This is a guest post by Carla, which originally appeared on her blog Writing in Water, and appears here with her kind permission.

A favourite tactic of critics of sexual violence surveys is to claim they inflate their results by wording questions too broadly. Three surveys in particular have attracted their attention: Mary Koss’s 1987 survey of college students, NIJ’s 2007 Campus Sexual Assault Survey (CSA) and the CDC’s 2011 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS). The first of these, Koss’s survey—the original source of the “one in four” statistic—is now almost thirty years old, but it still looms large in the minds of rape truthers, who continue to try to debunk it. More recently, the White House’s focus on violence against women has drawn attention to CSA and NISVS. These surveys are the source of the White House’s claims that one in five women will be sexually assaulted while in college and that nearly one in five women will be victims of attempted or completed rape respectively.

Since critics of these surveys have mostly concentrated on questions asking about incapacitated rape or sexual assault, a prefatory note is in order. Rapists unsurprisingly favour the most vulnerable victims they can find. A woman incapacitated by drugs or alcohol—that is, a woman who is unable to resist—is a vulnerable target for a rapist. (This is in no way to blame women who drink to excess; rapists who target incapacitated women are as responsible for their crimes as those who use physical force.) In environments where drugs and binge drinking are common, such as on university campuses, it is not just unsurprising that a high proportion of rapes would involve incapacitation: we should expect that this would be the case.

MARY KOSS

Mary Koss’s seminal survey of experiences of sexual violence among female college students revealed shockingly high rates of sexual assault—12.1% disclosed being raped since the age of 14 and a further 15.4% disclosed being victims of attempted (but not completed) rape. Koss’s research was groundbreaking in the way it lifted the veil on acquaintance and date rape, which until then were not part of the national lexicon. In addition, her rigorous approach, with its detailed, explicit questions, revolutionised the way in which surveys of sexual assault are designed. Almost thirty years after it was first published, its validity has never (whatever Wikipedia says) been challenged by researchers in the field of sexual violence.

Koss’s research soon attracted negative attention in the media. One of the most persistent criticisms of her research has been the claim, originating in a 1992 essay in the journal Society, ((Gilbert, N (1992), ‘Realities and Mythologies of Rape,’ Society 29.4: 4-10.)) that the incapacitation question captured events that were not rape. This focus on the incapacitation question is misleading, because removing it from the survey does not alter the results substantially—the number of women disclosing rape or attempted rape falls from one in five to one in four. Nonetheless, criticism of these questions has helped convince many that Koss’s estimates of sexual violence prevalence are wildly inflated.

For reference, the question that Koss asked her respondents was:

Have you had sexual intercourse when you didn’t want to because a man gave you alcohol or drugs?

The mention of drugs or alcohol given “by a man” may seem odd, but it was worded this way because it was designed to mirror Ohio law which, like many other jurisdictions at the time, only recognised incapacitated rape when the drugs or alcohol were administered by the rapist. (Since Koss did not ask about events where the victim drank or took drugs of her own accord, this is a highly conservative definition of incapacitated rape.) According to the Society essay, “as [it] stands it would require a mind reader to detect whether an affirmative response” to this question “corresponds to a legal definition of rape.” For example, “[i]t could mean that a woman was trading sex for drugs or that a few drinks lowered the respondent’s inhibitions and she consented to an act she later regretted.” We might think about what it means for someone to be sceptical about the scale of sexual assault uncovered by Koss’s survey while simultaneously believing that her numbers can be accounted for by women prostituting themselves for drugs or being unable to tell (or lying about) if they actually consented to an act or not.

However, we don’t need to guess if Koss’s survey participants were able to interpret the question correctly. Her rigorous testing of her survey questions (called the Sexual Experiences Survey, or SES) was one of the reasons why her research was so groundbreaking. None of Koss’s critics has found fault with the methods she used to test the reliability of her questions; the most they have been able to do is to imply—in an utterly unwarranted attack on her professional integrity—that she might be misleading the public about including the incapacitation questions in her testing (they were). ((Gilbert 1992.)) At any rate, any question about the reliability of Koss’s questions should have been put to rest by the fact that more recent surveys using more explicit questions to ask about incapacitated rape have consistently yielded comparable results to her 1987 survey.

CSA

CSA surveyed over 5000 undergraduate women at two large universities. 28.5% of the participants disclosed experiencing attempted or completed sexual assault in their lifetimes and 19.8% of seniors disclosed experiencing completed sexual assault since entering college. ((This sentence has been corrected. Originally it said “19.8% of seniors experienced attempted and completed sexual assault while at college,” but it should have said “completed assaults” only.)) | ((An addendum from Carla: [CSA researcher] “Chris Krebs also told me that when you take out sexual battery (that is, you only measure completed rapes) the number falls from 1 in 5 to 1 in 7.”)) Because CSA focuses on sexual assault, a figure for lifetime prevalence of rape isn’t given, although 3.4% of all respondents (that is, not just seniors) disclosed being victims of completed physically forced rape and 8.5% disclosed being victims of completed incapacitated rape since entering college (note that these figures are not mutually exclusive).

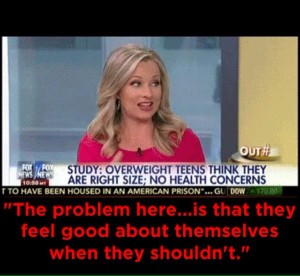

Taking their cue from criticisms of Koss’s research, critics of CSA have claimed the question about incapacitated sexual assault is so broad it captures all sexual encounters under the influence of alcohol. For example, an article in USA Today described the incapacitation question as including any “sexual encounters while intoxicated,” while one in the National Review characterised it as “broad and ambiguous” and “includ[ing] questions about sexual contact that occurred in cases where someone was ‘drunk,’ not only in cases where the person was ‘incapacitated.’” According to another critic, “What might be dismissed as a foolish drunken hookup is now felony rape.” One critic goes even futher, claiming that not only does the incapacitation question capture people who are “just drunk enough to go along with something he or she wouldn’t do when sober,” but that the questions asking about physically forced sexual assault are “worded so ambiguously that they could refer to a clumsy attempt to initiate sex, even if the ‘attacker’ stops once rebuffed.”

Most critics avoid quoting the actual question on incapacitated sexual assault. Its wording is in fact very explicit. The question is in two parts. First, respondents were asked:

Has someone had sexual contact with you when you were unable to provide consent or stop was happening because you were passed out, drugged, drunk, incapacitated or asleep?

Positive responses to this question then prompted the respondent to be asked if the “sexual contact” included:

*Forced touching of a sexual nature

*Oral sex

*Sexual intercourse

*Anal sex

*Sexual penetration with a finger or other object.

This question plainly does not ask about any and all sexual encounters where the respondent was intoxicated. It asks about sexual contact that occurred when respondents had been drinking so much that they could not consent or stop what was happening. In other words, it captures people who were incapacitated. It strains credulity that a reasonable person would interpret this as including consensual drunken sexual encounters, particularly given its context in a survey explicitly asking about unwanted sexual activity and its position immediately after a question on physically forced sexual contact.

The question about physically forced sexual contact, incidentally, begins with the following preamble:

The questions below ask about unwanted sexual contact that involved force or threats of force against you. Force could include someone holding you down with his or her body weight, pinning your arms, hitting or kicking you, or using or threatening to use a weapon against you.

Respondents were then asked:

Has anyone had sexual contact with you by using physical force or threatening to physically harm you?

And:

Has anyone attempted but not succeeded in having sexual contact with you by using or threatening to use physical force against you?

Finally, they were asked the questions listed above describing specific sexual acts.

The idea that this question is “worded so ambiguously that they could refer to a clumsy attempt to initiate sex, even if the ‘attacker’ stops once rebuffed” is baffling. Perhaps for some a crisis of inept men whose attempts at seduction cannot be distinguished from attempted physically forced rape is more plausible than a crisis of sexual assault of young women.

NISVS

Unlike the previous two surveys, which focused on college students, NISVS surveyed women in the general non-institutionalised population. It had a sample size of almost 10,000 randomly selected women, of whom 18.3% disclosed completed or attempted rape over the course of their lifetime. Broken down further, 12.2% reported completed forced penetration, 5.2% reported attempted forced penetration and 8.0% reported incapacitated rape (note that these categories are not mutually exclusive).

NISVS has attracted less attention than the other two surveys. Many critics of it (see, for example, here, here and here) actually seem to be unaware that it is an entirely different survey from CSA. Most other critiques of NISVS rely on a 2012 Washington Post article in which it is claimed the survey defines sexual violence in “impossibly elastic ways” and, more specifically, that the question about incapacitated rape includes all “sex while inebriated.”

The actual wording of the incapacitation question in NISVS is slightly different from CSA. First, the respondents were read the following preamble:

Sometimes sex happens when a person is unable to consent to it or stop it from happening because they were drunk, high, drugged, or passed out from alcohol, drugs, or medications. This can include times when they voluntarily consumed alcohol or drugs or they were given drugs or alcohol without their knowledge or consent. Please remember that even if someone uses alcohol or drugs, what happens to them is not their fault.

They were then asked:

When you were drunk, high, drugged, or passed out and unable to consent, how many people have ever had [vaginal sex etc. with you]?

Significantly, the Washington Post article quotes only the second part of the question; the implicit claim is that the question could be interpreted as asking about four separate scenarios that include being 1) drunk 2) high 3) drugged and 4) passed out and unable to consent. But this is obviously not how the question is supposed to be interpreted. As this blogger points out, the preamble makes it clear that the phrase “unable to consent” is supposed to modify all four of the adjectives “drunk,” “high,” “drugged” and “passed out.” What’s more, as with Koss’s survey, we know this is how respondents were likely to interpret it because, like all the questions in NISVS, it underwent cognitive testing to ensure it was interpreted correctly. It’s simply fanciful to suggest that the (admittedly shocking) rates of rape revealed by this survey are the result of misunderstanding of the incapacitation question. After all, anyone determined and creative enough can find alternative interpretations for almost any question, but that doesn’t mean people actually taking the survey are likely to do so—otherwise we might as well give up administering surveys altogether.

Of course, no survey is perfect and getting people to disclose sensitive events like sexual assault is particularly challenging (although perhaps not for the reasons that critics of sexual violence surveys imagine). Questions should be, and are, tested, refined and improved. It’s distressing, however, that people with no expertise in sexual assault research are given public forums to make baseless claims about the methodology of these surveys. Yes: it’s shocking to learn that sexual violence is experienced by so many women. It may defy our personal sense of what is reasonable or believable. But it is precisely these preconceptions—our desire to believe that the world is a certain way—that should force us to be critical, especially when confronted with laypeople purporting to debunk established, peer reviewed research.

@beth: Thank you