Dear Helen,

Hi! I’m writing to respond to your open letter, “on Fat Scholarship and Activism.”

A thousand words seems cruelly scant to me, but I’ll do my best.

For space reasons, I won’t dig into our “obesity vs fat” semantic disagreement. I suggest we each use our preferred word, neither making a fuss about the other’s choice. (Ditto for “fat acceptance” vs “fat activism.”)

Part 1: Your charges against the fat acceptance movement.

Your criticisms of fat acceptance are a mix of cherry-picked examples and uncharitable readings.

For instance, you say where fat activism “could oppose discrimination against obese people in the workplace, it goes on about ‘romantic discrimination.’” But the linked article contains only three paragraphs about “romantic discrimination,” a fraction of a much longer piece. (And do you really think cultural components of attraction aren’t worthy of being written about? I can’t agree.)

Your claim that fat acceptance “doesn’t do this kind of work” – meaning opposing things like workplace and medical discrimination – is staggeringly wrong. I could provide a hundred links of scholars and activists addressing those issues, but since time is limited, hopefully just ten will prove my point.

Your other indictments followed a similar pattern, but with only 1000 words, I must move on!

(This article by Angie Manfredi, aimed at teens, is a non-comprehensive but accurate overview of fat acceptance’s goals. And Yasmin Harker created this useful bibliography of academic works about fat rights and fat discrimination.)

Part 2: Why I’m Generally Anti-Diet

We both want to end stigma and discrimination against fat people. Where we disagree (if I’ve understood correctly) is that you think fat people should try to not be fat, and that fat people are by definition unhealthy.

Accepting for a moment, for argument’s sake, that fat is unhealthy, that doesn’t necessarily lead to the conclusion that most fat people should try not to be fat.

First, I’ll stress that no one is under any obligation to maximize health. Exercise and cooking can take time, space, money, and mental energy which not everyone has. And people can legitimately prioritize other things.

But some fat people do wish to prioritize their health. Shouldn’t those fat people be encouraged to lose weight?

Some should – people with specific, serious conditions that weight loss could help (even if they’d still be fat).

But for 99% of fat people, I’d say not. The evidence is clear that weight-loss plans don’t work for the large majority. Most never lose a significant amount of weight – certainly not enough for a fat person to stop being fat. And usually whatever weight is lost – or more – comes back within five years. This causes mental anguish, because failure to lose weight, or to maintain weight loss, easily turns into self-hatred. If the person tries multiple times (as is common), the physical effects of yo-yo dieting can be very harmful.

Wayne Miller, an exercise science specialist at George Washington University, wrote:

There isn’t even one peer-reviewed controlled clinical study of any intentional weight-loss diet that proves that people can be successful at long-term significant weight loss. No commercial program, clinical program, or research model has been able to demonstrate significant long-term weight loss for more than a small fraction of the participants. Given the potential dangers of weight cycling and repeated failure, it is unscientific and unethical to support the continued use of dieting as an intervention for obesity.

Am I saying fat people who want to be healthier should give up? Absolutely not. I’m saying becoming healthier doesn’t require futile attempts to lose weight.

Please look at this graph. (Source.) It shows likelihood of mortality as it relates to weight and four other characteristics: fruit and vegetable intake, tobacco use, exercise, and alcohol. These are sometimes called the “healthy habits.”

On the left side of the graph, fat people who practice no “healthy habits” – smoking, no veggies, immoderate drinking, no exercise – have a much higher mortality risk than so-called “normal” weight people with unhealthy habits (although the “normals” have elevated risk too).

On the right end of the graph, fat people who practice all four healthy habits have a mortality risk that’s just barely higher than their thinner counterparts. More importantly, we can see that fat people who practice all four healthy habits benefit enormously, compared to fat people who don’t. (“Normals” benefit enormously from these healthy habits, too.)

Most fat people can’t permanently lose enough weight to stop being fat. But most fat people can eat more veggies, can not smoke, can limit ourselves to one glass of hootch a day, can add moderate exercise to our lives. These things aren’t always easy, but they are all much more achievable, for most fat people, than stopping being fat.

Achievable advice is better than unachievable advice. There’s a positive way forward for most fat people who want to be healthier – one that’s more likely to work, and less likely to encourage self-hatred, than trying to stop being fat.

One final thought: stigma against being fat may be more harmful than fat itself.

These findings suggest the possibility that the stigma associated with being overweight is more harmful than actually being overweight… Growing evidence suggests that weight bias does not work; it leads to greater morbidity and, now, greater mortality.

(See also.)

Could we get rid of weight bias while still holding the belief that fat people must lose weight? I doubt it. Reducing stigma could do more for fat people’s health than reducing waistlines.

There’s so much more to say (harms of dieting; benefits of a Health At Every Size approach; how HAES can help with disordered eating; etc), but I’m out of space.

I hope this letter finds you happy, well, and socially distanced someplace very cozy.

Best wishes, Barry

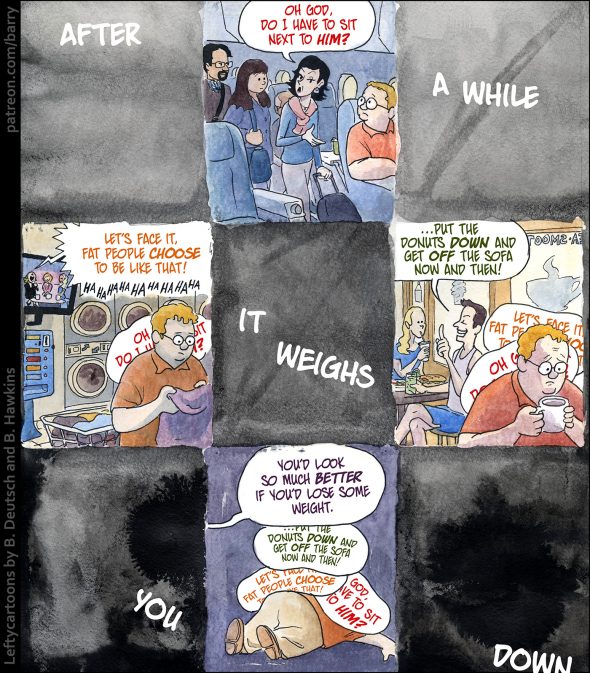

Or did the artist simply do what comic strip artists have taken the liberty of doing for decades --- which…