Recent events at a blog that rhymes with Shmetal-Moptimized reminded me of the existence of sociobiology and of people who imagine that human beings – and ants and bonobos and every other species — are driven primarily by biological imperatives, meaning the things you have to do to stay alive and shove your genes down the road a piece. As you might expect, the “staying alive” part gets short shrift (which is too bad, really) and the “my genes!” part gets rather long shrift (also too bad). The people who discuss these things are busy swapping propositions like “women are irrational because they don’t need to use their brains for anything but mate selection” and “men are better at spatial reasoning because they stalked gazelles through gazelle-mazes in ancient forests, even before the creation of dodecahedral dice” and “unattended male horniness leads to suicidality at the prospect of gene extinction, so the empathetic liberal, if rational, would vote for sex stamps as well as food stamps (both to be humane in the face of sex-having inequality and to cut down on hypothetical lifesaving rape).”

I knew this stuff was out there, but I…well, I don’t often pay attention to loony-tunes philosophizing that has more to do with “logical” constructs of human behavior than it does with (a) watching how people behave and (b) getting knocked around in the world long enough to have some understanding of why they do that. It’s not that there’s nothing to sociobiology. Its father, E.O. Wilson, has always struck me as a graceful writer despite his being so singlemindedly gaga over his science; he, like soft-machine man Rodney Brooks, is right that we are only stuff, and his famous book on the biological basis of ant-society behavior is beautiful, illustrations and all. It is unquestionably true that we build our societies with our sizes and lifespans and circadian rhythms and digestive systems and bipedality and stereoscopic vision and sexual reproduction as controlling factors, along with a host of other controlling factors, cultural, geographic, economic, you name it.

But as a primary explanation for who takes whom to bed, and when, and why, which is how these biological-imperative guys use it… I wonder why these guys don’t see that it’s dumb, what they missed along the way. It’s dumb for lots of reasons, not least of which is that even if you know what you’re talking about (and you won’t), it’s on the wrong level: it’s as dumb as trying to explain your divorce in terms of your husband’s biochemistry (which even Dawkins would say is stupidly reductive), only you’ve flipped the dumbth from the very tiny to the very big side of biology, population-scale biology. Both ignore the scale that involves lying naked next to your husband and listening to him say appalling things about his last-boss-but-one, again, and then watching him pick his nose like an eight-year-old, and realizing you’re going to divorce him, even though at that very moment you have no idea how, and life after marriage is a blank, in your imagination, nothing there at all.

It’s freedoms on that level, not the inhumanly tiny or the inhumanly large, which keep lawyers in business. That you’re lying down, that you’re naked with a man you recently had sex with, that he has a nose to pick and wants to pick it, that the room is heated to 69 degrees Fahrenheit and has a window facing west, all of this finds reason in the way that humans are made. That you married, that you’re married to this man, that you know this is temporary, that there is or is not a child to fight over, that you will simply move into a comfortable if anonymous rented condo that suits your salary, that you’ll work as an accountant for a military contractor involved in the development of a new generation of nuclear weaponry, all of this belongs to decisions taken by you and millions of others, living and dead, within the wide, wide field granted by the human genome, as far as anybody knows.

2.

When I went to college, the first thing I did with my new freedom was to abandon circadian rhythms altogether. I was up, sometimes, roaming the dormitory halls at 3 am, watching Madonna in the abandoned lounges, eating cold pizza, making 15-foot timelines of history (it felt edifying). I also had an 8 am economics lecture in a very large, very comfortable lecture hall, with a professor who was a deeply good guy and hella monotone. So I’d drag my ass out of bed and go to the lecture hall and promptly fall asleep. After a few weeks of this I figured that if I were smart, I’d sleep in bed. So I stopped going to the lectures and read the textbook, and when the midterm came around I got a C-minus. Instead of keeping saner hours and going back to class, I found the basement VAX, which was loaded with a question bank of 1500 multiple-choice items that went with the old Samuelson economics textbook and its imaginary society of rational men.

That was a lot of paragraphs. C’mon ‘n dance.

These were well-written questions, and – long before this was standard practice – each wrong answer came with an explanation of why the answer was wrong. And I had three solid weeks of an extraordinarily beautiful intellectual-air-castle-building experience, in that basement, by myself. I did not go to other classes. I went through the entire question bank, then went through it again, finding that I understood the wrong-answer explanations much better the second time through. It remains one of the loveliest times of my life: such a lucid and coherent system with which to understand the world. I had not known any such thing existed. I emerged from the basement, cicadalike, and went and took the final, and got the top score against however many hundred kids were taking the course. After which the professor came to talk to me and tried to woo me to his department. I didn’t wanna. And he pressed me, wanted to know why. I was still in the grip of economic loveliness, so it gave me a twinge when I shot from the hip with a polite and embarrassed, “It just doesn’t seem to have much to do with how people actually behave.”

“Oh! well,” he said, “it’s just a model.” This made me uneasy; I didn’t know what a model was, but I suspect it wasn’t a good answer, and that it hadn’t really answered my criticism. So I didn’t join up, and as it happened, about 20 years later a lot of young economists came along and said that this rational-actor model had little to do with how people actually behave. I don’t know, but if I had to bet, I’d bet they’ve built new models that also don’t have much to do with how people actually behave.

That’s not a wrong-level problem. That’s about ignorance, failing to understand what’s actually happening, how people really do, possibly because you’re trying your damnedest to systematize it rather than building a library of human experience. No slur against Wilson (or Dawkins, whose Selfish Gene and Blind Watchmaker I enjoy immensely, and who has an ear of purest tin for the non-proteinaceous things humans have: poetry, religion, various forms of unreason, tact), but I am not surprised that sociobiology looks silly to me on any level as a guiding moral philosophy. The Ants is a pleasure to read and sounds authoritative; and yet so much of what Wilson managed to say about people was so silly, even though he’d actually been one of those (you could always head straight for his head-scratching about the improbable persistence of the “homosexual gene”), that I suspect I’d be embarrassed, talking about his ant book’s pronouncements with any intelligent ant.

3.

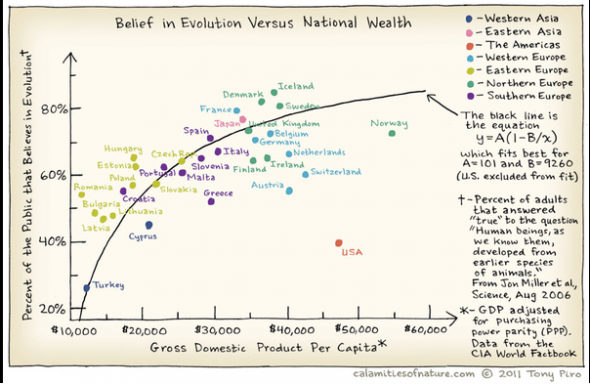

After reading conversation from the Shmetal-blog until the penny dropped and I understood that all these very bright people were talking about Darwin and Wilson, I went (against better judgment) wandering around discussions of “Darwinian feminism” and evolutionary psychology, and to these darker recesses of the internet where boys and men gather to drink sociobiology moonshine and discuss what women want and why, and why they themselves don’t get more sex and respect, and lament the sorry state of the world, what with the dearth of sex and respect. I wanted to remind myself of what was there – I say “remind” because all this business was slugged out by Wilson and (pdf warning) Stephen Jay Gould and a handful of others decades ago — and see if anything was new. There is a sameness to the language in these places and a cultish certainty, now – you can find it wherever these guys talk about “taking the red pill” and “high-status males” and “the sexual marketplace” and other such things. Which reminded me of a graph I’d seen recently, purporting to show that Americans are alone amongst the wealthy in being bible-thumping freaks who don’t believe evolution is a real thing.

So apparently we have that, and on the other side, we have a whole lot of boys and men, some very bright and some dumb as rocks, who believe fervently that evolution is a real thing, and that it’s evolved men and women to be like it says they should be in the Bible, more or less, assuming you don’t actually read the Bible like us Hebrews do. (Incidentally, there’s a perfectly bitchin painting of Judith with the head of Holofernes in the Met. This girl’s wearing some sharp threads, and there she is grasping this big shaggy head by the hair anyhow, looking like she’s trying to make it uptown by five to deliver a check to a realtor and nab that co-op, after which she’ll get back to teach her class at Hunter. You should see it. But I digress.)

The first thing I thought was how many young men are out there with absolutely no idea what men and women actually are, how we do, what we want, why. No vision whatsoever of the tremendous and weird diversity of desires, misconceptions, half-baked plans, tastes. And instead they sit and warm themselves at the fire of this terribly impoverished construct of what life is and how to win at it before one becomes biologically irrelevant at the age of 30 or whatever it is. In place of observation and description come rules, and rules, and more rules, based on ideas of what should be (for them), what’s fair (for them), what’s rational (given so little information or inclination to go get more), until it’s like some kind of wilderness scholasticism, out where the truly crazy ideas grow.

I thought about that, and about religiosity, and about that dormitory lounge, again, where I also watched a very young Ralph Reed, and thought he looked like trouble, and then suddenly I thought about the letters collections I’d read long ago, the New York stories of the modernists. All those young artists and writers who’d left their hometowns for little apartments in New York, running away to the city, where the minds weren’t so small, back in the 1940s and ‘50s and ‘60s. And I thought: Have we come here again, do the young people have to run away to the city. And I thought about David Owen’s book about how ecologically New Yorkers live, how the city had long been scorned as a den of iniquity and disease because it was filthy, but that this was wrongheaded; and I thought, well, that analysis is, a bit, too. The city’s a den of iniquity not just because of horseshit in the streets and graft and bus exhaust and unfiltered cigarettes and garbage strikes and litter, but because it has the hopheads and the career gals and godless atheists and the freaks and the fags and all that. Which is also why it’s the place to be, demonstrably more fun and richer, if you pay attention to what mathematicians say. (Actually they just point the aggregation of people, and the correlations amongst city size and interesting things to do and average salaries.)

And then I thought how most of these young men talking about red pills around the campfire must, at some point, recognize that they were talking like damn fools. How after six or ten angry years they’ll meet some woman and after a while, after living with a real live woman whom they respect, and meeting (surprise!) some other grown women they respect, admit that they had some extreme views, and after a while longer admit that all that jack about beta males and sluts and peak fertility made very little sense at all. And be embarrassed by the whole business if forced to relive those days. But I wonder how much damage they must do to the women they meet and maltreat in the meantime. I doubt very much they’ll want to think about that.

A book they’re unlikely to read is T.H. White’s The Book of Merlyn. It’s the last book of The Once and Future King, about the unprepossessing boy Arthur who must become a reluctant King. Now he is a very old man whose heart is long since broken, and yet he must still rule a kingdom on the verge of insurrection: his bastard son has marshaled a fascist army against him. His old tutor, Merlyn, has brought him back to the animals who were his first teachers and friends, to try to put life back into him, and – as in boyhood– he is taught to think about human society by being turned into other animals – an ant, a goose — and forced to live amongst them, study and observe, and be rescued at the last minute, or ripped away from a happy private life and love in the guise of that species. It is all very closely observed, and extremely humane; and in the novelist’s, rather than the academic’s, fashion, the knowledge comes from living it yourself, with teachers nearby who are ready to tell you that while your experience is real, your conclusions could not be more stupid. This is a political book, written during the Second World War (over a decade before the young E.O. Wilson would write his doctoral thesis at Harvard, on ant taxonomy; over two decades before the triplet code was cracked), and Arthur is being given a cram session in political economy: the communist totalitarianism of the ants, the communitarian anarchy of the geese. As cruel as the lessons are – he must live them, after all – and as tired as he is, he comes to the point of understanding what he must go back to work for and why, gathers himself, and goes out to do the work of making peace.

It goes as well as anyone with a taste for reality might expect: there’s a misunderstanding at a bad moment; his peace fails, and the old man is killed in a scene of anguish and brutality. It’s a curious thing about the violence: it’s not about a universal aggressive bid to pass on the genes and die, or to take over territory so as to spread tribal seed and exclude the other, or for any reason, except that the young species man – alone amongst the animals — is breathtakingly stupid, arrogant, and destructive, redeemed only, perhaps, by getting on well with dogs. Despite all the careful study of other species, their bodies, and how their bodies affect their behavior and their treatment of each other – all of which looks sociobiological — there is actually very little in the way of biological imperative in the story about men and their wars. The nearest it comes is at the end, when Arthur holds his last Privy Council with the animals, and Merlyn, earnest scholar, advises him for the last time on the pros and cons of war, waxing sociobiological about why ants fight and the adrenal requirements of man. To which Arthur responds: “We were told that war is caused by National Property; now we are told it is due to a gland.” But he is old and scarred enough to know that it doesn’t matter.

The things Arthur sought to preserve were not genes, not bloodlines, not even land, but what he had learned from other peoples, by experience, about how his own might live well and peaceably. And failed, but not so thoroughly that no wise man could try again, despite our unfortunate natures; perhaps someday we might grow up. This, it seems to me, is by far the more promising story.

What a beautiful post to come to Alas with. Welcome.

There is a moral lesson in The Once and Future King that has always been my favorite. I’m paraphrasing from memory, so I’m sure I don’t have it exactly right, but there’s a bit where Arthur and Merlin are talking about whether war is ever justified:

Merlin: “Well, war’s justified if you’re defending yourself, like if the other fellow started it and you have to go to war in defense.”

Arthur: “But Merlin … everyone always says the other fellow started it!”

Merlin: “Yes, they do. And that’s a good thing, because it shows that on some level, they know that what they’re doing is wrong.”

It’s one of the most hopeful things I’ve read about humanity, both that exchange and the book in general.

—Myca

Thank you, Myca. I’ve been reading his books for about 30 years now, and there’s still stuff that’s news. I was surprised last year by how well The Master holds up well, too – an old favorite, but much in there’s so anachronistic I thought it might not play. My daughter loved it anyway, until it got too scary.

Wow. That is one fantastic post. I suspect that I’ll read it again and again just for the writing. Sure, sure, the subject is awesome, too and reinforces my beliefs so, of course, I love that… but the language!

thank you for this wonderful essay! The Book of Merlyn is such an important work.

Oh, I liked Unweaving the Rainbow very well. The trick appears to be that I read it in German translation. I’m told that in the original Dawkins made various failed attempts at waxing lyrical himself; the translation lacks them all.

This reminds me so very much of Terry Pratchett’s refrain — the problem with human society isn’t this belief system or that political system but always comes down to people being people, and so the ideologues’ solution is to get rid of them and replace them with better, more “rational” humans instead of dealing with people as they — strike that, that usage is part of the problem right there! — as we are.

It’s a very Procrustean mindset the misusers of science have, just lop off the bits of reality that don’t match up to our model and that will fix the world…the same mindset that sets up traffic patterns in schools that don’t work and tries to keep the students from walking on the grass with increasingly draconian rules and punishments instead of, you know, putting a pavement where people actually need to go, or beating babies with a rubber hose (“plumbing line”) whenever they cry and fuss — although the skeptical Red Pillers would be horrified to be compared to the likes of Michael Pearl and his “biblical parenting” methods, I’m sure.

(And there’s something very ironic in the MRA appropriation of The Matrix “red pill” imagery for their delusional belief system!)

Simply an outstanding essay, in my humble estimation. You managed to pull off the difficult balancing-act between playfulness and insight with aplomb.

I came here from Pharyngula and I’m so glad I did. This is beautifully and entertainingly written. It made me laugh out loud and also think deeply.

I read the original Once And Future King (without the Book Of Merlyn) many years ago, loved it and gave it away. I’ve just acquired the complete version to lend to a friend who is intrigued by all the references to it in H Is For Hawk. Looking forward to re-reading it.

Superb.

*wild applause*

Wow,

I don’t think I’ve ever known anyone else who has read the Book of Merlyn! This book had a subtle influence on me as a young man studying biology in the ’70’s. I understand that the unpublished manuscript of the tongue in cheek last chapter of the Once and Future King, was found in TH White’s office and published after his death as the Book of Merlyn.

You may recall the sign over the entrance to the ant hill where, “Everything not forbidden is compulsory”.

I echo David Evans above “This is beautifully and entertainingly written. It made me laugh out loud and also think deeply.” I look forward to reading some of your other posts.

To David I suggest also reading “The Crystal Cave” by Mary Stewart. It’s the life of Merlyn.

I’ve finally had a chance to read this. Wonderfully done, and it is, indeed, a lovely piece of writing. Welcome to Alas.

Thank you, Richard (and thank you to everyone else who said such kind things and/or commented thoughtfully). I’ll have a little about-me post up soon.

Beautiful post. Thanks for writing it.

I think experience vs conclusions is a big aspect of that particular discussion. There rarely seems to be an honest “your experience is real and I feel your pain” among most of those who want to teach these men to draw different conclusions”, and I think a large part of that lack is not of lacking experience, but rather of – different – conclusions.