════ ⋆★⋆ ════

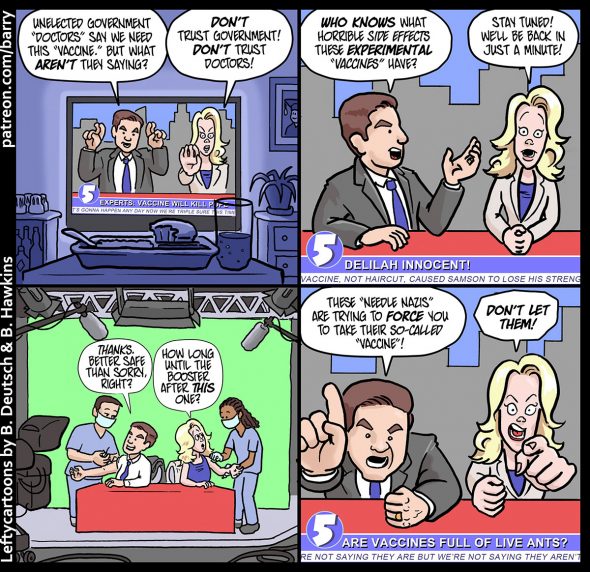

This cartoon is a collaboration with Becky Hawkins.

════ ⋆★⋆ ════

The vast majority of employees at Fox Corporation, the umbrella company for the conservative Fox News channel, are vaccinated against coronavirus and those who are not will be required to do daily testing, according to a memo sent out from bosses – despite some of its biggest screen stars questioning the vaccine.

════ ⋆★⋆ ════

I think I wrote this cartoon about a year ago. But Fox’s disdain and deception of its audience has been in the news again this month (which is February 2023 as I write this).

The most prominent stars and highest-ranking executives at Fox News privately ridiculed claims of election fraud in the 2020 election, despite the right-wing channel allowing lies about the presidential contest to be promoted on its air, damning messages contained in a Thursday court filing revealed.

It’s become clear that Fox is afraid they’ll lose their audience if they don’t lie to them. Which is another reason that for-profit news may not be a great idea. If a primary goal is profit, and lying is necessary to maintain profits, then why wouldn’t a news station lie to its audience?

And the more they lie – the more that their audience grows to expect comforting lies – the less able FOX is to stop lying. Reporting the news isn’t their goal; not losing their audience to Newsmax is their goal.

But as bad as market-driven news is, government-dominated news can be even worse – just look at how the news works in Putin’s Russia, or in Viktor Orban’s Hungary. This may be one of those “all systems can be terrible” situations.

Do you have a news site that you think is fair and reliable? Feel free to post what it is in the comments.

════ ⋆★⋆ ════

Becky: “My soundtrack for drawing this one was the audiobook Bellwether, by Connie Willis (which is a fun time!) and the first couple hours of Empire of Pain: the Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty (which is not fun, but is interesting so far!).”

Barry: Wow, isn’t the art beautiful? I especially love panel one, with the details of the dimmed room surrounding the TV.

════ ⋆★⋆ ════

TRANSCRIPT OF CARTOON

This cartoon has four panels. All four panels show the anchors of a conservative news show, a man and a woman, both of whom are well-dressed and have very carefully styled hair. They’re sitting at a news desk and talking to the camera, with a backdrop of a cityscape behind them. A chyron (text) runs across the bottom of the screen.

PANEL 1

We’re in a darkened living room. We can see a TV dinner, partly eaten, on a tray in the foreground; in the background is a TV, surrounded by a liquor cabinet on the left and a houseplant on a chest of drawers on the right. The TV is turned on, providing the only bright colors in the panel. The male anchor is making air quotes with his fingers, while the female anchor is holding out her hand in a “stop!” gesture.

MAN: Unelected government “doctors” say we need this “vaccine.” but what aren’t they saying?

WOMAN: Don’t trust government! Don’t trust doctors!

PANEL 2

We are now seeing just what’s on the TV screen. The male anchor has turned towards the female anchor and is speaking to her, one hand waving in a sort of “angry questioning” motion. The female anchor has folded her hands on the desk in front of her and is speaking directly to the camera.

MAN: Who knows what horrible side effects these experimental “vaccines” have?

WOMAN: Stay tuned! We’ll be back in just a minute!

PANEL 3

Our vantage point has pulled back. We’re now obviously in a TV studio; we can see cameras and microphones pointing at the two anchors, and the slightly-raised platform the anchor desk sits on. There’s a large bright green screen behind them, instead of a cityscape.

Two people in nurse’s scrubs, both wearing face masks, have come up to the desk. Both anchors have taken their jackets off, and he’s rolled up a sleeve (her blouse is sleeveless). The nurses are injecting medicine into their arms.

The male anchor is smiling cheerfully, while the female anchor speaks to her nurse with a concerned expression.

MAN: Thanks. Better safe than sorry, right?

WOMAN: How long until the booster after this one?

PANEL 4

We’re once again looking at them as they appear on a TV screen; the cityscape backdrop is back. They’re both looking angry and gesturing towards the screen with extreme foreshortening; he’s holding a finger up near the screen, and she’s pointing straight at the screen like Uncle Sam.

MAN: These “needle Nazis” are trying to force you to take their so-called “vaccine”!

WOMAN: DON’T LET THEM!

CHYRONS

What the chyrons (the crawl of text across the bottom of the TV screen) say. (The second line of each chyron is cut off on one or both sides of the screen, to simulate the words scrolling across the screen.)

Panel 1: EXPERTS: VACCINE WILL KILL POPE

…t’s gonna happen any day now we’re triple sure this time…

Panel 2: DELILAH INNOCENT!

…vaccine, not haircut, caused Samson to lose his streng…

There’s no Chyron in panel 3.

Panel 4: ARE VACCINES FULL OF LIVE ANTS?

…re not saying they are but we’re not saying they aren’t…

════ ⋆★⋆ ════

Yeah, the utter obsession with trans people by the Right -- I'm not sure what it means, but it's pretty…