This cartoon is another collab between me and Becky Hawkins.

If you like these cartoons then these cartoons like you too. They sit up at night thinking about you, but not in a creepy way. But they do it all the time, and that is a little bit creepy. Thinking… thinking… thinking… Maybe if you supported them they’d stop? But when I put it that way it sounds a bit like blackmail. Um, never mind.

A reader emailed me a while ago to say that he really appreciated the cartoons I’ve done about disability issues – about ableism, really. (And that was striking to me, because at that time I think I’d done only a few cartoons about ableism, plus another couple that touched briefly on it.)

(I haven‘t done many more since then, alas. You can see all of them at this link, if you’re curious.)

The reader, who identified himself as autistic, mentioned that he’d really like to read a cartoon by me focusing on issues experienced by autistic people. I said what I always say when I get requests like that – ”That could be a really good idea for a cartoon, but I can’t control where my inspiration goes. But I’ll see if an idea comes up.”

For me, inspiration often comes from listening to people complain. So I began listening, both by lurking on relevant public forums, and by talking to some of the autistic people I know. Some complaints about things neurotypical people say to or about autistic people waaaaay too often began occurring again and again, and presto: A comic strip. (Honestly, there was enough material for two comic strips, so you may see a sequel someday).

Once this strip is public, I’ll search through my email and try to find the person who wrote me, so I can point the strip out to them. I hope they’ll be pleased. (Defaulting to “they” because I don’t remember what pronouns they prefer.)

I was planning to draw this one myself, but Becky saw it in my scripts folder and asked if she could do it, because (she said) drawing eight jerks would be fun. I couldn’t argue with that logic! And she did her usual great job. I especially like the way she used limited color this time (because I love comics done with limited color, as I’m sure many readers have noticed).

It was Becky’s idea to have the “Have you tried Yoga” character go on and on and on and on, appearing against a background of endless words. I loved that idea, and I love Becky’s drawing in that panel – all that chunky jewelry looks great.

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

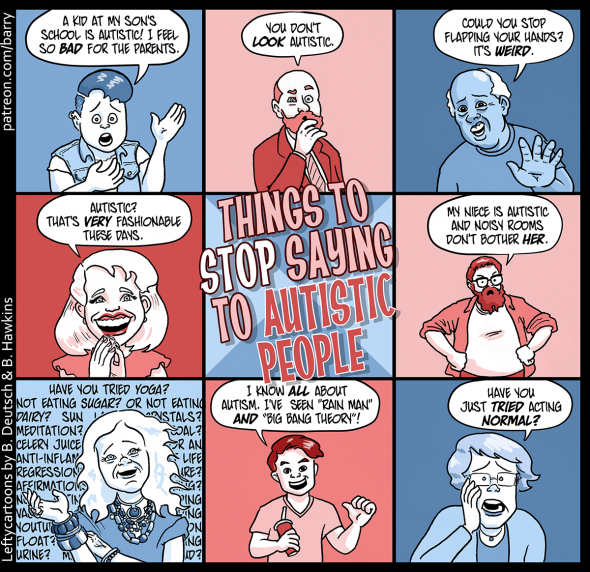

This cartoon has nine panels, arranged in a 3×3 grid. The central panel has nothing in it but large, cheerful letters, which say:

THINGS TO STOP SAYING TO AUTISTIC PEOPLE

Each panel features a different character speaking directly to the reader.

PANEL 1

A young person with a jeans vest over a white shirt with torn short sleeves – essentially looking like a modern person who for some reason is dressing like a 50s greaser – is speaking to the reader with a wide-eyed, sincere expression, one palm held up.

GREASER: A kid at my son’s school is autistic! I feel so BAD for the parents.

PANEL 2

A middle-aged man wearing a suit and tie, with a beard that screams “I am an intellectual,” is looking a little puzzled, one hand stroking his beard.

MAN: You don’t LOOK autistic.

PANEL 3

A balding man with white hair is holding out a hand in a “please stop that” gesture.

MAN: Could you stop flapping your hands? It’s weird.

PANEL 4

A woman with carefully-messy-styled hair and wearing a full makeup job is holding her hands with their palms against each other in front of her chin. She’s smiling very large.

WOMAN: Autistic? That’s VERY fashionable these days.

PANEL 5

This is the central panel, which has nothing in it but a caption, in large, cheerful letters.

CAPTION: THINGS TO STOP SAYING TO AUTISTIC PEOPLE

PANEL 6

A man with an enormous beard, and nice glasses, glares suspiciously at the reader, with arms akimbo.

MAN: My niece is autistic and noisy rooms don’t bother HER.

PANEL 7

A middle-aged woman with a somewhat hippy-ish vibe is smiling and talking to the viewer. She has fluffed-out white or blonde hair, and is wearing at least three rings, six bracelets, and four necklaces, nearly all of which are large and chunky. She’s speaking so much that it forms a wall of words behind her, most of which we can’t make out because she’s in the way, but we can read enough to get the gist of it.

WOMAN: Have you tried yoga? Not eating sugar? Not eating dairy? Sun… celery juice? …matory diet? … Acupunct…. Quitting sm…. Float?

PANEL 8

A young guy carrying a drink with a straw is grinning and pointing to himself proudly with a thumb.

GUY: I know ALL about autism. I’ve seen “Rain Man” AND “Big Bang Theory”!

PANEL 9

A middle aged woman leans forward towards us, a concerned expression on her face. She‘s dressed nicely in a jacket over a blouse and a simple necklace. She’s got one hand aside her mouth, as if she’s whispering to us.

WOMAN: Have you just TRIED acting NORMAL?

if i look autistic depends on if having headphones in most of the time and always having an elastomeric respirator on inside make me look autistic. certain sounds bother me but not all noisy rooms. bottom left is so shit

One thing not to say to neurodiverse people: “You must be on the autistic spectrum.” There are other spectra out there, not yet named, and I’m sick of blowhards calling me what I’m not. But as usual your cartoons rule.

That’s sounds SUPER annoying.

And thank you! I’m glad you’re enjoying the cartoons.

I was surprised when the profession decided that “a spectrum” was a good way to model neurodiversity. It seemed obvious that there were too many distinct modes of thinking for them to ever described by a one-dimensional analogy, and I can only understand it as a reaction against the similarly artificial way of denying commonality by describing some people as autistic, others as hyperactive, and yet others as having Asperger’s syndrome. I hope we move out of the current phase of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis dialectic because “the spectrum” doesn’t really explain anything.

The early binary model (“you’re X or you’re not X”) was harmful in more ways than denying commonality – it also denied a lot of people any recognition of their own phenotype, because if you didn’t meet a clearly defined set of criteria, you were classed as neurotypical. And if you happened to meet whatever arbitrary set of criteria were set for a particular condition – or more accurately, if you happened to meet the interpretation of those criteria by the person diagnosing you – then you were attributed a commonality with everyone else in the same group regardless of whether that was true (i.e., all “autistic” people were assumed to have trouble with basic communication, regardless of whether that was true).

The “spectrum” model is far from perfect, but it was a massive improvement from what came before it. Especially when used responsibly by healthcare professionals.

The problem is A – many healthcare professionals don’t use it responsibly (which is bad but is really an issue with training and screening of healthcare people, not the model), B – once the model is taken out of the domain of healthcare and becomes part of general cultural discourse, it becomes a set of streotypes that are liberally misapplid, just as any other model does, and C – *any* diagnostic model of human behaviour and mental states is oversimplistic and non-explanatory. Which is partially the point – the goal of creating these models is to simplify and reduce behaviour into categories, because we live in a society where most people aren’t offered bespoke treatment, and society has decided that it’s best to imperfectly help more people than perfectly help a selective few. But it’s a problem when people forget that it’s oversimplified, and treat it as some sort of natural reality.

I can present you a checklist of mental health conditions I have been diagnosed with, and a checklist of ones that have been ruled out, and a checklist of ones that I never was evaluated for. Those lists are helpful for some purposes – for example, determining which medications I need in order to live a relatively happy life and not suffer panic attacks. They’re also harmful for some purposes, because they make people make a lot of assumptions about me, some of which are very annoying. But personally, I’d rather people keep saying stupid, annoying things to me than have to go through another panic attack. And until someone figures out a better way to create a diagnostic system that works in a world with 8 billion people who all have needs, I think we shouldn’t be too dismissive of the current models. We should remain crticial of them, sure. And be especially critical of their misuse, absolutely. And keep on the pressure to do better. But not forget that the “spectrum” model, as crappy as it may be, is still by far the best model we have. And at the same time, remember that it’s just a model, and that’s all it’s meant to be.