[Warning: This post contains descriptions of, and discussion of, rape.]

In comments, a new comment-writer named “Ben” presented “three very strong objections to the California affirmative consent law.” Before I respond to Ben in a future post, I want to make it clear what Affirmative Consent laws do, and what problem they are intended to address.

I don’t think that this law is going to, by itself, create huge changes. “Affirmative Consent” laws – also called “yes means yes laws” – aren’t revolutionary; they’re a fairly minor change to existing laws, which have been moving in the direction of being consent-based for many years.

I’m not expecting California’s Affirmative Consent law to bring a big upswing in colleges punishing rapists, and I’m not expecting a huge drop in rape prevalence on California campuses. Rape prevalence has many factors, and no piece of legislation can create huge change. Changing the law is an important step, but it is only one step, not a whole marathon.

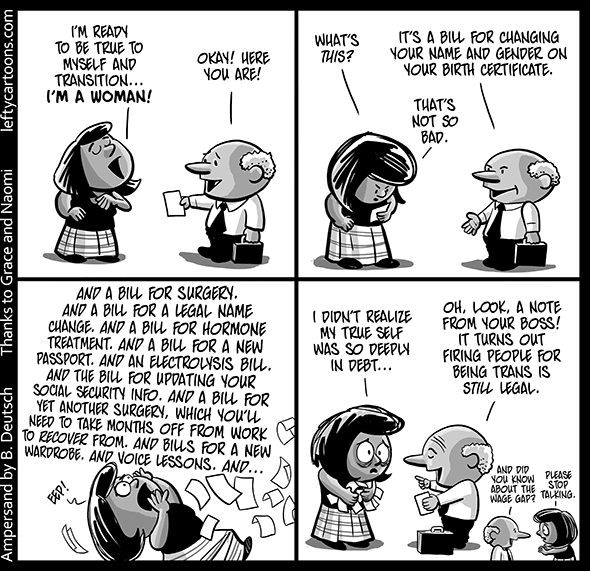

Let’s get a few common misconceptions out of the way, while we’re at it: The law is gender-neutral, at least in language (whether some of the people applying it will be sexist is another matter). ((Actually, let me just say straight out: Some of the people applying the law will be sexist, just as some people applying the previous law were sexist. This includes some college administrators who aren’t concerned enough with protecting accused male students’ rights, and who aren’t willing to recognize rape of male students as a problem. This is a serious problem – but the solution is to address the sexism, not to oppose Affirmative Consent. Repealing this law won’t make the sexism go away.)) The law doesn’t require explicit verbal permission at every stage of activity. The law does not say that men are automatically guilty if accused.

So what does Calfornia’s Affirmative Consent law say? The whole text is here, but I think this is the most important bit (emphasis mine):

“Affirmative consent” means affirmative, conscious, and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity. It is the responsibility of each person involved in the sexual activity to ensure that he or she has the affirmative consent of the other or others to engage in the sexual activity. Lack of protest or resistance does not mean consent, nor does silence mean consent. Affirmative consent must be ongoing throughout a sexual activity and can be revoked at any time. The existence of a dating relationship between the persons involved, or the fact of past sexual relations between them, should never by itself be assumed to be an indicator of consent.

So what kind of case could this law apply to? Consider Lisa Sendrow’s rape, ((Lisa Sendrow has chosen to publicly discuss her rape under her own name, in order to better help other rape victims. More information here.)) which George Will discussed – or, really, dismissed – in the Washington Post in June:

Consider the supposed campus epidemic of rape, a.k.a. “sexual assault.” Herewith, a Philadelphia magazine report about Swarthmore College, where in 2013 a student “was in her room with a guy with whom she’d been hooking up for three months”:

“They’d now decided — mutually, she thought — just to be friends. When he ended up falling asleep on her bed, she changed into pajamas and climbed in next to him. Soon, he was putting his arm around her and taking off her clothes. ‘I basically said, “No, I don’t want to have sex with you.” And then he said, “OK, that’s fine” and stopped. . . . And then he started again a few minutes later, taking off my panties, taking off his boxers. I just kind of laid there and didn’t do anything — I had already said no. I was just tired and wanted to go to bed. I let him finish. I pulled my panties back on and went to sleep.’”

Six weeks later, the woman reported that she had been raped. Now the Obama administration is riding to the rescue of “sexual assault” victims.

Will thinks it’s ridiculous to call this “rape” – so ridiculous that he doesn’t even need to explain why. But we can guess that her lack of resistance, and the fact that she had voluntarily had sex with this guy in the past, figured into Will’s analysis.

Although Will’s column was controversial, many agreed with it. For example, Cathy Young, a national columnist who often writes about rape issues, tweeted:

She said no, the guy (her former steady hookup) made another move a few minutes later, she went along with it. Apparently b/c she was “tired” or something like that. Sorry, calling this rape is insulting to real victims.

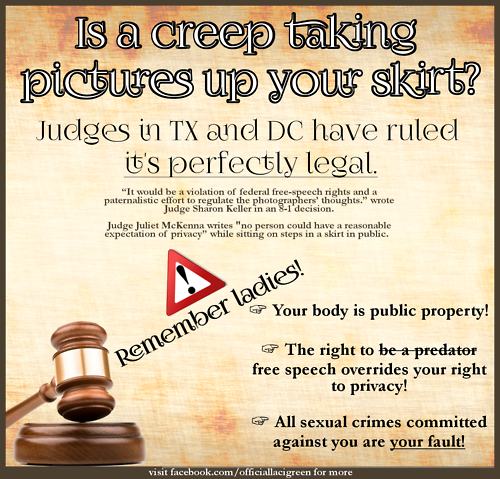

Cathy is explicit – he was “her former steady hookup,” and Lisa “went along with it” (lack of resistance), therefore it wasn’t rape. Never mind that Lisa said “no” – in the minds of Cathy, and George Will, and the millions of Americans with similar views, it’s not enough to say “no.” Lisa didn’t say no enough. Lisa didn’t resist enough. Lisa just lay there, and in many people’s minds that’s as good as consent right there.

Implicit in Cathy and Will’s analysis is that it should be legal to presume consent exists until all possibility of consent is eliminated beyond all doubt. But that belief would make a huge number of rapes – of sex without consent – legal. That’s not what any of us should want.

Lisa Sendrow did not consent, and has been very clear that she did not consent. What happened to Lisa Sendrow was rape, if sex without consent is rape. But many people believe it’s not rape if the victim “went along with it,” or if it’s a “former steady hookup,” or if she let him into her dorm room. And, unfortunately, many college administrators share Cathy and Will’s terrible views.

That is why this law is necessary. So that when someone with an experience like Lisa Sendrow’s goes to her college administration and says she or he was raped, she or he won’t be told it wasn’t rape because the rapist was a former hookup, or because she or he didn’t resist. Or, if she is told that, at least the law will be clearly on her side, not the college’s.

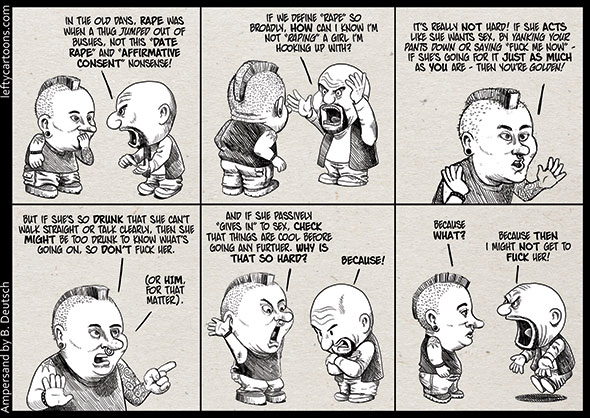

Lisa’s story isn’t uncommon. Boys in particular, in the United States, learn that the way to get consent is to wear girls down. This is a direct result of beliefs like George Will’s – the belief that pestering a girl or woman until she just gives up resisting can’t be rape. Mallery Ortberg gets at why this view is dangerous and encourages rape:

One of the dangers, I think, of depending on passive consent — the idea that all conditions are Go unless you are met with a swift, stern “NO MEANS NO” or a slap to the face — is that it conditions sexual aggressors (particularly men) to ignore or deflect or attempt to wear down perfectly clear rejections. As long as a No is plausibly deniable, it isn’t really a No; and if she didn’t really say No then you can’t possibly have done anything wrong.

In my very highly-rated, wealthy Connecticut high school – and in the pricey summer camps I went to during the summers – guys traded tips on getting laid. I know a lot of people hate this term, but a lot of what we told each other is best described as rape culture 101. One of the most popular strategies – at least, to talk about – was to take a girl for a drive and then pretend to run out of gas in some lonely spot. I’m not in high school any longer, but I would assume some guys still trade similar strategies today. What “strategies” like this teach boys is that the way to have sex is to put a girl in a situation in which she can be pestered until she finally stops saying “no” or resisting. I’m sure for most of us it was just talk; I’m also sure that a few did more than talk. This was not considered rape by any of us.

The TV show It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia captured this attitude perfectly:

Dennis: What do you mean, what do we need a mattress for? Why do you think we just spent all that money on a boat? The whole purpose of buying the boat in the first place was to get the ladies all nice and tipsy topside so we can take them to a nice comfortable place below deck, and, you know, they can’t refuse. Because of the implication.

Mac: Oh, uh, OK. You had me going there for the first part. The second half kind of threw me.

Dennis: Dude, dude, think about it. She’s out in the middle of nowhere with some dude she barely knows, she looks around, what does she see, nothing but open ocean. (Imitating female voice) “Oh, there’s nowhere for me to run. What am I going to do? Say no?”

Mac: OK. That seems really dark.

Dennis: Nah, it’s not dark. You’re misunderstanding me, bro.

Mac: I think I am.

Dennis: Yeah, you are. Because if the girl said no, the answer, obviously, is no. But the thing is she’s not gonna say no. She would never say no. Because of the implication.

Mac: Now, you’ve said that word “implication” a couple of times, what implication?

Dennis: The implication that things might go wrong for her if she refuses to sleep with me. You know, not that things are gonna go wrong for her, but she’s thinking that they will.

Mac: But it sounds like she doesn’t want to have sex with you.

Dennis: Why aren’t you understanding this?

This “implication” kind of rape – which is virtually never considered rape by the rapist – is commonplace. Find a vulnerable person, get her or him into a situation where it might be difficult to say “no,” and then persist until the victim becomes worn down and stops resisting. ((The cartoonist Uli Lust, in her in her autobiography, depicts herself as a young girl hitchhiking across Italy – and man after man rapes her using this strategy. As one especially blatant man told Uli, “We are far away from any village in the mountains. It is dark and cold outside, and it is raining. You can choose, either we have sex together, or you leave this house right now and sleep on the stones.”))

Sophia Katz, a young Canadian writer, wrote an essay describing how Stephen Tully Dierks, ((One of Dierks’ roommates has supported Sophia Katz’s account, and another woman has come forward with an account of being raped by Dierks almost identical to Katz’s. Dierks, it should be noted, didn’t deny Sophia’s story but said that he thought she had consented. Predictably, some people have criticized Sophia Katz’s actions and blamed her for her rape.)) an editor she had exchanged emails with, invited her to stay with him in New York City. It was her first visit to New York, and she didn’t know anyone there, and she didn’t have many resources. The first night she managed to fend Dierks off. The second night he wore her resistance down:

That evening we were in his room sitting on his bed, and he began kissing me again. I felt unsure of how to proceed. I had no interest in making out with him or having sex with him, but had a feeling that it would ‘turn into an ordeal’ if I rejected him. I had never been in a situation where I was living with someone for a period of time who wanted to have sex with me, that I didn’t want to have sex with. I knew I had nowhere else to stay, and if I upset him that I might be forced to leave. We continued kissing and I felt like vomiting. He took off my clothes and I felt like wrapping myself in one million layers of plastic. He seemed to be ‘preparing’ to have sex with me, and I imagined becoming invisible. Suddenly I heard the lock on the apartment door click, and all four of his roommates entered.

“Wait, Stan we can’t. Everyone just got home; they will definitely hear,” I said, hoping this was a way out.

“No they won’t. It’s fine. Let’s keep going.”

“No, I think they will. I really don’t want to if your roommates are home. We really shouldn’t.”

“No, it’s fine. We should. We should. Let’s keep going.”

“Stan, please can we just do this later. Your walls are really thin.” I felt tears welling up in my eyes and tried to dissolve them. I didn’t want to do it later. I didn’t want to do it ever. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I wanted to leave, but I was trapped with him in his tiny, dimly lit room.

“No, we should keep going. Let’s keep going.”

He got on top of me. I began to relinquish control.

Was that rape? I sure think so. Was it legally rape? It’s ambiguous. She said no, again and again – but then she stopped resisting.

This is an ambiguous area in the law, and arguably a loophole in our current sexual assault law, and in our cultural idea of what constitutes rape. If you can just get her or him to stop resisting, if you wear her or him down, then you can have sex without consent and pretend it isn’t rape.

Shutting that loophole is what Affirmative Consent is about. Shutting the loophole legally, and – as one among many steps – shutting it culturally. It is part of the larger “yes means yes” movement to make people understand that merely because someone doesn’t resist (or did resist, but stopped) doesn’t mean they’ve consented.

It’s also important to realize that many people – but especially young guys who don’t know much about sex – have absorbed the cultural (and legal) message that lack of resistance equals consent. As long as this attitude is prevalent, committing rape doesn’t require being as overtly venal as the character from “The Implication.” It merely means being able to lie to yourself a little in pursuit of sex; being willing to ignore the signs of fear or freezing up or displeasure because they haven’t actually said “no,” or they did say “no” but that was several minutes ago. The British psychiatrist Nina Burrowes, who studies and writes about sexual assault, describes in this video (start at 5:03) how many rapists genuinely don’t think of themselves as rapists or want to be rapists. For these cases, making it clear, legally and culturally, that lack of resistance isn’t consent could actually rescue some people from committing rape – a benefit for both them and their victims. ((I’m not saying this is the case for ALL rapists. I suspect some readers will respond as if I’ve said that all rapists just misunderstand what’s going on, and if we could only explain rape clearly they’d stop raping. Clearly that’s not the case. But if there are marginal rapists whose behavior could, in fact, be influenced by making it clear that lack of resistance doesn’t equal consent, then making that marginal change is a reasonable thing to do.))

Is the law perfect? No, of course not. No matter what the law says, many rapes will be unprosecutable. That’s just the way it is; not all crimes can be proven. But that’s true of any imaginable rape law, not something unique to Affirmative Consent.

My major objection to the California law is that it doesn’t provide enough protections to the accused student; for instance, she or he should have a protected right to have an advocate and adviser present at all hearings, the right to consult a lawyer, the right to have a representative question witnesses. She or he should, in short, have guarantees of due process. However, this means that California law should be amended to guarantee due process for accused students (all accused students, not just those accused of rape); it doesn’t mean that Affirmative Consent itself is a bad idea.

Okay, now that I’ve explained the need I think this law is addressing, in my next post I’ll actually reply to Ben.

Am I the only one who read "Beware the narcoterrorists" and thought "beware the jabberwock"?