Help me make more cartoons by supporting my Patreon! A $1 or $2 pledge really matters to me. I usually post cartoons on the Patreon weeks or even months before posting them here.

I’m sure we’ve all had the experience of arguing with someone about politics, and it becomes obvious that they’re not actually responding to, or truly listening to, anything you’re saying; they’re just using what you say as cues for the already formed arguments they’re eager to use.

Obviously, that experience inspired this cartoon. I can’t even tell you the number of times I’ve seen people criticize or mock the slogan “believe women” by pretending it’s a slogan about courtroom standards and getting rid of due process – which it obviously is not. I wouldn’t say no feminist has ever used it that way – there are, after all, millions of feminists – but it’s definitely not the common usage, and pretending it is is just so intellectually dishonest and I GET SO FRUSTRATED AND

…And hence, this cartoon. I hope you like it!

I’m not sure I’ve ever used the word “hence” in a sentence before.

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

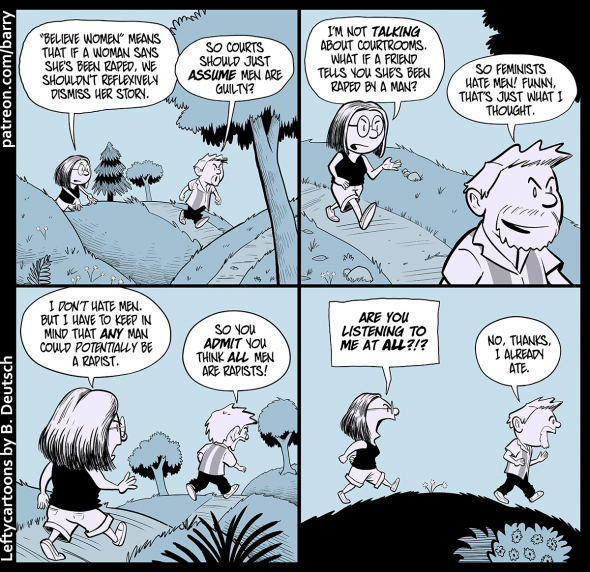

This cartoon has four panels. Each panel shows the same thing: A man and woman walking through a hilly park – not side by side, but with him ten feet or so ahead of her. There are shrubs and trees and little pedestrian paths through the grassy hills. She is wearing big round glasses (“big round glasses: the cartoonist’s best friend”), shorts, and a black tank top. He has a beard, and is wearing a bowling shirt with two thick vertical stripes, and black pants.

PANEL 1

GLASSES is talking and making an “I’m just explaining things here” gesture, with her palms held out in front of her. BEARDY is looking grumpy as he talks back.

GLASSES: “Believe women” means that if a woman says she’s been raped, we shouldn’t reflexively dismiss her story.

BEARDY: So courts should just assume men are guilty?

PANEL 2

Glasses looks a little annoyed, putting one hand on her hip. Beardy is smirking.

GLASSES: I’m not talking about courtrooms. What if a friend tells you she’s been raped by a man?

BEARDY: So feminists hate men! Funny, that’s just what I thought.

PANEL 3

Glasses looks even grumpier; Beardo is raising his voice a bit.

GLASSES: I don’t hate men. But I have to keep in mind that any man could potentially be a rapist.

BEARDY: So you admit you think all men are rapists!

PANEL 4

Glasses is now shouting, her hands balled into fists. Beardo looks positively cheerful.

GLASSES: Are you listening to me at all?!?

BEARDY: No, thanks, I already ate.

OK, then, how should we handle a case like Tara Reade’s? She claimed to have been raped by Biden. Some feminists called for him to withdraw from the race. Then it turned out that there was no “alcove” in the part of the building where she claimed to have been raped and that she had lied about her credentials as an expert witness in a criminal trial and exaggerated a story about an ex being a suspected serial killer (he was one of dozens of people questioned and they found the real guy a few weeks later.) So how does “believe women” apply in a case like this? (Keep in mind that if the Democrats had dropped Biden, the Republicans would have definitely made an issue of it when the questions about Reade’s credibility appeared.)

I think that *some* feminists are particularly bad at parsing cases based on anything other than the party affiliations of the people involved.

Tara Reade’s accusation was, on face value, serious and possible, and it took a while for the story to go through the phases it did before we eventually landed on, “This probably didn’t happen.”

So it’s important to remember that the response was not monolithic, and it changed over time. At the beginning, there were, obviously, some people that immediately without evidence discounted Reade’s allegation, but there were also people who said variations of “I believe Reade…. But I’m going to vote for Biden anyway”, and there were some people who immediately said that Biden needed to go.

My observation, as an outsider looking in, is that messages like “Believe all Women” suffer in two ways:

First, They almost invariably pick up semantic overload. As much as most feminists might understand “Believe all Women” to be a baseline position that women’s accusations should not be immediately discounted (something I agree with completely), there are examples of times when some feminists have failed to apply that standard (Reade is an example) and there are other examples where some feminists took that standard and ran with it to places that shouldn’t have applied (Kavanaugh, at some point). It becomes obvious that there’s something more baked into the term than merely the baseline assertion, at least for some people. If someone disagrees with that and would like to explain to me the dichotomy in response from Democrats between the Ford and Reade allegations, I think I’d like to have that discussion.

Second, once the term makes it to the secondary market, regardless of whether semantic overload is present or not, it’s interpreted in the worst possible context by people that think they’re ideologically opposed to the speaker. This is common to the point of near certainty, and while I think that there are terms that almost seem designed to be misinterpreted (toxic masculinity), I don’t think that we need to re-evaluate the terms, because regardless of what certain things are called, they’ll always be misinterpreted, because the point is to misinterpret.

Both problems lead to an exhausting cycle where you’re forced to defend your position against the strawmen arranged in front of you, and the people you’re engaging with probably aren’t going to change their mind. You have to decide whether you’re doing this as a mental exercise, or if you’re trying to persuade the audience, or if you just need to remove yourself because the conversation isn’t going anywhere. It’s not fun.

Michael – it applies by not assuming from the get-go that she’s lying just because she’s a woman disclosing a sexual assault. Not reflexively assuming that a woman disclosing a sexual assault is lying does not mean that we stop using rational thought. It means that allegations of sexual assault get investigated as though they are credible until they turn out not to be. You know, the way we treat other criminal allegations.

I’m already wondering about the title: “Hush, woman …”

Are men really allowed to say that today?

LOL

“any man could potentially be a rapist”

19 results

“all men are potential rapists”

25 500 results

“all men are rapists”

348 000 results

Hmmm

Polaris:

I didn’t use the term in this cartoon, but one catchphrase that means “any man could potentially be a rapist” is “Schrodinger’s rapist,” which yields 53,000 results.

Searching for “potential rapists” gets 128,000 results; skimming the first few pages, most of those results are people using variations of “any man could potentially be a rapist” (e.g., all men are potential rapists, viewing men as potential rapists, etc) that wouldn’t have shown up on your search. Many of those results are hedged in some way (like this, from the first page of results: “…Obviously, this is not saying and should not be interpreted to mean that 100% of men rape.”)

But I should admit, many are saying variations of “not all men are potential rapists,” which makes interpreting these results dicey.

Speaking of the “not” problem with this sort of search: Searching for the string “all men are rapists” gets 152,000 results, when I tried it just now. (Google results are often inconsistent.) But looking through the results, I noticed that many of those search results included the word “not,” as in “not all men are rapists,” and when I searched for that string, I got 134,000 results.

Many of the other results were people quoting a 1977 novel. (Some of those are anti-feminists not clarifying that they’re quoting a fictional character.) Inferring how common beliefs are from search results for a famous quote seems dubious; I got 590,000 results for the string “I see dead people,” but all that means is that it’s a famous quote, not that everyone who wrote that on a webpage believes they’re seeing ghosts.

“Hmmmm,” as you used it, seems to be you implying something but not wanting to actually say it. I’ll ask you straight-out: Do you believe that far more feminists believe that all men have committed literal rape, than believe that any man could potentially be a rapist?

My point is that the difference between could be and are is not a small one.

Also I’m speaking of the narrative.

@6

Is there a reason those terms are talked about? (“any man could potentially be a rapist” or “Schrodinger’s rapist”) They seem like truisms; Sure, any man could be a rapist, but any person could be a serial killer, every motorist could swerve into your lane. But we don’t often consider those possibilities because the likelihood that a person is a rapist, murderer, or really bad driver is relatively low. Seeing half of humanity as a potential predator seems like a really rough way to navigate life, to put it mildly.

The chances of a man being a serial rapist are much, much higher than the chance of him being serial killer*. The summary at the link looks at two studies. Both are seriously flawed, in that they only look at male perpetrators and female victims. However, they give a sense of the magnitude of threat women face from men. To put it quite bluntly, if you’re at a party with 25 men, chances are good that one or two of them are serial rapists.

No shit? Really? You think?

*The two studies I link to would give a figure of 6.5-13 million serial rapists in the U.S., compared to 2,743 serial killers.

Yes to what Kate said.

The original point of “Schrodinger’s Rapist” was to give straight men advice on when it’s inappropriate to try and strike up conversations with female strangers.

The chances that I know some rapists is close to 100%. The chances that I know a serial killer is close to zero. So I don’t think they’re comparable. (As Kate said.)

In addition to the threat of rape, there’s also street harassment – and I think a lot of men underestimate just how threatening street harassment gets. (Relevant cartoon).

Corso:

It’s nice to hear that acknowledged, if you’re expressing sympathy for the half of humanity (roughly) who find ourselves in this position, and not suggesting that the fix is to just stop being aware of the threat level and welcome all men as perfectly safe until proven otherwise. A lot of men think that the fix is to stop being so paranoid. Which is why a lot of people feel obliged to point out the numbers in an effort to explain that it’s not paranoia, it’s a day ending in ‘y’.

Grace

I know for sure I know people who’ve raped someone because I’m aware of the rape.

I also have a friend who realized some of his behavior had fallen under the assault umbrella and subsequently undertook the necessary emotional and cognitive work to never do it again.

It’s just a thing. If you know people, you know people who’ve done stuff.

I remember going through this on the blogosphere with the question of “do you know s9meone who’s BEEN raped?” And lots of people were sure they didn’t because no one ever walked up and told them about the guy who pinned them down when they were in high school so they stopped saying no because he kept getting more violent. I mean, even if people did share traumas all the time, which they don’t, not every thing that happens to someone in their entire lives is going to come up in conversation.

I feel like it’s a necessary and sometimes painful part of becoming an adult. You realize there’s lots of stuff going on under the surface of the world.

“Believe women” should mean “believe women at the same rate and with the same respect as you believe people about other things.” That’s what it originally meant, I believe, and that’s what ime most people mean when using it. But a lot of people are Goddamn shitty about nuance. Slogans meant to be shorthand become perceived as truths, either by people propounding them in ignorance, or people misapprehensing them as in this cartoon. It’s a political danger of shorthand and I don’t know how to deal with it; I’m beginning to think it’s just an inherent function of how we communicate in a broader western context (possibly further, but I can’t speak for cultures everywhere).

People should also, IMO, be able to practice situational belief — which is to say an acknowledgment that we don’t know, and usually can’t know, almost anything with ironclad certainty. You can know almost certainly, but I think most of us have had the experience of something we were sure of turning out to be wrong. How often does a seemingly happy family turn out to have a drunken abuser in it? How sure were you it was happy before you knew that? And yet it would be inappropriate to act as though a family you had genuinely no reason to suspect was definitely harboring an abuser. One must make peace with uncertainty—and in uncertainty, one must act as well as one can on the information one has DEPENDING ON CONTEXT. A therapy group is not a social conversation is not a professional organizations ethics board hearing is not a court room.

Believe women about assault. As you believe other people about other things. Realize your belief in uncertain. And allow it to influence your behavior in different ways in diffferent contexts, as appropriate to those contexts.

@11

I think I started this conversation believing the latter, and now it’s the former. A part of me chafes at the idea that women might treat me as a potential rapist, but if ten percent of men are admitted rapists, give or take, I don’t know what else they can do. I’m not about to start playing Russian roulette either.

Corso – Thank you for being open to changing your mind.

Mandolin –

This is such a great comment. “Situational belief” in particular is something I’ve often thought about without having a word for it.

Thank-you for listening, Corso.

Thank-you for your excellent comment @12 Mandolin.

“Believe women” is like “defund the police” or “decolonize XYZ” – it’s a maximalist position repeated to show one’s seriousness about an issue, not an actual demand.

When you drill down on any of those statements as policy prescriptions, almost any defender will backpedal and caveat while attacking you for bad faith because everyone knows they obviously don’t really mean what they mean. This springs from the idea that there is an unwritten code of manners that says treating certain social justice tentpole slogans so literally you actually consider negative consequences is a sign of bad faith. So it’s really an in-group out-group signal thing.

LTL, you could say the same thing about a slogan like “pro life.” And, honestly, although it depends on the exact context of the argument, in most instances arguments like “they’re not really pro-life, since they’re not against the death penalty” are a similar problem.

I think it’s bad faith, in many cases, because even AFTER explaining what something like “believe women” means, people don’t alter their “so you’re saying that we should just throw men in prison with no due process” arguments. Or if someone has argued on this issue many many times before and knows very well that “believe women” doesn’t mean that. After a certain point, people are refusing to account for what a slogan means, not because they haven’t had a chance to learn, but because there’s a tactical advantage to refusing to learn. Or because they’re simply so deep inside a bubble that they can’t credit anything but the very worse narratives they’ve heard. Those are the sorts of things this cartoon is about.

“[W]e must recognize our ignorance and leave room for doubt. Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty – some most unsure, some nearly sure, but none absolutely certain. Now, we scientists are used to this, and we take it for granted that it is perfectly consistent to be unsure, that it is possible to live and not know. But I don’t know whether everyone realizes this is true.”

Richard Feynman, “The Value of Science,” address to the National Academy of Sciences (Autumn 1955)

“Doubt may be an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is an absurd one.”

Voltaire, Complete Works of Voltaire, Volume 12, Part 1

“Stupidity consists in wanting to reach conclusions.”

Gustave Flaubert

I struggle with this one. Should I have a different standard of belief depending on context? Or should I simply have a different standard of behavior depending on context (E.g., exhibiting greater sympathy in a counseling session than in a jury room)?

My wife liked to bolster her arguments by telling people that I shared her point of view. I suspect she gained that impression about my beliefs because I tried to act sympathetically as she discussed her day. But, when pressed by others, I would acknowledge where my views differed from hers. Later (and privately), she would express frustration that I had failed to loyally back her side of an argument. And I would express frustration that she would presume to know my point of view without asking me. She has largely discontinued this practice.

But when disciplining kids, I would pretty much back her up regardless of what she said about my beliefs. Her practice still frustrated me, but in those contexts I had a more pressing objective than candor and accuracy. I didn’t modify my beliefs, merely my actions. But upon reflection, I wonder if perhaps I should have subordinated my concerns for candor and accuracy in the earlier context as well.

It’s a reduction of long ideas to short ones thing. It’s not in any way unique to social justice tentpoles, If you were suggesting so. It’s the whole mishegas behind sound bite politics, behind sloganeering. It’s not in any way owned by any group.

It happens with writing advice (“show don’t tell” aggggggh). It happens with science (Birds aren’t exactly dinosaurs). It happens with health advice (“exercise more,” while repeated often, is not actually meant to apply to people who have medical conditions that make them unable to do so, or who already exercise at maximum physical capacity). I could go on.

Things are complicated. Language and time are limited. Catch phrases emerge. Drives me absolutely up the wall. But what can you do?

Hell, much as lazy expression bugs me, it’s just part of a spectrum we can’t escape. It’s impossible to communicate without approximation.

Nobody,

Eh, belief/behavior, probably different for everyone. Behavior is the important bit.

I do feel like I practice something like belief In different contexts depending on what’s appropriate. For instance, I don’t believe in, e.g., nature spirits if I’m thinking about and articulating my serious view of the nature of the universe in a concrete way. But I’m happy to foreground the part of myself with suspended disbelief when I’m talking to someone who’s excited about cool stuff they believe. More than happy – it’s an important experience for me.

For me, what I’m doing is probably a mix of anthropology stuff (about relativism, participant observation, the attempt to come to things while aware of ones biases, etc. ) and the kind of method acting ish stuff I Stole from stage practice to use as a writer (where I attempt to immerse in someone else’s emotional mindset and belief system).

Eh. People adopt slogans for rhetorical advantage. I feel no duty to cooperate in that endeavor. I understand the slogan “pro-life” to seek to elicit sympathy based on a common appeal to things that threaten life. I see no problem with noting the incongruity/hypocrisy when people who seek to make such appeals fail to act consistently with them. If people want to discuss using the power of the state to seek to limit access to abortion, they can do so without relying on rhetorical tricks.

That said, I acknowledge strategic reasons to refrain from focusing on rhetoric to the exclusion of other points. Rhetorical arguments generally won’t hold people’s interest for very long–including mine. And they may simply impede the flow of discussion.

Just a side note, but lots of people are against abortion and against the death penalty. The phrase “pro life” applies without qualification to them.

Why Amp will never be Santa Claus:

Charlie: Dad, it [graffiti] doesn’t come off.

Dad: It’s not supposed to come off. Hence you’ve got to be careful where you put it. Hence tagging is serious. Hence your presence here.

Charlie: Don’t say “hence” any more, Dad. It’s really annoying.

The Santa Clause 2 (2002)

“Believe women to the same extent you would believe a man” is not actually a great strategy, at least in the area of rape accusations and sexual abuse (where it is most frequently encountered). When it comes to rape survivors, men who accuse other men of rape are disbelieved, mocked, victim-blamed and ignored just as often as women are. I am pretty certain that many of the the people engaged in both active and passive suppression of rape against women would behave exactly the same way when dealing with rape against men, and often have. So they are in fact treating the genders equally. Not well, but equally.

Of course it’s true that treating rape victims poorly is in fact an anti-female approach because most rape victims are female. But it isn’t an inequality addressed by asking people to equalise their treatment of women survivors as a group with male survivors as a group.

So if “believe women” is really intended to mean “believe women to the same extent you believe men”, I think it’s not actually that useful, even if it isn’t unequal.