious; I’m not sure why Kai seems to think it’s a “gotcha” kind of question. (Of course, it isn’t clear how many places would actually do that if they were free to contract for whatever they wanted, since even the places who want it now are making that choice in the context of the existing legislation. But it would certainly be a non-zero number.)

But you cannot simply pick that piece out of the soup and act like it’s the main dish. It’s like saying “look, this is a potato–you said it was chowder, not potatoes!”

Non-straw RTW folks would happily grant a free market and a free right to contract, even if that included the theoretical right to create a closed shop. They would recognize that the overall effect of that move would be to reduce unions, which they don’t like.

In all seriousness, do any of the pro-union folks here want to assert that if we removed all laws and regulations pertaining to unions (no NLRB; no requirements to negotiate; no requirements to recognize; no restrictions on negotiations; etc.) union power and membership would NOT DECREASE? IOW, that the laws have an overall transfer of power/bargaining to unions, just as other laws transfer some power/bargaining to employees?

Anyone?

Because having gotten a lot of the “G&W needs to admit” stuff here I see a very small # of people admitting that pretty basic fact. I think most of us would admit that those laws are in place for a reason, and the reason is “protecting the power and influence of employee bargaining groups,” at least to some extent.

Kai Jones @ 40:

That is true about so much of the laws surrounding employment. Minimum wage laws are an impairment. The inability to hire an immigrant who has no work authorization is an impairment. (Brief side rant: how far down the rabbit hole have we gone when we accept the notion that someone needs to have the government’s permission in order to work?!) Child labor laws are sort of an impairment, except that we don’t think minors can really contract with anyone in the first place (a bit vague; void v. voidable). Civil rights laws aree an impairment. Overtime laws are an impairment.

This is nothing new.

-Jut

@gin-and-whiskey:

I don’t, you’re projecting. I’m not trying to *get* anybody, I’m participating in a conversation. It’s just another thought I had. Contracts in Oregon are more strongly protected by both the state constitution and appellate opinion than federal contract law; it comes up a lot in my work–that’s why I think about impairment of contract, it’s a big issue here.

I get why you keep saying “unions” instead of “employees,” but it is the employees, after all, whose rights are protected by the laws. Not the unions-the unions are what the employees chose as representatives in bargaining. The laws protect the rights of employees even against the unions, when employees need them to-for example, when employees want to change to a different union, or to decertify the union as their bargaining agent. And employees have the right to sue the union for failure to represent if they think the union didn’t, for example, pursue their grievance hard enough.

It’s not as if there aren’t employment contracts that don’t include a union: there are lots of contract employees out there, who have individually negotiated their contracts, or who use an individual agent (e.g., the local TV weather guy has his own employment contract that is not negotiated through a union).